Sam Fuller’s final Hollywood film, White Dog (1982), is based on Romain Gary’s 1970 ‘nonfiction’ novel of the same name and tells the story of aspiring actress Julie Sawyer (Kristy McNichol), who after accidentally hitting and injuring him with her car, adopts a seemingly lovable white German shepherd. The plot is complicated when, after two gory incidents, Julie realises that her new companion is a ‘white dog,’ trained to attack and kill black people on site. The second half of the film depicts a black animal trainer’s (Paul Winfield) attempts to ‘reprogramme’ the dog and eradicate the racial prejudice that has been conditioned into his psyche. Paramount suppressed the distribution of White Dog in America following a pre-release consultation with the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), in which concerns were raised that the film communicated a racist message. This controversy led to Fuller essentially retiring from Hollywood and moving to France, and the film was not made fully available in America until 2008.

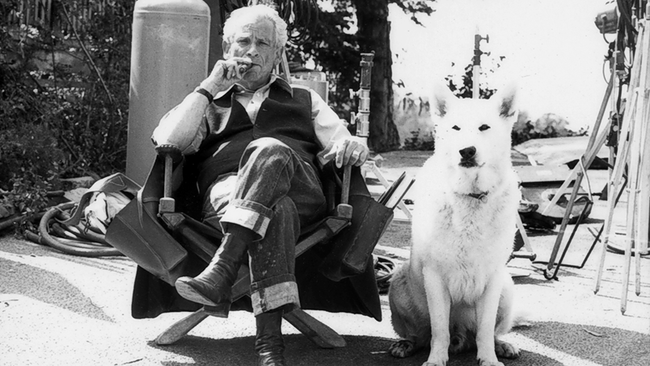

Romain Gary with his dog

While it certainly implements some of the characteristics of Fuller’s earlier Genre and B-Movie pictures, such as frequently sentimental or absurdly clichéd dialogue, to fully categorize White Dog as either would not do it justice. The film is a surprisingly nimble hybridization of drama and horror, with different aspects of exploitation film also feeding both facets of its genre. It can be viewed both as a hard-hitting, intrinsically metaphoric social commentary and as a terrifying depiction of malevolent animal agency. As such, the ‘white dog,’ who was played by five different German shepherds, functions both as a metaphor for socially conditioned racism and learned hate, and as the ‘nature-run-amok’ element of a horror film. Fuller combines the overtly antiracist didacticism of 70s blaxploitation films (a trend that had lost favour with the NAACP by the 1980s) with an animal focused narrative that exploits the cachet of successful animal horror films such as Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) and Spielberg’s Jaws (1975). The result is an enigmatic production, imbued with Fuller’s passion for animals, which allows its dual genres, for the most part, to compliment rather than obstruct each other.

Horror

Even without its allegorical element, White Dog could arguably function as a successful stand-alone horror film. Fuller seems intent on establishing an overarching horror-flick tone and on extracting as many scenes of violent excess out of his canine actors as possible. In the opening sequence at the vets, he chooses to accompany a close-up shot of the dog’s eyes as they open and focus on Julie with the introduction of Ennio Morricone’s ominous score, which immediately characterises the presence of the dog as mysterious and foreboding. This unnerving music is ever-present in the film, even at potential moments of light-heartedness or joy, which always limits their sentimentality. Horror film tropes are adopted throughout, from the early scene where the audience experiences a would-be rapist’s intrusion into Julie’s house from the point of view of the perpetrator as he skulks through the dimly lit hallway, to the highly stylized dog attack scenes. One such scene, where a black lorry driver is brutally attacked and murdered by the ‘white dog,’ is characteristic of horror as it is set at night and creates dramatic irony as the audience witness what Julie does not. As this scene begins, the lorry slowly comes to a halt and Fuller allows the silence to hang for a brief moment before it is punctured by sudden music and a frightening low-angle shot of the dog, teeth bared, white head silhouetted boldly against the dark night’s sky. This powerful image is followed by a sustained hand-held shot of the actual attack, capturing its viciousness and violent energy.

However, rather than actual physical threat, it is a fear of the unknown, and unknowable, that White Dog exploits. This is demonstrated in a much less frantic scene from earlier in the film when Julie’s friend Roland (James Parker) first encounters her new companion. A shot of his uneasy expression as he locks eyes with the dog is followed by another extreme close-up of the dog’s eyes, which widen uncannily. The unnerving tone of this scene is indicative of how the horror in the film functions; what the dog actually represents here is what Jacques Derrida termed ‘absolute alterity’ or ‘the absolute other.’[1] To Roland, the dog is an intrusive presence that he can neither fully understand or consequently control, as according to Derrida it is impossible to ever comprehend absolutely the ‘interiority’ of an animal. As such, the horror in White Dog pivots on the otherness of the dog itself, and on human fears of animal agency and our potential inability to exert control over it.

Racism

The social commentary of White Dog explores whether learned prejudices, specifically racism, can ever be unlearned and focuses on the efforts of Paul Winfield’s character, animal trainer Keys, to reprogramme the ‘white dog.’ Carruthers (Burl Ives), with his assertion that ‘can’t nobody can unlearn a dog, nobody,’ represents the attitude that racism, once it has a foothold, cannot be ‘cured.’ Keys represents the opposing view that conditioned hatred is reversible. The overarching metaphor of the film is actualised in one of the final scenes, when the dog’s original owners, a bigoted old man and his two granddaughters, come to collect him. Here, the two innocent children mirror the dog as they are subjected to the hateful, racist influence of their grandfather. Fuller constructs a powerful tableau here, in which a symmetrical image of this family is framed idyllically against the blue sky, demonstrating how hate and intolerance can perpetuate itself in outwardly innocent situations. The question of whether racism and hate can be unlearned is answered ambivalently in the closing scene. While Keys is successful in his endeavour to remove the dog’s’ compulsion to attack black skin, Fuller implements a final moment of horror that complicates the central metaphor of the film. As Julie embraces the dog after the successful experiment, the camera slowly pans 360 degrees, showing first the dog’s placid expression, then Julie’s relieved face, before returning to the dog, whose expression has transformed; he stares at Carruthers with his teeth bared as ominous brass music is reintroduced. The dog then attacks Carruthers, signifying that while racism can be unlearned, the deep-seated hatred that harbours such prejudice cannot, and will always perpetuate itself in some direction (Carruthers can be seen to embody, through physical likeness, the dog’s original owner). Finally, Keys is forced to end the life of the white dog.

Animals

There is a third attitude, however, towards the ‘white dog’, which is represented by the character of Julie, who believes that the dog is completely innocent of guilt and maintains this attitude until the final tragic scene. Julie’s dedication to the animal is one of many ways in which White Dog explores a difference in how racism, and ideology in general, is passed on from human to human, and from human to animal. Keys’ description of how a ‘white dog’ is trained through the hiring of a ‘black wino desperate for a drink,’ or a ‘black junkie desperate for a fix’ to physically abuse the animal until it associates black skin with pain and hate demonstrates how the dogs prejudice is learned through suffering. This contrasts with the way in which the transferral of racism in the human family is depicted in the scene where the original owners reappear. The scene in which the dog attacks a black man in a church is preceded by a sequence where a match cut links a low-angle tracking shot of the victim’s legs (he is wearing light trousers and dark shoes) with one of the dog’s, whose white legs contrast with his dirty paws. This visual connection subtly aligns the two characters through their victimhood. The dog’s depiction as a victim is furthered by the suggestion of duality in his personality. Julie calls him a name, ‘Mr. Hyde,’ only once, but this has deep significance, as she is suggesting that the racism in the dog is like a psychosis, and that the prejudiced has not altered what is, fundamentally, a good nature.

This subtle characterisation of the dog as a victim feeds into an underlying critique in White Dog about the treatment of animals and their indoctrination into human society. Fuller examines the consequences of the pet keeping industry, highlighting our fickle approach to adoption and the widespread practice of animal euthanasia. After learning that the injured dog is ‘too old to adopt, they only adopt cute little puppies,’ Julie visits the pound, where a man can be heard in the background asserting that a particular dog is ‘too big for the apartment.’ After we witness these rejections of animals based on age and size, an over-the-shoulder shot from Julie’s perspective reveals the blurred background scene of an unwanted dog being incinerated.

Some of the key imagery of the film is that of the cage. Fuller lingers on establishing shots of animals in cages, always in a state of agitation, and a large proportion of shots are focused through the bars of a cage. As such the representation of animals throughout White Dog is extremely unnatural and dominated by the fact of their relationship to humans. Even the benevolent Keys asserts his authority over animals and treats them as experiments: ‘to me, Noah’s Ark is like a laboratory that Darwin himself would go ape over.’ The naming of the training park as ‘Noah’s Ark’ is ironic given the scenes of animal discontent that Fuller captures within it. This sense of animals as the victim of human arrogance is reflected in Julie’s character, her affinity with the white dog, and the way in which her attitudes come into conflict with figures of authority and the established discourse about animals. When the veterinary assistant suggests that ‘if the owner doesn’t claim him in three days,’ the dog will be ‘put to sleep’, for example, Julie corrects her language, asking: ‘you mean they’d kill him?’ In this way, Julie is shown to challenge the discourse that is used by humans to distance themselves from the animal suffering that they cause.

Overall, White Dog depicts many of the negative consequences of human interaction with animals, from the routine dog euthanasia at the pound, to the sustained presence of caged and agitated animals at the training park. The individual circumstance of the corruption of the white dog’s psyche with evil human ideology comes to symbolise the corruption of animal freedom when humans privilege their own desires over the liberty of an animal. This idea is captured in a final bird’s-eye-view shot that focuses on the blood stains from Keys’ gunshots on the white dog’s fur. This powerful image demonstrates finally the corrupting power of humans upon animals.

At the heart of the film is the concept of otherness. It is the unknowable, uncontrollable otherness of the white dog that amplifies and deepens the superficial horror of the dog attacks. This otherness of animals is shown to be maintained by the established discourse that we use to discuss animals, and to distance ourselves from them in order to justify their maltreatment. It is perhaps by interweaving these ideas of otherness throughout his film, through animals, that Fuller can create such a powerful statement about the perpetuation of racism and hatred.

Fuller on set with

Viewing White Dog today, it is difficult to understand why its release was suppressed. Fuller directs a staunchly antiracist allegory that provides nuanced insights into the way in which humans treat each other, but also the way in which they treat animals. That the outcry at the film led to his retreat from Hollywood filmmaking is an unjust travesty. It is possible to see this film as an early blueprint for films such as Get Out (2017), which also combines the characteristic tone of a horror/thriller with a sobering social commentary on racism.

Further Reading

- Kujo (1983) dir. Lewis Teague – Stephen King adaptation released the year after White Dog, also features a dog as the central focus of horror

- The Crimson Kimono (1959) dir. Samuel Fuller – film-noir thriller in which Fuller deals with racial stereotypes

- Get Out (2017) dir. Jordan Peele – contemporary horror/thriller combined with commentary on racism Articles:

- Fuller, S. and Ranvaud, D. ‘An Interview with Sam Fuller’, The Journal of Cinema and Media, 19 (1982), pp. 26-8 – An interview with Fuller from around the time White Dog was released

- ‘The actress and the Black Panther: a story too good to check’, The Guardian (April 2002) https://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/04/24/1019441262517.html – article discussing the controversial death of Jean Seberg, the wife of Romain Gary and basis for the character of Julie Sawyer

- Coren, S. ‘Is It Possible That a Dog Could Be Racist?’, Psychology Today (Feb 2016)

https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/canine-corner/201602/is-it-possible-dog-could-be-racist – Psychology Today feature discussing learned prejudice in dogs

Bibliography

‘Buzz’, ‘Review: White Dog (1982)’, CampBlood (March 2010) http://campblood.org/Newblog/archives/2004

Derrida, Jacques, ‘The Animal that Therefore I am (More to Follow)’, Critical Inquiry, 28.2 (2002), 368-418

Hoberman, James, ‘White Dog: Sam Fuller Unmuzzled’, The Criterion Collection (November 2008)

IMDb, White Dog (1982) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0084899/

Schickel, Richard, ‘Interview with Sam Fuller (1990)’, Criterion

[1] Derrida, Jacques, ‘The Animal that Therefore I am (More to Follow)’, Critical Inquiry, 28.2 (2002), 368-418 (p. 380).