Human ignorance towards carnivorous eating behaviours are challenged in the ‘Les Poissons’ scene of The Little Mermaid, where a flamboyant chef sings about cooking fish as he prepares them.

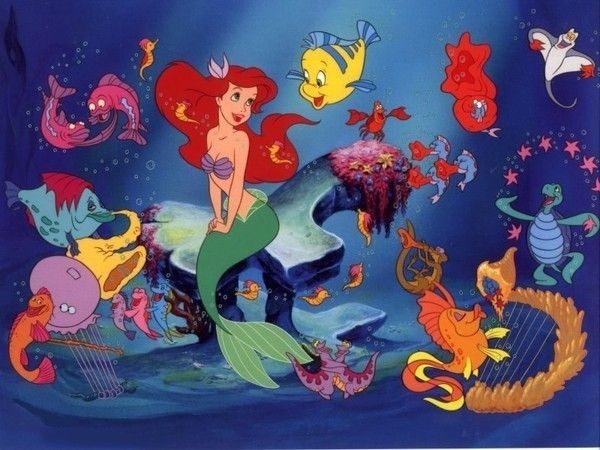

One example is through the physical appearance of the fish. Unlike the individualised, colourful and characterised animals in the rest of the film, the fish to be cooked and eaten are all identical and far less vibrant (not dissimilar to the rows of filleted, packaged fish we see on the shelves of supermarkets). This highlights their difference to those previously seen; their purpose for being on screen is to represent food, not characters.

Fig. 1: Characterised and diverse anthropomorphic sea creatures…

Fig. 2: … Identical looking fish for human consumption

The chef’s costume is exaggerated in its size; his moustache extends comically far away from his face and large mouth, and his toque blanche and red necktie also appear oversized. This helps present him as farcical and over-the-top, making his character comical in order to appeal to the young audience the film is intended for. Being seen as comical in his physicality (his moustache is wider than the bowl held in fig. 2; I’ve measured) emphasises the distractions we face regarding carnivorous eating. The chef shows human superiority over the animals in this situation through sizing, which we read as funny. The comedy helps us to forget the ethical questions surrounding meat-eating, thus highlighting the cultural ignorance we have adapted regarding eating animals.

We see the pleasure on his face at the prospect of eating them, emphasised by his focus on taste, for example: “tempting the palate,” “makes it taste nice.” These visual and verbal cues associate with our human understanding of eating fish, and the distance we have from it. By being cooked by the chef, the diner will simply see it as food, disassociating it with its animal form. This phenomenon identifies our general ignorance as humans when presented with animals as food, and our tendency to overlook that the flesh we are eating once belonged to a living animal.

Fig. 3: The cooked plate of fish for the human to eat, no longer resembling an animal (the whole fish).

The shots of preparation are mild in terms of goriness, in consideration of the family-intended audience. However, the way in which the chef interacts with the fish can be read as mildly sinister, despite also having comedic effect. In addition to his personal oversizing, the excessively large cleaver the chef uses is repeatedly shown in shots for humour and distress.

Fig. 4 Fig. 5 Fig. 6

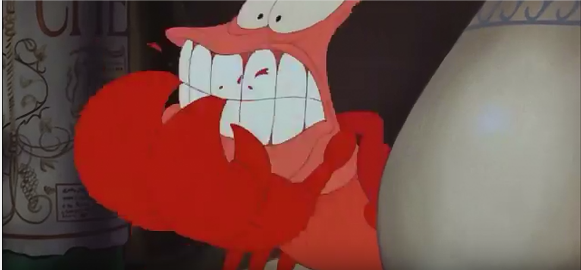

The distress we experience is through our emotive connection with Sebastian; the protagonist/hero, and only anthropomorphised animal of the scene. Because the film has already made us recognise and sympathise with him as a character we are led to imitate his reactions. The suspense of whether Sebastian will escape is what challenges the audience’s perception of animals as food. Seeing his fear and disgust encourages us to share his feelings regarding the situation, but because his reactions are so exaggerated (such as his eyes physically turning green to suggest nausea), we read his actions as comedic. The farcical nature of singing and exaggerated sizes and movements (such as Sebastian bouncing off the work-surface when the cleaver hits it), and the fact that Sebastian escapes unscathed, also keeps the scene light-hearted, again returning us to the blissful ignorance and lack of disgust when considering animal consumption.

Fig. 7: Feigning vomiting Fig. 8: Biting the tips of his claws (signifying the recognisable anxious human act of nail biting).

The chef’s comparative size is most apparent during the use of a silhouette shot. This technique removes all but the chef’s outline, intentionally retaining his smile, showing delight at having removed the fish’s internal mass. This shot is particularly sinister; the use of the three-pronged fork and a pointed chin resemble a devil-like figure victoriously brandishing the flesh of a fish, whose lifelessness is made apparent by its sloping tail and limp figure. By using only shadow the human and animal’s features are hidden, becoming anonymous. The anonymity of the chef and the animal reiterates the ignorance we tend to evoke when it comes to carnivorous eating; by not seeing features we are not seeing identity, therefore not considering the animals we are choosing to eat.

Fig. 9: Suggestive of the ‘damsel in distress’ trope

Because the film has already made us recognise and sympathise with anthropomorphised sea life, we are more likely to have emotive reactions towards the idea of fish being killed, cooked and eaten. However, we are still forced to somewhat overlook the ethics surrounding the consumption of animals through the use of comedy. By being presented with images to make us laugh, and our relief of Sebastian’s escape, we are lulled to forget the fish used as food in the scene, thus returning to an ignorant state of carnivorousness.