The Fox and the Hound (1981) revolves around an orphaned red fox named Tod (Mickey Rooney) who befriends a young hound puppy, Copper (Kurt Russell). The two grow very fond of one another, despite their natural born differences, although their human owners Slade (Jack Albertson) and Tweed (Jeanette Nolan) do not share the same friendliness. Tod and Copper are natural born enemies and are pitted against one another, which is exacerbated by the tensions between their owners. When Tweed realises Tod is no longer safe with her, she leaves him in the wild to which he adapts with the help of a female fox named Vixey (Sandy Duncan). As both Tod and Copper reach adulthood, they have inevitably grown apart due to their roles within the animal kingdom and Copper being bred as a hunting dog. Tod and Copper display human characteristics throughout the film, for instance forgiveness and heightened emotions, but they also have tendencies to show their natural animal-like wildness too. The film is nostalgic and heart-wrenching, sending a moral message surrounding friendship and born-differences. This Disney classic teaches valuable lessons whilst blurring the ethical lines by exploring complex topics such as death, hunting and betrayal.

The Fox and the Hound is a children’s animated feature film, providing various sub-genres such as adventure, drama and family. The heart-warming tale resonates well with the young and family audiences who appreciate the sentimentality and entertainment that is affiliated with animals. This is expected of Hollywood Disney animated films, as to cater for younger audiences, the genre has to adhere to the theme of self-improvement and growth of characters, sending a moral message to the children. The anthropomorphism helps this genre unveil realism in terms of growing up and drifting apart in an entirely unrealistic way – by using animals who speak, befriend one another and understand/express emotions coherently. Within this film, we see the growth and consequently the separation of characters as they understand the sacrifices they must make in order to be what is expected of them. The high emotional states portrayed by the animals within the film, similar to their human owners, is a key component within the animated feature films and it is how the genre manages to tackle the darker, more complex topics situated within the film. However, a slight difference within The Fox and the Hound in comparison to other Disney animated feature films is the ending. Both Tod and Copper acknowledge one another but understand and accept why they cannot be ‘Best Friends Forever’ due to their positions within the animal kingdom. This poignant ending accentuates the reality within this animation, and how friends can grow apart without a miracle and unnatural reconciliation at the end.

As argued by Paul Wells, the use of animals within films helps tackle wider societal issues which would be problematic to address directly due to political or social restrictions[1]. These darker elements are engaged with thoroughly within The Fox and the Hound could possibly represent worries over recent wars and questioning how soldiers are willing to fight a group of people they have been taught to hate. These external forces which cause Tod and Copper to turn against one another, can be understood through the Hypodermic Needle theory presented by Stuart Hall which suggests audiences are injected with content to provide a desired response[2]. The moral message behind this film suggests we are not born hating someone because they are different to us, but rather we are taught, causing a reflection on our humanity as an audience.

There is a sad irony in the scene where Tod and Copper first meet. The first physical contact they have with one another is shown through a mid-shot of Copper’s nose reaching into Tod’s ear through a log on the forest floor. This very animal-like act of ‘sniffing’ Tod out is conforming to his hunting dog status, although Copper does not react in an aggressive or hateful way, this instead is something he is taught later on, reinforcing how hate is taught and not innate. The dialogue shared between the two strengthens this, as Copper reveals he does not know what he is trying to hunt or why, until he gets closer to Tod and then he realises, ‘Why it’s you’. The child-like voices used alongside the upbeat use of sound score suggests there is a sense of innocence and vulnerability between the two. The two share bittersweet moments, such as when they play hide and seek. This human-like behaviour is observed and commented on by the owl Big Mama (Pearl Bailey) who is shown from a behind the shoulder shot, overlooking them from above. Big Mama’s character is animalised, as she is depicted as wise and all-seeing, something which we automatically associate with owls. Big Mama’s voice is then heard singing over the shots of them playing hide and seek, which makes the whole scene feel very bittersweet, because as an audience we are aware that the two do not normally befriend one another, due to their different species. The mid shot which portrays Tod’s tail replacing Copper’s is comical, projecting an image of unity and foreshadowing the blossoming of friendship, despite their differences. Later in the scene, when Copper is being scolded by Slade, his ears droop, presenting us with a constructed trait we associate with animals as to when they feel unhappy or guilty.

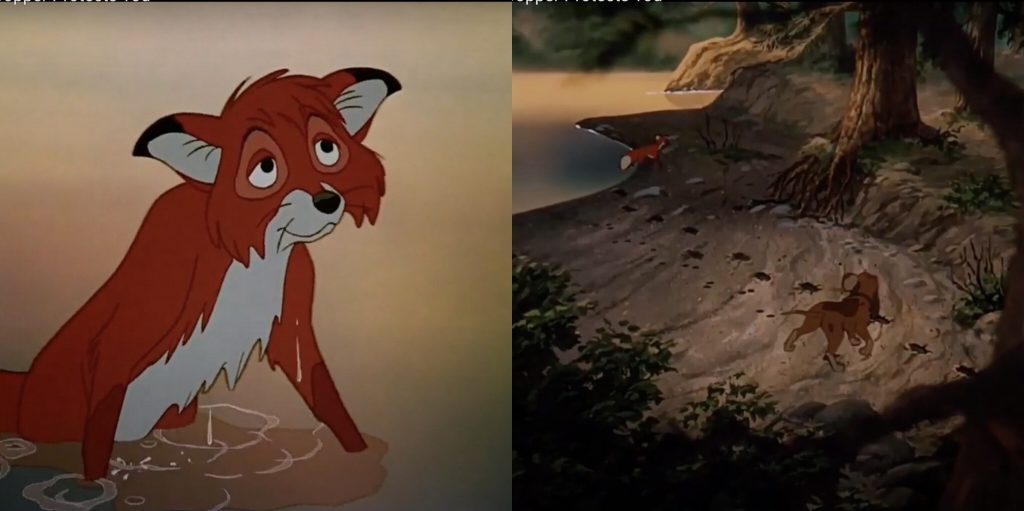

This next scene shows the degeneration of Tod and Copper’s friendship as there is no acknowledgement between the two of their previous bond. Rather what we see in this scene is pure instinctual savagery from both animals, as they fight one another to almost death. The foreshadowing of the events occurs at the beginning of the scene whereby Tod sanders ahead of Vixie to inspect the area where Slade is hiding, having set traps to catch Tod. The low lighting and the extra-diegetic sound score situates the audience in a tense position, as the tempo begins to increase and drums are used for dramatic effect. As Tod’s ears droop, a common association with animals when they are anxious, we know he is about to encounter trouble. The mid shot portraying Tod missing every trap laid out for him may hint to how foxes are known for their nimbleness, with their agility and fast-paced movements, or in Tod’s case, it appeared this was merely a stroke of luck.

As Tod and Copper begin to fight one another, we see how all previous friendship is utterly lost. With close ups of their sharp teeth and the fast-paced cuts which lay their snarling faces transparently over the image of the other, the emotions of anger and betrayal are prominent. The fighting shots provide the audience with hellish imagery, as a close-up reveals Tod with menacing red eyes, stressing the rage and resentment behind his motives. Later in the scene, this imagery is used again with the raging fire that engulfs Tod and Vixey’s home which consumes the screen in smoke and total darkness.

This relates to Rick Altman’s theory of genre and how by using synaptic elements, the audience can process emotions of the characters, therefore Tod’s red eyes in this scene represent how manic and destructive he is willing to be to protect his mate[3]. The intra-diegetic sounds of their whimpers and howls indicates how their wild animal has been unleashed, and how they have succumbed to their own savagery. Both animals are not represented as soft and necessarily ‘cute’ in reality, and this is emphasised in this scene which adheres to their actual stereotype of being stealthy and often aggressive.

This scene, which occurs towards the end of the film, reveals the power behind Copper and Tod’s bond, whilst also giving Slade redemption in his character. Within this scene, there are no words spoken between the two animals. The lack of dialogue represents how substantial their emotional connection is as we digest the emotions of forgiveness and regret which is unspoken on our screens. The initial wide shot of the beautiful landscape shows Tod, vibrantly emerging from the water, contrasting the blue misty colours within the shot. The animation and colours within this scene are of brilliant quality for its time and work very well to highlight Tod as the main focus.

h

h

The intimidating centre-frame close up of Slade with the barrel of his metal gun pointed directly at Tod provides a contrasting image with the green pine trees and natural landscape behind him. The landscape shown behind represents tranquillity and peace, which reinforces the irony here as Slade is so out of touch with all things natural. The coat Slade is wearing within this shot has a fur trim collar, something which we can infer is real fur from an animal he has hunted and slaughtered. This imagery is disturbing and further paints Slade, the human, as the villain within the film.

The mid shot of Copper defending Tod, as his body shields him from Slade, reveals Tod expressing a human-like emotion of surprise and worry. This is another example of anthropomorphism as this facial expression and emotion is not one usually depicted so clearly on an animal’s face. The actions that occur here show us that these animals are capable of understanding and expressing human emotions such as forgiveness and sympathy. Copper and Slade share a moment within this scene, as Copper whimpers at Slade and gives his continued eye contact. This unsaid connection between human and dog causes Slade to realise that he has to accept Tod and Copper’s bond, despite their differences and how he was wrong to interfere so incessantly. The extra-diegetic piano playing in the background whilst Copper follows Slade home provides an emotional farewell between the two animals. Tod’s facial expression changes again, but this time to a smile which then cuts to Copper who mimics the same smile. The camera then pans out to show Copper leaving Tod in the water, with the pleasant knowledge that he has just successfully saved his best friend. The two share one more affectionate look with one another, just as the camera fades to black.

The representation of animals within The Fox and the Hound stresses how easy it is to be taught hate, and suffer prejudice, despite your species. By using two animals who are born to be natural enemies and producing a beautifully animated friendship, which is only torn apart by external forces, Disney projects an image of wider society. By using animals, the falling apart of friendship can be seen happening across a smaller time frame, as they grow into adulthood faster than humans, thus we can see how quickly the process of life and loss occurs. When they are cubs they do not think about the future or how their attachment might have an impact on others, similarly to human children who befriend other children without acknowledgment of adulthood or the consequences it might bring. Then inevitability, just like with humans, ideas and prejudices are planted into their minds to fester and develop and that’s when friendships begin to fall apart. Thus, children can take away moral messages such as the inevitability of loss of friendships and reflect on the control they could potentially let society have on their lives.

This film presents heavy and complex topics which is usually not displayed within Disney films. However, due to the era this film was released, it can be interpreted as a post-war, anti-hate campaign which places the blame of the war onto those in power who are able to manipulate those beneath them to dislike those who are different, and therefore inferior, to themselves. The Fox and the Hound touches on the power of friendship over the expectations of others, whilst also promoting the benefits of new beginnings and initial loneliness. This film’s message is incredibly progressive and brings such a nostalgic vibe to our screens, rendering it a beautifully animated Disney classic.

h

Bibliography –

Altman, Rick, ‘A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre’, Cinema Journal 23.3 (1984), pp. 6-18.

Hall, Stuart, ‘Encoding/Decoding’ Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (London: Hutchinson, 1980).

The Fox and the Hound – Theatrical Trailer (2014) YouTube Video, added by The Disney Animation Resource Channel <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFwPyqQy9K0> [Accessed 20 December 2020].

Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (2008).

Wikia Entertainment, ‘The Fox and the Hound’, The Disney Wiki, <https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/The_Fox_and_the_Hound> [Accessed 01 January 2021].

h

Further Reading –

David Whitley, The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation (Hampshire: Routledge, 2008)

Giannaalberto Bendazzi, 100 Years of Cinema Animation (1994)

Entertainment, ‘I’m Still Not Over … Tod and Copper in ‘The Fox and the Hound’ ‘ <https://ew.com/article/2013/11/18/im-still-not-over-fox-and-the-hound/> [Accessed 05 January 2021].

h

[1] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (2008)

[2] Stuart Hall, ‘Encoding/Decoding’ Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (London: Hutchinson, 1980)

[3] Rick Altman, ‘A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre’, Cinema Journal 23.3 (1984)