Having been lost for decades following its 1971 release, Wake in Fright was restored to considerable acclaim in 2009. Its aesthetic, screenplay and portrayal of the culture clash between outsiders and the aggressive ‘mateship’ mythology of Australia’s outback emerged fresher than ever. Wake in Fright follows English teacher John Grant, who is obliged to work in the outback for a year. On his way to Sydney for the holidays, he stops in the rural mining community of Bundanyabba, where he gambles his money away in a two-up game. Forced to remain in ‘the Yabba’, John mixes with the alcoholic locals, who take him on a drunken and brutal kangaroo-hunting trip. The violence doesn’t end there, as John’s night ends with Doc sexually assaulting him. A failed escape from the Yabba, and an equally unsuccessful suicide attempt, see John end the film where he started it – in his one-room schoolhouse in the outback.

In Images of Australia, Neil Rattigan identifies Wake in Fright as ‘a horror film, not within the traditional Hollywood genre this time, but in a uniquely Australian manner’. [1] Certainly, the film is intentionally unsettling, with Canadian director Ted Kotcheff’s refusal to shy away from the story’s brutal events often making for horrifying viewing. The use of setting, and other production tricks like reverse motion and the over-saturation of colour give the film an unrelenting distressful atmosphere, reaching its climax with the kangaroo hunt, which includes what Kotcheff called ‘documentary footage’ of genuine hunters killing kangaroos. [2] Indeed, many viewers (particularly in Australia) initially reacted angrily to the film, arguing that it portrayed Australians negatively. Jack Thompson, who plays Dick, recalls that people left the cinema saying ‘that’s not us’. [3] Of course, though it is inextricably linked to Australia by its location and blokey characters, the film was not produced to document a judgement of the country – besides, the expressionistic representation of John’s trials in this hellish world distract from any social commentary the film might make. Wake in Fright is, above all, a horror story about one man’s encounter with difficult people in a difficult place – and in that simplified summary, it is as traditional as horror stories come.

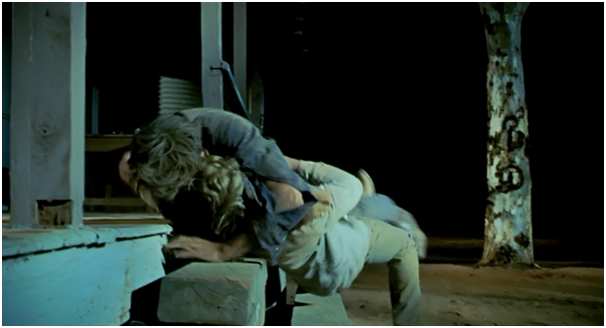

However, the complexity of the relationships between John and the group he finds himself in sets the film apart from the often clichéd horror genre. These relationships are grounded in the concept of mateship, denoting fierce unity and loyalty within a group of (usually) male friends. Their closeness is fierce in every sense. As we see onscreen, these friends proudly drink and joke together, but also insult, fight and kill together. The existence of such a violent friendship seems paradoxical, but the pretence of machismo hides a basic human need; the ‘desire for human contact’ in Kotcheff’s words. [4] As he points out, the fight scene between Dick, Joe and Doc sees them ‘rolling around in the dirt, and they’re all embracing each other – it’s hardly what I would describe as fighting’. [5]

The mateship in the film is all a little strange. The men – particularly those native to the Yabba – are so close and similar, they are almost interchangeable. Yet they fight each other, and in their ferocious unity, outsiders are permanently excluded. They shun the film’s only woman in favour of the physicality of each other, and assert instant superiority over the relatively effeminate John with bone-crushing handshakes. John steps into the Yabba to find that this is simply the accepted order of things. The strange nuances are obvious, but unspoken, and in this way the masculine relationships stand on a foundation of equal parts pride and shame. It is an uncomfortable and pressurised environment for people to live in, so tenuously balancing such extreme qualities. The relationships can only be sustained with an unnatural aid: beer, which is present every step of the way in John’s journey to depravity. By clouding their judgement, it makes their vicious hunting and aggressive misogyny bearable, even forgettable. As John wryly observes, ‘you can burn your house down, murder your wife, rape your child, that’s alright. But… if I don’t have a flaming bloody drink with you, that’s a criminal offence!’. His accomplice perfectly demonstrates the refusal of these people to recognise their faults with the simple retort: ‘you’re mad, you bastard’. Such people are unreachable due both to their diehard loyalty to each other, and their inability to accept outsiders into their tight circles. Threats to their mateship –be they women, animals, even John – must conform, or be excluded.

It is against this backdrop of the destructive consequences of an extreme, masculine, gang-like way of life that the animals of Wake in Fright play their important role. Though John casts himself as an outsider, leaving the men to talk to Janet about his education, his demise has already been foreshadowed. As John drinks before boarding the train to Bundanyabba, the scene is interspersed with shots of caged birds. His wings are clipped – he can’t just leave behind the outback of which he is now a part. Here and there he refuses a beer, but something keeps him coming back to the seedy pleasures he sneers at. Indeed, Rattigan comments that ‘his civilisation, his education, and his middle-class background are defenceless in the face of the very conditions of life in the outback’, and though his downfall has been hinted at, it is made clear that it is John’s inability to find work which leads him to truly surrender to the debauchery of the men he encounters, his despairing push at the door of the Department of Labour leaving a smear of white [6] Without work, John loses the power of class-based condescension, and like the mates he meets, he must settle for baser pleasures. He mentions his girlfriend, Robin, to Janet, who repeats her name before asking if he would take her to England. He answers yes, but she understands the world John has found himself in – a robin cannot fly so far, and John himself is trapped already. Soon enough, their conversation is replaced with sex, whilst the bird imagery in the film is substituted for the constant presence of flies buzzing in and out of shot.

To feel a part of this man’s world, though, is too alluring for John to resist. From within, mateship is desirable, and he strays further from his intellectual nature when deciding to fight a kangaroo one-on-one. The others draw attention to his outsider status, replacing his name with an epithet: ‘you wanna have a go, teacher?’; John takes the bait, replying nonchalantly ‘why not?’. The opportunity to kill, and in the most visceral way possible, absurdly enables John to endear himself to the group. Later he will throw his books away without hesitation, but simultaneously cling to the hope of returning to the city by attempting to hitch a ride with some truckers. Just as he thinks he has secured safe passage to Sydney, a fly flies into his eye – his vision is blinkered, and he seems unable to realise that he cannot be free of the outback. In these two scenes we see the contradictions in the group of mates replicating themselves in John – he too has become a product of mateship in the outback.

From the outback to kangaroos to mateship, which, to return to Rattigan, is ‘probably the single most defining mythic characteristic of Australians’, Wake in Fright has understandably been anchored in Australian culture by many commentators. [7] Its climactic kangaroo slaughter scene was produced by filming licensed hunters in the outback, and it is undoubtedly this level of authenticity achieved by the director which was so upsetting to the Australians who did not recognise what they saw onscreen when the film was released. It permeates the rest of the film, injecting verisimilitude into the barbarism of the people of the outback – the Australian people. But far from losing sight of his own aim of portraying a universal truth that ‘men behave badly sometimes, we’re all capable of it – that’s the whole point’, Kotcheff utilises the remoteness of the Australian outback to show the group at its most unreachable. [8] Their crimes are inexplicable, let alone accountable; an educated teacher and doctor are as cruel as anybody else, and yet they appear to be having nothing but fun. It is the logical, albeit gruesome, limit of mateship according to the film’s study of its disturbing side. Though the film is tied into Australia, it is not shackled by its association with the country. Australia helps the themes of Wake in Fright to achieve their power with the audience, because it is in such settings that vulnerable characters and an aggressive gang mentality can thrive.

Wake in Fright acts as a case study on the destructive effects of an aggressively masculine pack mentality – in short, a sinister mateship – when taken to its logical limits. In its isolation, which allows such behaviour to thrive, the Australian outback is the perfect setting for this horror story. Important though Australia is to the story, the point of the film is not to disgrace its people, rather to show that in these conditions, any human – educated or otherwise – is capable of mindless violence and terror. Kotcheff uses the location to its full potential, as the characters are visibly uncomfortable in the heat, whilst buzzing flies and dusty sets make the outback seem uninhabitable. But it is the vicious kangaroo hunt which shows us the true effects of the men’s actions. They may fight each other, and a gentleman like John may surrender to them, but only when innocent animals are killed for their absurd notion of power and unity do we truly realise what men are capable of. In its unflinching portrayal of the genuine horrors suffered at the hands of ordinary men, Wake in Fright’s power has not diluted in its years away from the spotlight.

Filmography

Kotcheff, Ted, Wake in Fright, written by Evan Jones. [DVD]. (London: Eureka Entertainment Ltd., 2014)

Further Reading

Buckmaster, Luke, Wake in Fright: rewatching classic Australian films, (The Guardian, 2014) https://www.theguardian.com/film/australia-culture-blog/2014/feb/14/wake-in-fright-rewatching-australian-films

Galvin, Peter, ‘Dreaming of the Devil’, Wake in Fright booklet [accompaniment to Eureka Entertainment Ltd.2014 edition DVD], ed. by Craig Keller & Kevin Lambert, (London: Eureka Entertainment, 2014), 15-27

Jennings, Kate, ‘Home Truths: Revisiting Wake in Fright’ in The Best Australian Essays 2009, ed. by Robyn Davidson, (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2009), 51-71

Kotcheff, Ted, ‘Ted Kotcheff Interview’ from Wake in Fright, dir. Ted Kotcheff, written by Evan Jones. [DVD]. (London: Eureka Entertainment Ltd., 2014)

Langford, Barry, Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005)

Martin, Adrian, ‘Breaking Badland’, Wake in Fright booklet [accompaniment to Eureka Entertainment Ltd. 2014 edition DVD], ed. by Craig Keller & Kevin Lambert, (Eureka Entertainment, 2014), 5-13

O‘Loughlin, Toni, Oz wises up to its horror heritage, (The Guardian, 2009) https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jun/19/wake-in-fright-horror-film

Rattigan, Neil, Images of Australia: 100 Films of the New Australian Cinema, (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1991)

[1] Neil Rattigan, Images of Australia: 100 Films of the New Australian Cinema, (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1991), p. 306.

[2] Ted Kotcheff, ‘Ted Kotcheff Interview’ from Wake in Fright, dir. Ted Kotcheff, written by Evan Jones. [DVD]. (Eureka Entertainment Ltd., 2014).

[3] Toni O‘Loughlin, Oz wises up to its horror heritage, (The Guardian, 2014) https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jun/19/wake-in-fright-horror-film [last accessed 7th January 2015].

[4] Ted Kotcheff, ‘Ted Kotcheff Interview’ from Wake in Fright, dir. Ted Kotcheff, written by Evan Jones. [DVD]. (Eureka Entertainment Ltd., 2014).

[5] Ted Kotcheff, ‘Ted Kotcheff Interview’ from Wake in Fright, dir. Ted Kotcheff, written by Evan Jones. [DVD]. (Eureka Entertainment Ltd., 2014).

[6] Neil Rattigan, Images of Australia: 100 Films of the New Australian Cinema, (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1991), p. 307.

[7] Neil Rattigan, Images of Australia: 100 Films of the New Australian Cinema, (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1991), p. 306.

[8] Ted Kotcheff, ‘Ted Kotcheff Interview’ from Wake in Fright, dir. Ted Kotcheff, written by Evan Jones. [DVD]. (Eureka Entertainment Ltd., 2014).