Jon Favreau’s 2019 recreation of The Lion King is something David Attenborough would be proud of, or is it? Disney seems to have a habit of reproducing the same stories, and after 25 years that’s just what they did with their animated animal take on Hamlet. Favreau’s CGI Lion King tells the story of a young cub (Simba) as he finds his place in the circle of life. Hindering him are the actions of his sly uncle (Scar) who kills Mufasa, his own brother and Simba’s father, to take the throne, he desired all his life. Simba does what any young adult in his position would do, joins a group of hippy free-living friends in the jungle. That is until his love interest (and potential cousin) Nala reminds him of his responsibilities, and he receives a visit from Rafiki, the mandrill Sharman of the pride lands, who guides Simba spiritually to his father. Eventually Simba returns to take back his throne and his responsibility in the circle of life. Oh, and did I mention? He’s a lion!

The Lion King is both a family film and a wildlife film all in one, but what Favreau does to the story through the combination of CGI and use of a more gritty, realistic visual presentation of animals changes the film from simply being a family film grounded in Shakespearean story tropes to a darker satire of the revenge plot. Typically, the family film presents a journey of growing up and a lesson learned or childhood to adulthood development, with the entertainment value coming from music and bright colours as well as humour that appeals to young and old, to keep the audience watching. With The Lion king, the story shows Simba overcoming the naivety of youth to become a strong leader of the pride. It also has the wildlife element from the realistic visuals where you can see every single hair on the lions back, even when setting the scenes Favreau used new augmented reality technology to see these CGI animals in the real environment, blurring the line between the film being a fictional story and a presentation of these animals in their natural habitat.

Figure 1 Simba’s emotion meme

Figure 2 using AR and a real lion’s movement’s for comparison in production for the Lion King.

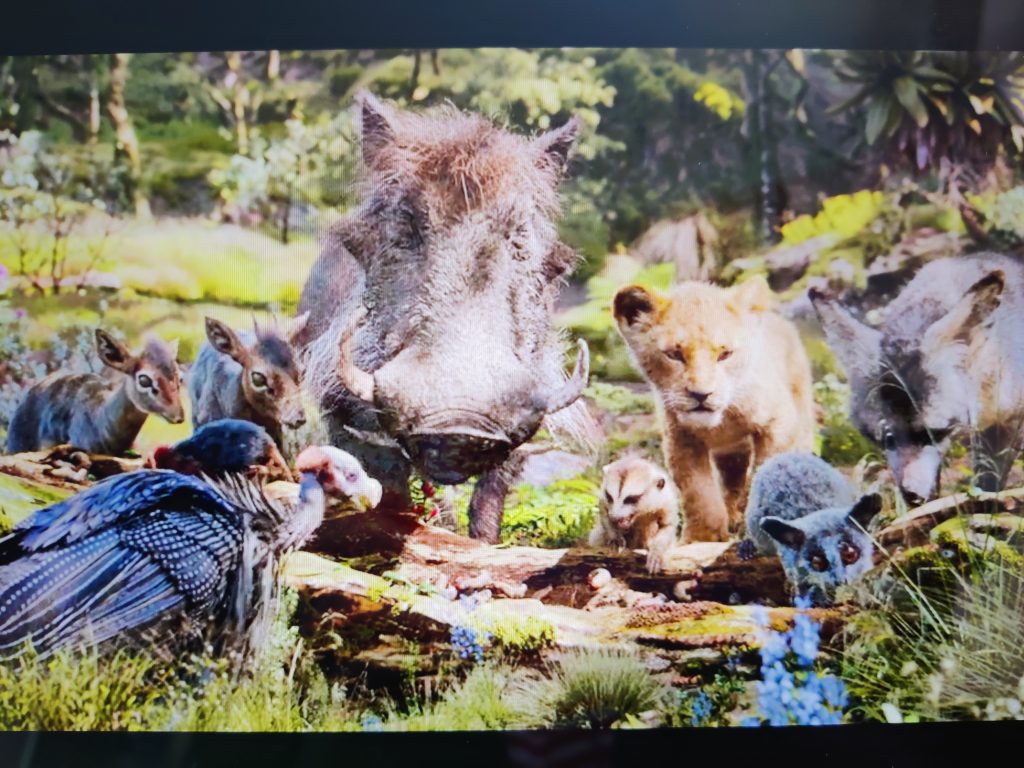

Simba’s naivety and understanding of ‘how the world works’ plays into the genre, however the problem arises when you use a lion. In the wild, male lions tend to leave their home pride and go in search of another of their own. To some extent this is reflected in the story as Simba does leave as a cub and finds his own family, but not in the world of lions, he instead finds a warthog, a meerkat, and a whole host of other animals living in the jungle. The striking image of what appears to be a real lion in the jungle amongst these, mainly omnivorous, creatures’ contrasts with what actual animal behaviour would be like, by making all these animals look so real – to the extent that in this image below it almost looks like a bad joke.

Figure 3 Minute 57 of The Lion King, Simba with a variety of would-be prey

The problem with him being shown as an equal, socially, with these other animals is exasperated by how the whole story is driven on his sense of responsibility and the idea that he must take his place in the ‘circle of life’. As a wild animal he does have a place in the food chain where he fits in, and this removes him from the anthropomorphised hippy, free living, lion in the jungle with Pumba and Timone’s ideology that they live on a line of indifference. Therefore, there is an issue with the plot. How can he be both an accurate presentation of a male lion as well as having these interactions and familiarities with other animals, and why does he need to follow this strictly set out purpose and role – if ‘hakuna matata’ means no worries, is that something he isn’t allowed to have? The film appears to deal with this problem by using his position as royalty to separate him from the rest of the animals; as the apex predator he is king, in charge of ensuring the balance of life. This is shown in contrast to the hyenas who are portrayed as having no respect and killing whatever they come across, when in fact they are mostly scavengers who eat what is already dead and are therefore vital in the ecosystem of Africa. Instead, here their purpose in the story is as Scar’s dogsbodies, but they ultimately return to a more vicious state at the end when they kill Scar. The film uses their stereotype as a dangerous but mindless predator to give them the more human role of a foot soldier. From an educational point of view, the fact that he is given the same courtesies as a human member of royalty is unrealistic. Lions are considered royalty by certain cultures because of their raw power and strength which makes them the apex predator, placing them on a pedestal above the other animals. However, this royalty is translated in the film differently to the real world as he is treated well, not because the other animals fear him, but because they respect him. This presents Lion’s as a regal creature rather than revered for their sheer physical dominance, which you can see in Mufasa, particularly when he saves Simba and Nala from the hyenas, as he himself says he only fight’s when he has too.

A particularly interesting use of the wildlife documentary style of filming, captured in this scene with Mufasa and the Hyenas, is the journey of one of Simba’s hairs to Rafiki. Expanding on the animation’s take, this journey last’s minutes and uses the cinematography to present it in a beautiful and sublime way. The combination of colours and light with the fluid motion of the camera and the music, which seems to match the size and pace of the animal’s movements, makes the scene appear as if it’s one shot before pausing as the camera visits the dung beetles, which enhances the impact of the animals as they appear to stop both the hair, and the camera in its tracks. This makes it feel more realistic as it shows the animals eating and going about their daily life separate from the story. In addition, through showing this large variety of animals, it makes the plot not just about one lion but an entire ecosystem, therefore highlighting the importance of animal-animal relations as you can clearly see how one affects the other. For example, when we see the tiny dung beetles rolling the giraffe dung containing one of Simba’s hairs, this is a typical behaviour and therefore adds to the realism, even if it is mostly down to CGI – this would have been filmed and then edited to show the hair. This element is added to the film to present more of the animal kingdom as John Favreau wanted to expand on the “naturalism of that world”[i][1], by showing more animals it fleshes out the world of the movie and presents a realistic depiction. Whether this was a good idea comes down to how it was received whilst missing the human face that audiences could relate to in the CGI Jungle Book that came before it. That is where the wildlife element comes in to add some moments of education and spectacle that draws so many viewers to shows like Blue planet, for this sequence isn’t the only shot that follows animals outside of the main plot. There is also the short scene at the start of the film following the shrew on its little journey to the end of a plant where we then see Scar come into full view. The purpose of the attention to detail in these extra scenes blends the story with the real world and the entire animal kingdom, rather than just being a human story in the animal world. It shows how this feeds in to ‘the circle of life’: the small shrew, with the big lion; the single lion hair through all the creatures to Rafiki. Which brings us too why, despite some audiences struggling with the lack of ‘human’ expressions of emotion on the animals faces, the film was still enjoyed by many for its clever and beautiful presentation of animals. Is it then a problem if people separate the story from the cinematography?

Figure 4 A life on our planet David Attenborough from Netflix 2021, watch the first two minutes of this video it shows how we view these lands as a sublime spectacle visually which Favreau clearly tries to emulate.

The answer is no, ultimately, it’s the gritty realism of the film that enables veiwers to not loose sight of the plot when combined with these beautiful shots of animals in their natural habitat. For instance, when Scar appears from the darkness to face the shrew on the end of the stem, his face is made to look menacing, through his name’s sake scars and dark and dishevelled looking hair. Favreau heightens this with the deep and mature voice of Chiwetel Ejiofor, Scar is characterised not just as a vengeful uncle but a lion that doesn’t have what it takes to be a king. He physically lacks the strength and muscle, which is highlighted when we see his full body come into the light next to Mufasa as a stark contrast – it makes it appear impossible for him to fight his brother alone. Scar takes on the traits of a human man who is too weak to ever get his own hands dirty, whilst having the brains to overcome the obstacles (Simba) in his way. If this film kept the less fleshed out and extremely child friendly elements of the original animation with this realistic CGI it would have been far from a true telling of animal-animal relations, or at least a human perception of them. By adding details such as; the changes in Scar’s musical number, shorter and largely spoken to the ominous hum of the music rather than sung upbeat; his attitude towards Simba’s mother, being much more romantic throughout the film and his character being given very little comic relief, it develops his characterisation as a lion and a poor leader. Whilst doing this it helps to depict the harsh realities of the animal kingdom, through the idea that Sarabi would essentially belong to Scar when he leads the pride. However, Favreau seems to suggest she has a choice in this matter and stands her own ground, which I would argue is because human audiences would struggle to relate to such an instant change of heart. Even though this behaviour is more human than animal, the problem is navigated by the idea that Scar is in fact the improper lion since he works with Hyenas and has ruined the pride lands, which makes his behaviour less true to his animal self. Nevertheless, the darkness of the story appears to enhance its realism, the moment all audience members dreaded was a young Simba going up to his fathers dead and lifeless body, yet this is not uncommon in the animal world, even Mufasa suggests to Scar that he would die before him because that seems to be what happens in the circle of life, rather than the line of indifference.

The portrayal of animal society mixing with CGI within the Lion King reflects a reading of animal-animal relations as being vital. This is done through combining the importance of a balanced eco-system in the circle of life and the humanisation of friendships across species to ensure the circle continues. In addition, what this film does by enhancing the realism and grit of both the plot and the visuals allows it to present the animals in a way that is both relatable to a human audience and close to an accurate portrayal of wild animal’s movements and behaviours.

Figure 5 Zootropolis 2016, image of working animals including a fat lazy cheetah and an overbearing looking buffalo for a police chief.

Figure 6 A Shark Tale image of a real great white shark above the animated one from the film with his friend Oscar who is a fish.

To finish, the 2019 Lion King develops our understanding of human-animal relations by its choice of which elements to humanise, emotionally and socially, and which to portray more accurately. By using CGI Favreau brought us into the animal world and its day-to-day struggles, not just those of the lions but of the shrews, giraffes and all manner of creatures living in the pride lands. Unlike films like Zootropolis and Shark Tale, it doesn’t just focus on the stereotypes of certain animals to characterise them. Instead reflect where they exist in the ecosystem and how a human story of revenge and growing up can be just as relevant to this world through the darkness of the storyline reflecting animal behaviours that humans may find uncomfortable, such as Sarabi moving onto be Scar’s queen.

References

Libbey, Dirk, ‘Jon Favreau reveals what inspired him to remake the lion king’, Cinemablend, 30 July 2019 < Jon Favreau Reveals What Inspired Him To Remake The Lion King | Cinemablend > [accessed 8 January 2022]

Further Reading

[1] Woloski, Sarah, ‘The Lion King 2019: four fascinating behind the scenes stories’, Sky walking through Neverland <THE LION KING 2019: Four Fascinating Behind-The-Scenes Stories – Skywalking Network (skywalkingthroughneverland.com) >

[2] Big Movies behind the scenes, The Lion King 2019 behind the scenes production material, online video, YouTube, 13 August 2020 < The Lion King 2019 Behind The Scenes Production Material – YouTube >

[3] Radulovic, Petrana, ‘Are Simba and Nala related? A lion expert weighs in’, Polygon <Are Simba and Nala related? A lion expert weighs in – Polygon >

[4] Callari, Ron, ‘How do real animals differ from the anthropomorphic ones in the ‘lion king’?’, Pets lady <How Do Real Animals Differ From The Anthropomorphic Ones In The ‘Lion King’? | Petslady.com>

[5] Cavna, Michael, ‘Lion King Remake Blurs the Lines on Live Action; Simba Stirs up Movie Fans over CGI Animation’, National Post (Toronto) (Don Mills, Ont: Postmedia Network Inc, 2018)

Bibliography

Africa (BBC, 2013) < BBC One – Africa, The Greatest Show on Earth> [accessed 11 January 2022]

Bousé, Derek, ‘The Classic Model’ in Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), pp. 127-151

Cavna, Michael ‘Lion King Remake Blurs the Lines on Live Action; Simba Stirs up Movie Fans over CGI Animation’, National Post (Toronto) (Don Mills, Ont: Postmedia Network Inc, 2018) [accessed 11 January 2022]

Favreau, Jon, dir., The Lion King (Walt Disney Pictures and Fairview entertainment 2019)

Howard, Byron. Moore Riche, dir., Zootropolis (Walt Disney Pictures, 2016)

Lehmann, Monika B, Paul J Funston, Cailey R Owen, and Rob Slotow, ‘Home Range Utilisation and Territorial Behaviour of Lions (Panthera Leo) on Karongwe Game Reserve, South Africa’, PloS One, 3.12 (2008), e3998–e3998

Letterman, Rob. Bergeron, Bob. Jenson, Vicky, dir., Shark Tale (DreamWorks pictures, 2004)

Radulovic, Petrana, ‘Are Simba and Nala related? A lion expert weighs in’, Polygon <Are Simba and Nala related? A lion expert weighs in – Polygon > [accessed 10 January 2022]

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008), pp. 18-59

[i] Dirk Libbey, ‘Jon Favreau reveals what inspired him to remake the lion king’, Cinemablend, 30 July 2019 < Jon Favreau Reveals What Inspired Him To Remake The Lion King | Cinemablend > [accessed 8 January 2022].