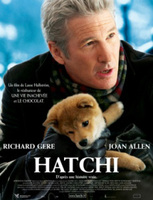

As the tale goes Akitas are one of the most loyal and loving breeds of dog in the world. You do not choose an Akita an Akita must choose you. Sent from a monastery in Japan an Akita puppy finds himself alone on a train station platform in America, when his shipping crate falls off the back of a trolley. There he chooses his companion for life, a University professor of music Parker Wilson (Richard Gere) who takes the dog home. Parker and the dog who he names Hachi (meaning number 8 in Japanese) strike up an unforgettable and lasting bond. Each day Hachi accompanies Parker to the station to catch his train and then returns later to meet him. When Parker tragically dies at work Hachi is left waiting and there he continues to wait without remedy for his grief, at the same place and time for the next ten years, which unfortunately is the rest of his life.

This heartbreaking story of love and devotion falls into the genre of the family film, although it is not a typical example. The director’s brave exploration of bereavement, somewhat worsened by the fact that it is the animal that grieves and suffers, means that it is not suitable for all families with young children[1]. It does however show the adorable Hachi growing up into adulthood, under the parental guidance of Parker and his wife (Joan Allen) and suggests that it is the animal within the family and community that makes it happier and stronger-elements of which are common in this type of film.

The story is also part melodrama and biopic, which means it isn’t just sad because of the heightened emotions melodramas evoke, or because of its over the top use of music[2], it’s extra sad because it’s based on true events. While biopics tend to be about people[3], there is something special about the fact it is the animal in this that has been put in the spotlight.

Despite starring the king of schmooze and schmaltz Richard Gere, Hachi A Dog’s Tale is not just another cheese fest about a man and his dog. It’s a great film about a dog and his man. From the opening scenes the importance of what Hachi ‘the animal’ wants is made the focus. When the little dog’s crate falls off the back of the trolley in the station, the audience sees him break out of his wooden cage[4]. He earns his freedom and right of choice in this act. From there the camera follows him from a floor level angle as he totters down the platform. We witness him looking different ways and changing direction once as though he is looking for something specific. He then passes a number of blurred feet (which represent the choices of companion he has) before finally a man’s voice becomes audible above the din of the crowd. Hachi upon hearing this sits down in front of a pair of feet as they stop and then he looks up to see Parker. It is Hachi’s adorable gaze therefore that introduces the human companion to the story, not the other way around. The reason why this is so effective is that it shows that Hachi has his own mind and right of choice. He knows what he wants and what he doesn’t. This means that when Hachi later grieves for his friend, his rights to these feelings and emotions are respected and understood. He is not presented at any point in the film as a dumb creature that doesn’t know what he is doing, or as a dog that doesn’t even realise his master isn’t coming back. He is elevated into a figure of intelligence and respect and is held up as a character, who perhaps understands more what it is to have loved and lost than his human counterparts.

Furthermore the way Hachi changes direction in this scene suggests that he is being guided by something other than his nose, a higher power perhaps. The producer of the film Vikki Wong makes an interesting comparison between Hachi waiting and a Monk Meditating[5], suggesting that there is something deep and spiritual going on with this character. The first time Hachi is introduced he is lifted out of a pen by a Japanese monk and is held up to the camera as though he is ‘the chosen one’. In this moment the film does seem to be saying that there is something a little bit special about Hachi, something that elevates him above the other characters in the film both human and animal- such as a cat in a book shop and a dog called ‘Lucky’, who approaches Hachi at the train station. Hachi’s interaction with Lucky the poodle is an interesting and ambiguous moment[6]. It cuts between Hachi’s perspective in black and white, a technique used throughout the film to situate the viewer in the animal’s mind, and then shows Hachi and Lucky in colour as they react to each other. The ambiguity in this scene comes out in the way Hachi and Lucky respond to this meeting. Lucky wags her tail and looks to communicate with Hachi, but he remains unmoved. It is in this instance that the film confirms that Hachi is more than just a dog and that his relationship with Parker was not just a bond between a dog and a man, but a relationship that eclipsed all else. On the other hand Lucky coming over to Hachi may represent a moment of animal to animal sympathy, which I think is the interpretation I prefer. It makes the emotion of Love and grief universal and does not limit it to the human world.

It is the shared communal experience of grief and love between animals and humans that makes this film so powerful, as well as the sense of animals in the community having the right of choice. The scene I think sums up everything occurs at the end of the film. In it Hachi has been waiting for ten years and Parker’s wife (Joan Allen) comes across him at the station. She runs dramatically over to him and gives him a hug and asks, ‘If it’s alright with you would you mind if I wait with you for the next train?’[7] Even though it’s unlikely that Hachi would ever be able to say no, the wording of the dialogue puts the power in Hachi’s paws.

More importantly it shows respect towards the animal and an understanding on the behalf of the human of why he is waiting. During this scene the camera cuts to showing a hot dog vendor looking sad, a train ticket seller walking up to the station window and again looking sad and more importantly in a performance well worthy of a Pawscar (the animal equivalent of the Oscars) Hachi is also shown to be sad. In fact the dog actor playing Hachi in this has been called ‘The Meryl Streep of the dog world!’ Another notable example of an animal given a right of choice appears early on in the film when a cat in a book shop hisses and lashes out at at Hachi when its companion asks it whether Hachi can stay. ‘What’d you think Antonia, a new roommate?’

Any analysis of this film would be complimented by a viewing of the Japanese original Hachiko Mongatari[8]. This film is more of a faithful adaptation of the actual story but it differs in the way it presents the character of Hachi. In the Japanese original for example the audience is never given an insight into what the dog sees or feels in an interior way, therefore he is never seen to be choose to do something. He is also always filmed from an exterior perspective and no stress is put on community grieving. Hachi in this film grieves alone to the extent that he is forced out onto the street and is treated horrendously by people who throw stones at him and send him away because he does not fit in with their family life. This film unlike its American remake also shows the birth of Hachi and does not suggest that he just turned up on a train station platform.

Another film with similar themes to Hachi A Dog’s Tale is ‘Greyfriars Bobby. Although aimed at a Disney audience this film also explores animal grief and loyalty and shows an animal through its dedication to a dead master making a community stronger. In addition it puts great emphasis on the freedom of the animal to make their own choices of who they spend their life with.

Suggested reading:

Mayumi Itoh, Hachi: The Truth of The Life and Legend

Other links: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtqRTQ3_YUQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hz9lKN3BIiQ (youtube video of people crying after watching the film)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQ8TuxoSZeo (A news feature about the significance of Hachi in Japan)

[1] https://www.commonsensemedia.org/movie-reviews/hachi-a-dogs-tale (film guide for parents with children)

[2] Tim Dirks, 1999, https://www.filmsite.org/melodramafilms.html

[3] Tim Dirks, 1999, https://www.filmsite.org/biopics.html

[4]Hachi a Dog’s Tale, Lasse Hallstrom (2009) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O1vuMhWvZUs (sequence described plays from 0.3.54 minutes in)

[5] https://www.vickiwongandhachi.com/4/previous/2.html (accessed 11/04/13)

[6] Hachi, 2009 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O1vuMhWvZUs (scene plays from 1.12.08 mins)

[7] Hachi (2009) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vYW3yQzV1c (approx 01.44 mins)

[8]