Feathers Amongst the Furs: The Revival of Power Dynamic in 102 Dalmatians

The visuals of the original 1961 animation and the 1996 live-action adaption have become iconic to those familiar with the story of 101 Dalmatians. The sea of black spots dispersed across endless white furs. The gangly, striking screen presence of the archetypal villain, Cruella De Vil. The forcible contrast between the two in the battle between good and evil.

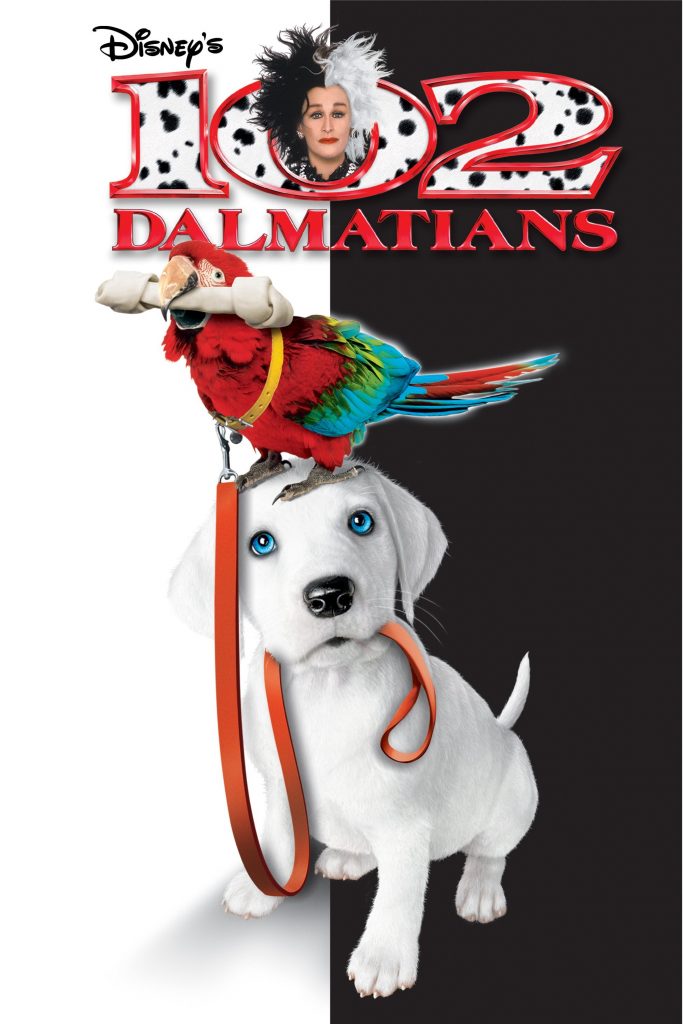

In Kevin Lima’s 2000 live-action sequel, a new cinematic function is brought into the power dynamic; Poncho the Parrot who believes that he is not only one of the dogs, but their chief protector. Throughout the film his comic value balances Cruella’s evil pursuits, providing humour alongside a more realistic villain to enhance action without darkening the tone too much within the Children’s genre. The following puppy rescue scene exemplifies how this is achieved stylistically.

The parrot’s position within the mise-en-scene is influenced by the stylistic portrayal of Cruella. Appearing centrally within the frame throughout the scene with his long, pointed, red silhouette, the macaw occupies space in a similar way. The immediate colour connotations create a visual representation of the character development that has been achieved thus far. Cruella and Poncho are confident individuals who perceive themselves to be all powerful and purposeful forces in the fate of the puppies; the bold and matching shade of red affirms these associations with strength and passion. The other characters, props and setting provide a contrasting colour palette of neutral tones which naturally falls as a background to the shocks of red, emphasising the power dynamic where Cruella and Poncho are strong and passionate amongst the more innocent and vulnerable masses.

The pair do not appear within the same shots, allowing one another to maintain their dominance on the screen. The actual size difference between Poncho and Cruella is not apparent to ridicule him, making his self-confidence seem more convincing to the audience.

It is not only the appearance of the parrot to others that empowers him, but the film maker’s creation of his own perspective; a playful adaptation to the conventional ‘bird’s-eye view’. At the start of the clip, a high-angle shot reveals the worker’s perspective as he catches a glimpse of the parrot sneaking in by glancing down towards the floor. This indicates the vulnerability of the rescuers in this setting. However, this switches to gradually empowering Poncho as the rescuers find the other puppies. As they find the puppies through the floor board, it is Poncho’s turn to have a high-angle shot from his perspective. This is a rare angle, however, as the positioning of parrot’s eyes on the sides of their faces contradicts the conventional human viewpoint in cinema. Lima tackles this by showing the shot from one eye. He then uses a zoom shot to expand a small vision to the whole frame, accrediting Poncho’s vision with finding the puppies.

Poncho is a refreshing addition to the good versus evil power dynamic that could have otherwise been exhausted through a sequel to such a well established narrative.