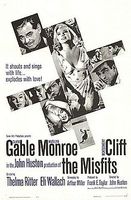

The Misfits (dir. Arthur Miller, 1961)

The final two scenes in The Misfits (dir. Arthur Miller, 1961) epitomise the varied conflicts that underpin the changing zeitgeist narrative of the film.[1] The relationship between the bucking beast and the faded hunter is complex; the mustang and the cowboy are two of the most poignant and pervading symbols of the Old West. Miller’s Mustang is both Gay’s adversary and Gay’s reflection; both belong to dying breeds threatened by the far reaching tentacle of the urban octopus, the highway, and the inexorable, ignoble and socially-integrated realities of modern wage labour. The aged and fading Gay wrestles the lone mustang and, now devoid of the trappings that have facilitated his trapping, is dragged kicking and grimacing along the ground. His struggle is symbolic and metaphorical; the final confrontation and release embodies the pride that has prevented Gay from embracing an ever-changing world being overcome as Gay is literally dragged, kicking and screaming, towards modernity.

Miller creates a scene that resembles a primal battle. The mechanised aids that have themselves usurped the horses and bastardised the act of capturing the mustangs are held off by their riders. By stripping away the symbols of Americana and modernity Miller imbues the last hurrah with a newfound sense of fairness. At this point both Gay and the Mustang are presented as animals; the repetitiveness of the scene, with the balance of power tipping back and forth, adds a dancelike quality and points to the symbiotic relationship between man and beast. Miller’s cinematography is relatively simple; the aerial shots are out and a series of static shots are used to emphasise the ebb and flow of the battle by stressing the kinetic energy of the horse and hunter. The dramatic crescendo of bass drums is reminiscent of a death scene, perhaps an execution, but the horse is spared from its modern, mechanised, meat-factory fate.

The co-dependency emphasised by the scene runs deep, the mustang trade had, in the past, enriched the cowboys financially and served as a centrepiece to their cultural experiences. In the final scene Gay denounces his corrupted livelihood. He laments the state of not only the mustang trade but also this way of life as a whole: ‘They changed it, changed it all around. Smeared it all over with blood’. Gay’s rolling-stone cowboy way of life is compromised but rather than being left – as per Dylan – with no direction home Gay is tempered by Roslyn. The promise of children looms on the horizon and another parallel is drawn, between the mustangs and their foal and the family that drives Gay and Roslyn’s aspirations. The viewer is left wondering whether the cowboy, like the horse, was not truly wild but more feral after all. Gay’s final instruction is to ‘Just head for that big star straight on. The highway’s under it – it’ll take us right home’. Three years later the same highway would be reclaimed by a whole new type of mustang, a cheap but showy commodity for the wage-labourers. Ironically the symbolism of the mustang itself had, again, gone Hollywood.

Bibliography

Miller, A. (dir) The Misfits, United Artists, 1961.

[1] The Misfits, dir. Arthur Miller. United Artists, 1961.