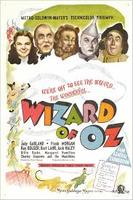

The Wizard of Oz is about a small-town girl in the big city–the Emerald City. Dorothy lives on a farm in Kansas with her dog Toto. When she is knocked unconscious during a hurricane, she wakes up to find herself in the magical world of Oz, filled with a myriad of unusual creatures. She must travel the yellow brick road to the Emerald city in the hopes that the wizard can return her home. Luckily, help arrives in the form of the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion who join her on her journey hoping to ask the Wizard for a brain, a heart and courage. Before they reach their destination, the group must avoid falling into the clutches of the evil Wicked Witch of the West and her flying monkeys. Upon reaching the dazzling Emerald City, Dorothy discovers the Wizard to be a fraud who possesses no real magic. It is up to her alone to get herself home by tapping the heels of her ruby slippers and believing that there really is ‘no place like home’. Dorothy awakens in Kansas surrounded by her family, though she is not convinced that the land of Oz and all its curious creatures were simply a dream…

As a fantasy, logic and realism are not priorities in The Wizard of Oz; it stands to reason therefore that the representation of animals in this film does not always make complete sense. In the ‘real’ sepia-toned world of Dorothy’s aunt and uncle’s farm in Kansas, the animals are simply animals. They can’t talk and (apart from Toto) they have little relevance to the story at all. In Oz all rules about animal representation go out of the window, with the realism of the animals portrayed becoming vastly varied. Toto, as a reminder of Dorothy’s home, is played by a real dog called Terry, whilst most of the animals of Oz are either played by humans or are props. The cowardly lion essentially has all the qualities of a human, he speaks, he stands on two legs, he shows emotion, only the costuming and brief animalistic mannerisms remind us of his species. At the other end of the spectrum, the owl and vulture that appear in one scene are props, probably made like puppets, with light up, bright red eyes that show no life-like characteristics at all. Yet what they have in common is the lack of even an attempt to create any sense of realism. When creating the land of Oz which revels in the notion of things not being as they seem, the filmmakers are constantly playing with the concept of what it means to be ‘animal’.

The animals on the farm in Dorothy’s home in Kansas are definitively and intentionally realistic, largely used to simply add life to a set. When the film opens, Dorothy runs through the farm to tell her aunt and uncle about Mrs. Gulch’s cruelty to Toto, the cow and chickens that appear on screen are part of the background, ignored by Dorothy as she scatters the chickens out of the way. When she reaches her aunt and uncle, they are removing chicks from the incubator which has ‘gone bad’ meaning they’re ‘likely to use a lot of [their] chicks’. Real chicks are used here, but they again serve as simply a device to show Aunty Em and Uncle Henry’s pragmatism compared to Dorothy’s compassion. Her aunt and uncle are counting the chicks for business purposes whilst Dorothy laments, ‘oh, oh the poor little things’, pressing one to her cheek. Furthermore, Dorothy’s sympathy towards the chicks could be seen as evidence of her ‘symbolic association with the farm’s doomed, flightless birds’ which is an essential part of her character who longs to fly away ‘somewhere over the rainbow’.[1] In fact, all the interactions between the humans and the animals in Kansas are to serve a purpose such as to characterise the humans or set. Interestingly, this mirrors the use of these animals within the world of the film, as farming uses animals solely for human gain in the creation of produce. However, the filmmakers are not solely trying to emphasise realism in these scenes, but the lack of magic. This is made clear by the sepia colouring of these scenes which shows the filmmaker’s intention convey the dullness, yet also the warmth of Dorothy’s home. By making the animals so insignificant that they merely serve a purpose for the humans and are deprived of all personality, they contribute to this non-magical, mundane reality.

The only animal in Kansas that retains what we might call a ‘personality’ is Toto, who is also the only animal to transcend the barrier between Kansas and Oz. This places him in the middle of the spectrum of animal characters in the film. He is played by real dog like the other animals in Kansas, yet unlike these animals he is given characterisation and importantly an ability to communicate with the human characters. For example, in the scene in which Mrs. Gulch takes Toto away, he escapes returning to Dorothy and barking beneath her window. This scene shows that Toto has thoughts and an emotional connection to his owner- he looks around before he escapes the basket as if wondering where he is, and he knows which window is Dorothy’s. When in Oz however, we are constantly reminded of his normality and his symbolic connection to Dorothy’s home when he is contrasted with the other animals. In the scene in which Toto and the gang rescue Dorothy from the castle of the Wicked Witch of the West, it is Toto that leads them to the door, harking back to the earlier scene when he returns to her window. Furthermore, when placed into direct contrast with the cowardly lion whose animalistic features are extremely played down, Toto’s become even more obvious. When the cowardly lion is disguised as a guard wearing human clothes, the vast size difference only adds to the clear visual symbol that separates these animals as being from two very different worlds.

When we consider the animals of Oz, the spectrum of ‘animalism’ is opened up and two particular animals flip the use of animals in Kansas on its head. Instead of real-life animals serving as props, the vultures and owls that appear in the haunted forest are actually props used in replacement of real animals. The birds are puppets with menacing glowing red lights used for their eyes. Similarly to the animals in Kansas, these birds characterise the set, adding to the creepy atmosphere of the forest. Yet the obvious reversal of the realism in Kansas emphasises that Oz is a world where everything is turned on its head. Furthermore, the hybridity of these object-animals creates a sense of the ‘uncanny’ as they are almost but not quite real. These creatures are almost entirely non- animal, showing the filmmakers’ distinct intention to not create a sense of realism in the world of Oz and to emphasise the fantasy elements. This is especially noticeable when we consider that many other real-life birds appear in Oz such as the flamingos in the Emerald City, there is clearly no desire to create a sense of continuity in the animals in Oz.

On the other end of this spectrum, the Cowardly Lion is the least ‘animal’ of all the non-human creatures in Oz, so much so that it is easy to forget he even is an animal. Before the days of special effects that allowed animals to talk on screen, the filmmakers had to make a choice between presenting the Cowardly Lion as a real animal or giving him his all-important oxymoronic characterisation- they clearly chose the latter. The prioritisation of his ‘cowardly’ characteristics over his ‘lion’ characteristics is clear from his introductory scene. He bursts into the scene with a loud off-screen roar accompanied by a crescendo in the frenetic score. We first see him raised on a tree trunk, on all fours, still growling. This importantly ensures the audience’s first impression of the Cowardly Lion is that he is, well, distinctly lion-like and rather intimidating. However, seconds later he bounds down from the tree trunk on two legs and a close-up of his face shows us that he is played by a human. Yet the characters remain afraid with individual close ups showing the fear on their faces. The key moment that switches the Cowardly Lion from a frightening beast to a comical character also serves as the moment it becomes clear he is perhaps more human than lion. This occurs when he stands up on two legs puts his fists up and says ‘Put ‘em up, put ‘em up’. These actions are distinctively human, with the accent reminiscent of a New York gangster as the filmmakers play with the idea of what human characteristics animals would have. This is an important set up of his key characteristic, his cowardliness and it provides a comical contrast for the audience. The first impression of the Cowardly Lion serves both to set up the comedy that comes with the oxymoron of a ‘cowardly lion’, whilst simultaneously signposting to the audience that this incredibly human character really is a lion, since this will be easy to forget later on. As soon as his cowardliness is revealed when Dorothy bats him on the nose, the prioritisation of this characterisation over his animal qualities occurs. All his actions become human-like and he is shot in the same way as the other characters. As he cries to Dorothy, performing a typically human emotional reaction, an over the shoulder conversational shot is used which puts the two characters on the same level, emphasising their similarity rather than their difference.

To sum up the incredibly varied representation of animals in the film, we can see that the choices made in presenting these animals very much depended on what the filmmakers wanted to convey firstly about the worlds they exist in, and secondly the characters purpose in the story. In Kansas animal representation is focused on conveying realism, yet almost a sterile realism that creates world which is duller than reality. By making the animals into nothing more than live props which only serve the humans in various ways, all the ‘magic’ that can come from a human- animal connection is taken away. In Oz on the other hand, the fantasy is over- emphasised through the nonsensical aspects of this world. The animals are a very important aspect of conveying this fantasy as they show anything is possible in Oz, including an anthropomorphised lion who’s cowardly nature overrides all of his animalistic qualities, and puppet-like birds with light up eyes. Toto the dog exists somewhere in between these polar opposite forms of animal representation as he has a personality and a purpose, yet he remains to all intents and purposes an ordinary dog. His ability to move between Kansas and Oz serves to simultaneously remind the audience of the differences between the two worlds, but also to show that they are closely intertwined.

The decisions made in the presentation of the animals in The Wizard of Oz were not made in an attempt to convey realism, in fact the filmmakers appear to have been trying to convey the exact opposite. By making the animals in Oz various forms of hybrid, human-animal hybrids, object-animal hybrids, the filmmakers add whimsy and distinguish them from the simple and real farm animals at Dorothy’s home in Kansas. This has been a technique that has continued into many modern fantasy films, even with the advent of CGI, as films must still find ways to distinguish their animal protagonists from those that serve a lesser purpose in the film. In the Chronicles of Narnia films for example, human-animal hybrids such as centaurs and fawns are distinguished from animals that serve less important purposes, such as the horses ridden by the soldiers. The added element of whimsy and mystery created by the variety of animal representation is an essential ingredient in the creation of the magical world of Oz.

[1] Bird-Watching in Dorothy Gale’s Oz, By TOM BLUNT, January 15, 2013

Bibliography:

Tom Blunt, ‘Bird-Watching in Dorothy Gale’s Oz’, Signature, 15 January 2013, https://www.signature-reads.com/2013/01/bird-watching-in-dorothy-gales-oz/ [accessed 8 January 2019]

Aljean Harmetz, The Making of The Wizard of Oz, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013)

Horatia Harrod, ‘Stormier Than Kansas: How The Wizard of Oz was Made’, The Telegraph, 25 December 2015, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/film/the-wizard-of-oz/making-of-facts-trivia/ [accessed 7 January 2019]

Alexander Sergeant, ‘Scrutinising the Rainbow: Fantastic Space in The Wizard of Oz (1939)’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 2 (2011), 1-15

Further Reading:

Alexander Doty, ‘“My beautiful Wickedness” The Wizard of Oz as Lesbian Fantasy’, in Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, ed. by Henry Jenkins III, Tara McPherson & Jane Shattuc (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2002), 138-162

Aljean Harmetz, The Making of The Wizard of Oz, (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013)

Alexander Sergeant, ‘Scrutinising the Rainbow: Fantastic Space in The Wizard of Oz (1939)’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 2 (2011), 1-15