Following the life of Moses, The Prince of Egypt tells an adaption of the story of the Book of Exodus. In the opening scene of this animated musical, the audience are introduced to Ancient Egyptian culture as a significant importance is placed on their religion through the enormous statues of their gods. These gods, specifically the sun god Ra, are portrayed as half human-half animal and therefore demonstrate a hierarchy in which a hybrid human-animal being is more powerful than the slaves who have built the statue, and the Egyptians who rule the empire. With this form being applied to gods, it begs the question why animal attributes are desired so highly within Ancient Egypt and why, through these attributes, the being is worthy of worship. Within the scene and musical number ‘Deliver Us’, this human-animal hierarchy is emphasized not only by the significant size of these statues but also the animality of the slaves.

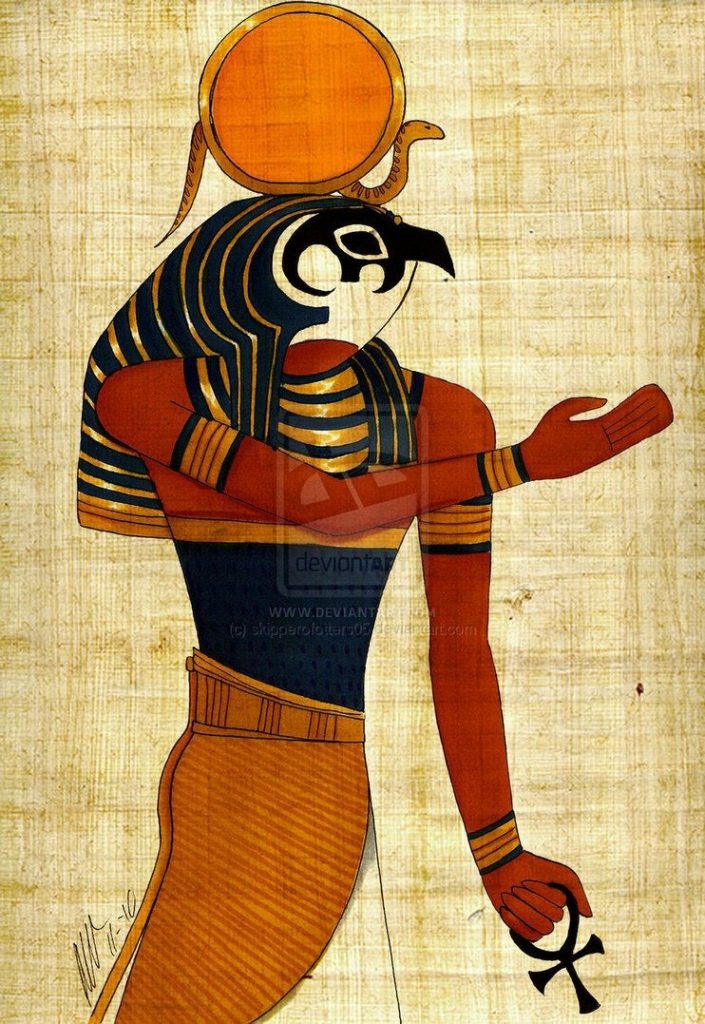

In the background of a wide angle shot, [Fig. 2], there is an evident human-animal power hierarchy as the statue of the sun god Ra (a half human-half heron god) is being built, and the Hebrew slaves are seen working tirelessly. Ra’s importance, heightened by his position in the center of the screen, allows the audience to associate him with power as he is also the ‘center’ of the Egyptian empire, and therefore extremely important to their culture. As this shot introduces the statue of Ra, a human-animal relation is evident through the portrayal of the slaves. An emphasis is placed on the Hebrew slaves, within the outer edges of the shot, as they are shown in minimal clothing and carrying bags of sand bigger than their weight can lift. As they struggle, this shot depicts the slaves as animalistic as they are forced to work similarly to working donkeys in poorer countries [Fig. 3]. Animals are seen as inferior to humans due to a lack of understanding between the two, and this is therefore applied to slaves as well, and they are treat as unintelligent. Consequently, slavery has long been related to animality as both demonstrate significant exploitation by humans. It is interesting, but not surprising, that slaves have been portrayed this way, as a result of a continuous history of slavery in which they are depicted like animals because they are treat like them. And so, within this film, the Hebrew slaves are diminished and animalised to both show their poor living conditions but also to contrast more greatly the power of the animal gods.

As the statue is stood upright, a shadow casts over the Hebrew slaves and illustrates the power dynamic between them and the animal god. In this scene, a close up shot of the slaves shows the evident fear in their faces as they are towered over by the statue [Fig. 4]. Each worker, if analysed closely, show a different reaction to the God, for example fright, anger or shock – all of which are negative. In [Fig. 4] it is clearly evident of the massification of the slaves, much like a cattle, in which the Egyptians can easily manipulate and control. In this case, the Egyptians use violence and death to control the slaves in a similar way that is used with animals in training them. They are, similarly to slaughterhouse animals, forced out of fear into submission. As the Hebrews cower in minimal clothing, they are diminished. Much like a child in minimal clothes, they slaves are seen as unintelligent beings capable of being easily manipulated. Just like the slaves must do as they are told, so too does the working animal. When depicting these slaves as animals it is important to understand that in this exemplary representation they are misunderstood and are made this way both for the audience to understand the harsh treatment of them but also to depict how the Egyptians see them – as animals they can control. There is also use of camera and character positioning [Fig. 4] to show the superiority of the statue as a high angle shot looks down on the slaves, representing their inferiority. This shot represents the animality of the slaves by depicting them how humans would look at animals. To illustrate, as a human would look down on a pig or dog (an animal easily used to evoke human authority), this shot represents a specific authority looking down on them, as the majority of them are on both their hands and knees.

The Egyptian god Ra was ‘represented as a heron’.[1] Arguably, the representation of this god is a static one – a statue. This is interesting as it in no way provides confirmation that this being is real, and therefore suggests a lack of truth in Egyptian religion, and the lack of realism in animals being represented as gods. However, although the statue of Ra is not necessarily a character, his power throughout this scene is evident and his presence is undeniable within Ancient Egyptian culture.

The quasi-animal forms of the Egyptian gods allow the audience to understand more about the human-animal relations in ancient Egypt and how specific animal attributes, such as flight, were admired and therefore gods were worshipped. Animals were worshipped through their ‘attractive qualities that the ancient Egyptians perhaps admired and wanted to emulate, for example; strength; the ability to ward off predators; protective nature; nurturing characteristics and connections to rebirth’.[2] Through such powerful characteristics, Egyptians associated animals as gods because they were able to do things they could not, and therefore held more power in their everyday lives. Watterson discusses the reason Egyptian gods are seen as animals is so, unlike other religions, they can see their gods around them and in everyday life. She states ‘The Egyptians could daily watch the sweep of a falcon across the sky, whereas the number of people who have beheld the Angel Gabriel is not large!’[3] This furthers my argument and demonstrates the Egyptians could be surrounded by the animals they deemed gods but were also able to witness their ‘supernatural’ abilities in person. Furthermore, through combining attributes that humans are not capable of, such as flight, with something like bipedalism and intellect to show authority, their gods are much more powerful. Egyptian gods were seen as great, powerful beings as they were combined of both human and animal attributes and given the best characteristics of each. To illustrate, the half human-half bird portrayal of Ra shows he is a god with both the power of flight and strength from an animal but also the compassion and understanding of a human. Further, this creates a physically powerful god but also a connectable one. If humans could fly, or animals could speak the same as humans, we would question one more superior than the other whereas here is a being combined of the two. The Egyptians therefore created a hybrid being combined of all the best characteristics of multiple species. The Prince of Egypt, through its focus on the power Egyptian animal-human gods held in their religion, illustrates the power animals held, and arguably still do, within a culture obsessed with otherworldly features.

The story told in The Prince of Egypt, – a story which has been told and retold many times – is ‘made more dramatic, more shocking, more exciting in order to be seen as a better fit for the silver screen’.[4] Not much is confidently known about Egyptian religion and the culture portrayed in this film, as we only have minimal knowledge of how they lived through artifacts and archaeology finds. As this is a family animation film, it would be incredibly difficult to portray a realistic representation of Ancient Egypt, due to the excruciating living conditions of the slaves and the brutality of the Pharaoh, and so an exact representation would be both impossible (as no one alive has witnessed in person the culture) and unpopular. However, the desire and worship of human-animal gods is an accurate representation and shows the importance of religion in Ancient Egyptian culture.

Arguably, then, are animals portrayed as the most powerful creature’s in Ancient Egypt as they are worshipped in everyday life and viewed as Gods? Are animals more powerful than humans? Arguably, yes, Ancient Egyptian culture did believe animals to be more powerful and, in desiring their superior characteristics, deemed them spirits and gods of the natural world. The Prince of Egypt therefore evokes the idea that attributes such as strength and flight within animals are desired by demonstrating a higher power, through these said attributes, over the slaves but also the rest of Egypt as it is them who are worshipped, not the Pharaoh and his subjects. Consequently, The Prince of Egypt shows a hierarchy in which animals are more powerful – are Gods, and presents the audience with a portrayal that the combination of the two – both human and animal – presents an omnipotent being suitable of worship.

Footnotes

[1] Caroline Seawright, ‘Egypt: Animals and the Gods of Ancient Egypt’, Tour Egypt, 2011, <Egypt: Animals and the Gods of Ancient Egypt (touregypt.net)>, [accessed 16 January 2021]

[2] n/a, ‘ANIMAL: Sacred animals of ancient Egypt’, Reading Museum, 2020, < ANIMAL: Sacred animals of ancient Egypt | Reading Museum>, [accessed 16 January 2021].

[3] Barbara Watterson, ‘Gods of Ancient Egypt’, (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2003), < Gods of Ancient Egypt – Barbara Watterson – Google Books> [accessed 16 January 2021]

[4] Stephanie Hertzenberg, ‘7 Facts About Moses Movies Always Get Wrong’, Beliefnet, n/a, < 7 Facts About Moses Movies Always Get Wrong – Beliefnet>, [accessed 16 January 2021].

Bibliography

n/a, The Making of The Prince of Egypt, online video recording, YouTube, 25 June 2013, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B_aWmJJZj6Q&feature=emb_logo> [17 November 2020].

n/a, ‘ANIMAL: Sacred animals of ancient Egypt’, Reading Museum, 2020, < ANIMAL: Sacred animals of ancient Egypt | Reading Museum>, [accessed 16 January 2021].

Hertzenberg, Stephanie, ‘7 Facts About Moses Movies Always Get Wrong’, Beliefnet, n/a, < 7 Facts About Moses Movies Always Get Wrong – Beliefnet>, [accessed 16 January 2021].

Seawright, Caroline, ‘Egypt: Animals and the Gods of Ancient Egypt’, Tour Egypt, 2011, <Egypt: Animals and the Gods of Ancient Egypt (touregypt.net)>, [accessed 16 January 2021]

Watterson, Barbara, ‘Gods of Ancient Egypt’, (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2003), < Gods of Ancient Egypt – Barbara Watterson – Google Books> [accessed 16 January 2021]