Hapless Wallace and his faithful dog Gromit appear again on screen for a dramatic adventure in The Wrong Trousers (1993). The inventors’ worldsget thrown upside down by Gromit’s birthday present: a pair of mechanical trousers. These were intended to self-walk Gromit, but when Wallace’s debts lead him to letting out a room to a penguin, the trousers are put to dangerous misuse. When Wallace suddenly becomes stuck in the Techno-Trousers and the controls have disappeared, it is Gromit to the rescue. Stealing the trousers for his own devious purposes, Feathers McGraw is revealed to be a wanted criminal. The climax sees a high-speed toy train chase through the house, as the duo capture Feathers once and for all.

Nick Park has been part of the creation of many well-recognised stop motion productions that feature animals. These include Creature Comforts (2003), Shaun The Sheep (2007), Chicken Run (2000) and the Wallace and Gromit films. These productions sit firmly in the family film genre as the animals make for childish stories but also allow for a more adult humour. Park creates animal characters that delight audiences because each anthropomorphised figure is very unique, having its own witticisms that make it funny.

| Creature Comforts (2004) |

This film exhibits brilliant characteristic style produced by the stop motion film technique. Claymation is a method of animation involving ‘deformable’ plasticine models that have to be moved for every frame.[i] Known as Aardman Animations ‘speciality’, claymation is how the Wallace and Gromit are created.[ii] This form has a significant role in representing animals on screen. Park stated that claymation has a ‘magical effect’ and that animals coming to life are‘suddenly gaining a character’.[iii] Therefore, the textures produced allow for a manipulation and certain playfulness with animals’ shapes. For instance, when Feathers is captured inside a glass bottle, the director is clearly drawing attention to his comical shape because a real penguin could not do that. This style therefore allows for a extensive manipulation of an animals’ character that you could not do in real life.

Examining Gromit as a complicated blend of human and animal is highly interesting. He is anthropomorphised from the very beginning of the film: he makes Wallace’s breakfast, carries in the post, and settles down reading a newspaper. Gromit’s actions mirror the loyal qualities of a dog however, he does them as a human would. He has humanistic traits, such as standing on two legs and sitting at the table. But the most distinctive human characteristic, speech, is omitted from him. The animators have instead focused purely on his expressions and mannerisms to create a human/animal hybrid. A distinctive feature of Gromit is his unibrow, which displays all of his emotions in the tiniest movements. Nick Park expressed in an interview how Gromit was initially ‘going to have a mouth and do a lot of growling, but I soon saw how hard that was, so I started tweaking his eyebrows instead – and that did everything’.[iv] Therefore, this film’s format enablesanimals to havea ‘magical’ coming to life that is absent in the real world.

Gromit is additionally show to have a higher intelligence than his human owner, highlighting that animals have a useful place in the home. The animators play with this through instances of Gromit’s reading. We see inside a paper the title, ‘Dog reads paper’. In his kennel we see three books, ‘STICKS’, ‘POODLES’ and ‘SHEEP II’. Feathers pick out ‘Electronics For Dogs’ from Gromit’s bookshelf. A newspaper, is entitled the ‘Daily Beagle’. All these texts within the film give the film a high level of self-consciousness. Gromit is after all a dog, and he is reading the dog versions of books and newspapers. This suggests that there are other intelligent dogs in this world. There is semiotic weight behind these book titles, as Gromit seems to only read books that would be interesting to dogs. Additionally, Gromit appears intelligent due to the animation form, as it would be near impossible to train a real dog to read.

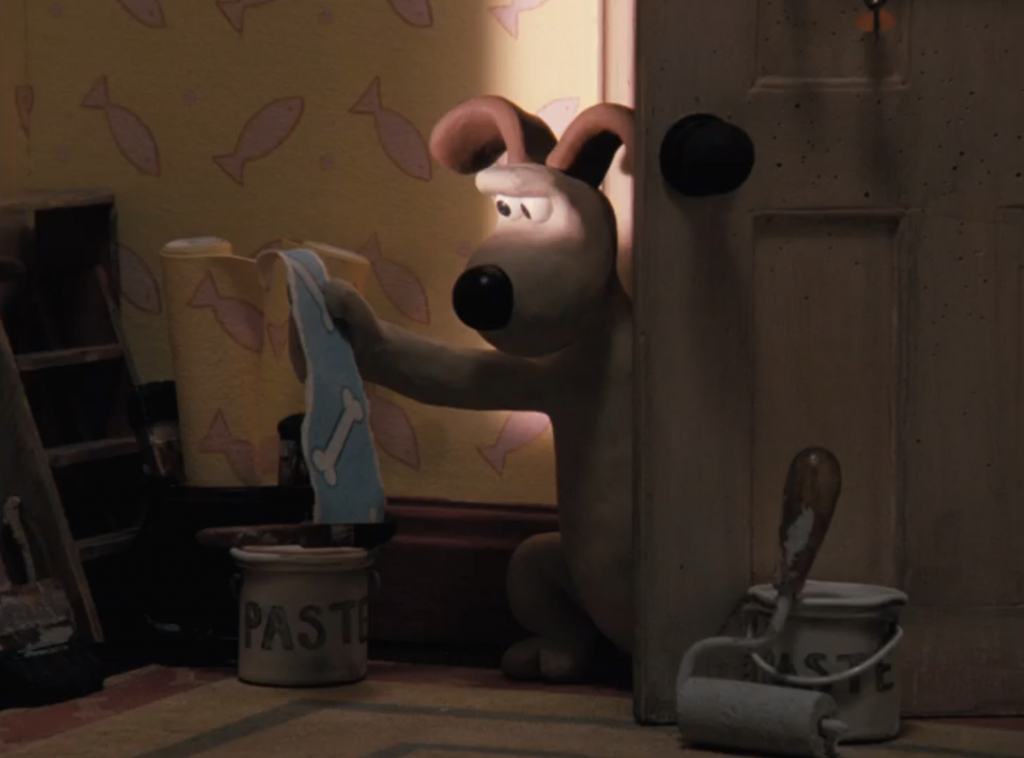

Sympathies align with Gromit when Feathers moves into the home. The penguin is invading Gromit’s space, creating a tension between dog and bird. They are fighting for Wallace’s attention: Gromit as his pet, as dogs typically require human approval, but for Feathers it is an exploitation of the human to enable his crime. Even though Feathers is an infuriating lodger for Gromit, as an audience we find his acts of annoyance humorous, such as the late night music and painting over Gromit’s bone wallpaper to fish (Fig. 1). This is because they are satirising the acts of a human that we can relate to and therefore find amusing.

Fig. 1. Gromit disproving at the new wallpaper in his room

A captivating scene that shows the two animals interacting from a distance is when Gromit follows Feathers, spying on his activities. There are a multiple close-up shots of the two characters, and the cutting back and forth establishes the characters as oppositional forces. In order to hide, Gromit puts a box over himself and cuts out the shape of his eyes. Park creates a genius point-of-view shot through the holes of the box (Fig. 2). The box resembles binoculars, zooming in on Feathers’ movements, which is a fun play on the shot, because a box could not really do this. To see the penguin ‘floating like a milk bottle’ rather than waddling is sinister, and combined with a sudden robotic head turn toward Gromit (and therefore us) is unexpected.[v] Park persistently utilises thefeatures of a spy movie by using asetting that is reminiscent of a spyingscene: a dark alleyway with tall shadows produced by the penguin and surrounding objects. This is a parody of a secret agent film, because even though tense non-diegetic music is playing underneath, the use of animals downplays the seriousness of the situation. The revealing of Gromit hiding in a dog-food box (Fig. 3) provides a comic release of tension.

| Fig. 2. Point-of-view shot, showing Feathers McGraw | Fig. 3. Dog-food box is comical |

It is impossible to ignore the finale of the train chase in The Wrong Trousers, as it is a highly stylised, incredible bit of animation.Gromit’s fast-paced track laying is an incredible feat (Fig. 4). The scene has a Western style, containing traits such as cloud wallpaper, Western “chase” music and having a pistol as Feathers’ weapon. This is highly comical because it is impossible to have this happen in a living room. Here, the animals are cast opposite each other as good vs. evil. A fight between a dog and a penguin should predictable, but here Feathers has the upper hand with the gun. There is an element of danger as Gromit is shot at, yet the audience is safe in the knowledge that Gromit will win. Here, Gromit is the hero, not Wallace. The dog has fallen into the archetypal role of a pet dog displaying heroism.

| Fig. 4. Train chase with Gromit and Feathers |

Audiences tend to find animated animals humorous when they are doing something out of the norm. It is the unexpected that is comical. This is true of The Wrong Trousers as the penguin is not a typical villain. As a penguin, Feathers would be affiliatedas being a ‘cute’ figure.[vi] Feathers is very purposely subverted with this. By having a surprising villain, the film ‘suddenly became a Hitchcock thriller, with a bit of “Put a rubber glove on your head and you’re a chicken” humour, too’.[vii] Feathers’ disguise is interesting, as a household glove depicts domestic life, which Feathers clearly is not a part of. Feathers is not a threatening figure, and it is extremely comical that a false chicken commits crimes and the human police are after him. This film demonstrates how any animal can be a villain, but only in the domain of comedy.

The inherent goodness of Gromit as man’s best friend is prominent throughout the Wallace and Gromit series. Their relationship is heartwarming to witness, as they clearly care for one another, andyet it is also complicated. Wallace often says, “Good dog” and therefore establishes himself as Gromit’s owner. Gromit does have agency, and has his own mind, shown by his reading and expressions. He is not just a loyal pet, he is crafted to be a hero, a companion and an intelligent assistant. However, all these things are intrinsically linked back to Wallace. Wallace did not show the same loyalty to Gromit by allowing Feathers to invade his space. Yet Gromit still comes back to help him. To forgive Wallace marks a compassionate side of an animal, which is mirrored in the forgiving nature of the plasticine. We associate plasticine with our childhoods, a substance commonly played with in our youths. To create a villainous character out of a child-friendly material is difficult. Park had to rely on the movement and dominating black body of the penguin to connote an evil figure.

The Wrong Trousers is comparable to Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr Fox (2009). While they both contain self-awareness of form, using stop motion to create a lighthearted humour, it is clear that Anderson’s film is highly stylised in terms of symmetry and jerky movements in the characters. The Wrong Trousers however,contains much smoother transitions, every alteration is carefully manipulated to ensure perfect movement of both humans and animals. The form is essential in communicating animals to us in a different way to real-life action films. Animation allows for depth and breadth to the anthropomorphism, creating comical and original characters in Gromit and Feathers.

Bibliography

Aardman Animations, ‘20 Questions with Nick Park’, YouTube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jwp-0oEoJM> [accessed 20 December 2015]

Abbot, Kate, ‘How we made Wallace and Gromit’, The Guardian (2014) <http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2014/mar/03/how-we-made-wallace-and-gromit> [accessed 20 December 2015]

Gibson, Owen, ‘A one-off quirky thing’, The Guardian (2008) <http://www.theguardian.com/media/2008/jul/21/television> [accessed 18 January 2016]

TV Tropes, ‘Everything’s Better with Penguins’, TV Tropes (2016) <http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/EverythingsBetterWithPenguins> [accessed 17 January 2016]

TV Tropes, ‘Stop Motion’, TV Tropes (2016)<http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/StopMotion> [accessed 2 January 2016]

Further Reading

On Claymation as a film technique: http://www.claynation.co.uk

Exploring how Wallace and Gromit was made inPeter Lord and Brian Sibley’s book,Creating 3-D Animation (New York: H. N. Abrams, 2004)

Aardman Animations website, showing all their products: http://www.aardman.com

Interesting tropes in The Wrong Trousers: http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/WesternAnimation/TheWrongTrousers

[i] Creative Animation World 3, ‘Cut Out Animation & Clay Animation’, Creative Animation World 3 (2013) <https://caworld3.wordpress.com/tag/clay-melting/> [accessed 18 January 2016]

[ii] TV Tropes, ‘Stop Motion’, TV Tropes (2016)<http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/StopMotion> [accessed 2 January 2016]

[iii] Owen Gibson, ‘A one-off quirky thing’, The Guardian (2008) <http://www.theguardian.com/media/2008/jul/21/television> [accessed 18 January 2016]

[iv] Kate Abbot, ‘How we made Wallace and Gromit’, The Guardian (2014) <http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2014/mar/03/how-we-made-wallace-and-gromit> [accessed 20 December 2015]

[v] Aardman Animations, ‘20 Questions with Nick Park’, YouTube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6jwp-0oEoJM> [accessed 20 December 2015]

[vi] TV Tropes, ‘Everything’s Better with Penguins’, TV Tropes (2016) <http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/EverythingsBetterWithPenguins> [accessed 17 January 2016]

[vii] Kate Abbot, ‘How we made Wallace and Gromit’, The Guardian (2014) <http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2014/mar/03/how-we-made-wallace-and-gromit> [accessed 20 December 2015]