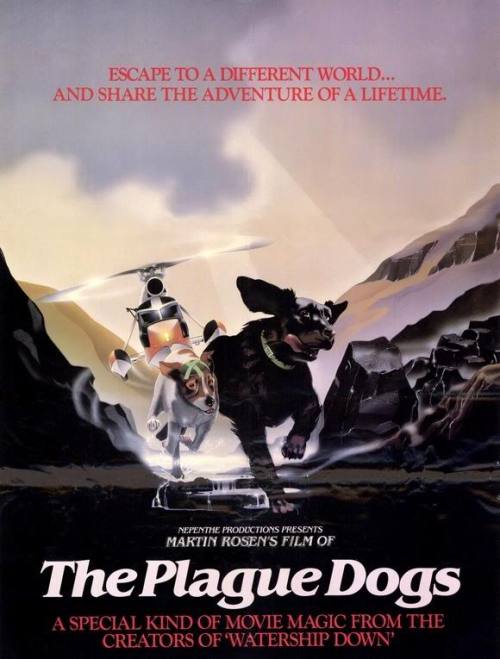

Based on Richard Adams’ 1977 novel of the same name, The Plague Dogs[1] follows the story of Rowf and Snitter, who escape from an animal research centre after Rowf’s cage is left unlocked, finding themselves in the heart of the Peak District. The dogs hope to find a master, but every human encounter is hostile. Running out of options, they see their only hope of surviving is to live like wild animals, and so they begin to kill and eat sheep.The dogs cause much disruption for humans, as word gets out that the testing centre is working with the Bubonic plague, and panic spreads with the news that it’s possible Rowf and Snitter are carrying the disease.The authorities set out to hunt down and shoot the dogs, as they flee towards the sea, and the film ends with the dogs swimming in the ocean, leaving it ambiguous as to whether they survive.

The Plague Dogs is a feature length animated adventure. Usually, both animation and adventure point in the direction of the family film, yet The Plague Dogs is not suited to younger audiences due to violent and upsetting scenes. The animation enables some animals in the film to be anthropomorphised by giving them voices in various regional accents. Aside from these voices, the animals are portrayed very accurately, capturing realistic movements and actions. Animators are often encouraged to study anatomy, by bringing live animals into the studio, and when viewing The Plague Dogs it is clear each animal was studied closely, as the films provides visual details into the animal representation[2].In one scene Rowf urinates, followed by Snitter urinating in the same spot after sniffing it, in order to mark his territory, just as a real dog would.It is these small details that create an authentic animal portrayal; it is easy to forget that the animals on screen were constructed by humans. The film covers real world concerns such as vivisection, and so the realistic portrayal of animals increases the verisimilitude of the world captured in the film.

Throughout the film, the spectator empathises with the dogs and not the humans. The film’s initial shot takes place under water as Rowf undergoes an endurance test, in which he must swim for as long as possible until he begins to drown and is fished back out. As Rowf sinks to the bottom of the tank, the shot is taken from his perspective, and the faces of the researchers loom over the tank. The low angle beneath the water’s surface emphasises the superiority the humans have over Rowf as he helplessly sinks. When Rowf is placed onto the examination table, the men in lab coats look down upon him, and a worm’s eye view places the spectator in Rowf’s position.One of the scientist’s hands holds Rowf down whilst the other places a tube down his throat. The hand and tube appear colossal as they come down upon Rowf at this angle, just as they might to a dog. Whilst dogs are nearly always physically lower than humans, these kinds of shots are seen throughout, and the extremity of the worm’s eye angle emphasises the power humans assert over animals.

Rowf struggling in the endurance test

The film involves little human interaction, enabling the viewer to easily empathise with the dogs. In one of the first human encounters, the frame is entirely black, and it is only when a match is lit that a face is revealed. Due to the low-lighting from the match under his chin, the human is presented as threatening from the very beginning.

Rarely are the faces of the humans shown, often only showing the lower bodies from the level of a dog. In the rare moment that a human’s head is captured, the faces are always obstructed. For instance, when the animal researcher is shown injecting rats, they wear a protective mask that covers the head area entirely, whilst other times faces are shrouded in shadow. The only time a human’s perspective is shown, it is filtered through binoculars, so that audiences never come directly into contact with the human gaze. This same human displays the only friendly human-animal encounter in the film, but is killed when Snitter accidentally steps upon the trigger of the man’s gun. When the man’s face is shown it is covered with his hands and also blood. The face harbours human emotion, and the fact that it is rarely shown does not allow the audience to make any connection with humans in the film. Significantly, the one friendly interaction between human and animal results in death, and so the one hope for Rowf and Snitter is destroyed. Rosen uses open-form narrative, in which human voice-overs discussing the escaped dogs are heard, yet they are not visibly present within the frame; again, we cannot put a face to the human.

When Snitter accidentally shoots the man

Rosen encourages audiences to empathise with the dogs in order to voice wider concerns about vivisection. Anti-vivisection advertisements often used dogs as the central image, lying helplessly on the ‘torture trough’ as the corrupt vivisector looks sadistically on, much like the initial scene with Rowf[3]. Using dogs as the protagonists certainly pulls on heart strings, as no one likes to imagine such cruelty inflicted upon man’s best friend.

Rowf being tested on

Despite the dog’s escape, the narrative recurrently returns to the testing centre. As one shot zooms out revealing the centre, a sign stating: ‘No authorised persons allowed beyond this point’ is exposed, and on the floor is the word ‘STOP’. Rosen allows us into this forbidden space, placing the spectators in a privileged position and inviting them into the unauthorised territory. Inside, a monkey is shown inside a small steel container, with barely enough room. Despite this crammed space, Rosen allows the spectator into this container, so that it is only them and the monkey that occupy the space. Monkeys are genetically similar to humans, and this scene positions the audience in an animal’s situation, as the monkey reacts similarly to how humans might: shivering, holding its hand over its eyes, and rocking back and forth. The monkey interrupts the narrative to remind us that whilst Rowf and Snitter have escaped, there are still animals that remain inside.

The film displays how animals fit into an anthropocentric world, many of which are in the service of humans.There are hunting dogs to help find Rowf and Snitter, dogs that herd sheep, animals in the testing centre, and chickens used for food. Since Rowf and Snitter identify as neither domestic nor wild, they have no position within the human world. Once the dogs escape the centre, the frequent canted and bird’s eye view shots suggest their unfamiliarity and powerlessness in the wild, and Rowf suggests that he and Snitter need to change to ensure their survival. When Snitter asks: “change to what?” Rowf replies: “To what we used to be; Real animals. Wild animals.” But what does Rowf mean by ‘we’? It is revealed that Snitter used to have a master, whereas it is indicated that Rowf was always a lab animal; neither of them were ever wild. So when Rowf says ‘we’, he appears to be referring to dogs in general.

There are two versions of The Plague Dogs: the 86 minute cut version, and the full 103 minute version. One scene taken from the book, in which a hired gunman falls to his death while attempting to shoot the dogs was removed from the cut version due to its shocking content. The spot light from a hovering helicopter shines down upon the body, to reveal that he has been mauled, implying that the dogs have eaten it in their struggle for survival. This savage behaviour subverts the idea of ‘man’s best friend’, which is perhaps one of the reasons the scene was cut, because it destroys the idea of a stable relationship between man and dog.

There is no place for Rowf and Snitter in a world controlled by humans, fleeing those who hunt them down. Once they reach the ocean they swim out into the open to avoid being shot. A bird’s eye angle reveals they are surrounded by water, suggesting there is no escape as the dogs appear tiny in comparison to the ocean. Upon first escaping the testing centre, a point of view shot shows Snitter looking at the stars as he says: “We’re free”. Now, he could not be any further from the glittering stars and the freedom they represent as he struggles to stay above the water. The film both begins and ends in water, framing the narrative to create a sense of entrapment; except now when they sink there will be no one to lift them out.

Snitter and Rowf escaping into the ocean

Rosen’s other film, Watership Down[4], also follows a story about the struggle for survival. The rabbits in Watership Down are victim to the natural world, whereas Rowf and Snitter are victim to the industrialised human world. Both films are adaptations from the novels of Richard Adams, carrying strong political messages surrounding the animal world. The Plague Dogs exposes the selfishness of the human world through this corrupt relationship between man and animal. Once the dogs present a threat to the human world their death is inevitable in a society controlled by man. As the dogs try to become more ‘wild’ in order to survive the harsh outdoors, it is revealed that, actually, it is they who are the more humane ones.

[1] The Plague Dogs. Dir. Martin Rosen. United Artists, 1982.

[2] Rob O’Neill, ‘Emerging Congruence between Animation and Anatomy’, Leonardo, 40 (2007) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/20206379 > [accessed 2nd January 2015] (p.169).

[3] Stephen Paget, Experiments on Animals, (New York: William Wood & Company, 1900), pp.158-159.

[4] Watership Down. Dir. Martin Rosen . CIC, 1978.

Further reading: Testing for humanity – The Plague Dogs revisited: https://www.quarterly-review.org/?p=2745

Bibliography

O’Neill, Rob, ‘Emerging Congruence between Animation and Anatomy’, Leonardo, 40.2 (2007) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/20206379 > [accessed 2nd January 2015]

Paget, Stephen, Experiments on Animals, (New York: William Wood & Company, 1900), pp.158-159.

The Plague Dogs. Dir. Martin Rosen. United Artists, 1982.

Watership Down. Dir. Martin Rosen. CIC, 1978.