Animals Articulating Emotion and Inspiring Growth in The Darjeeling Limited

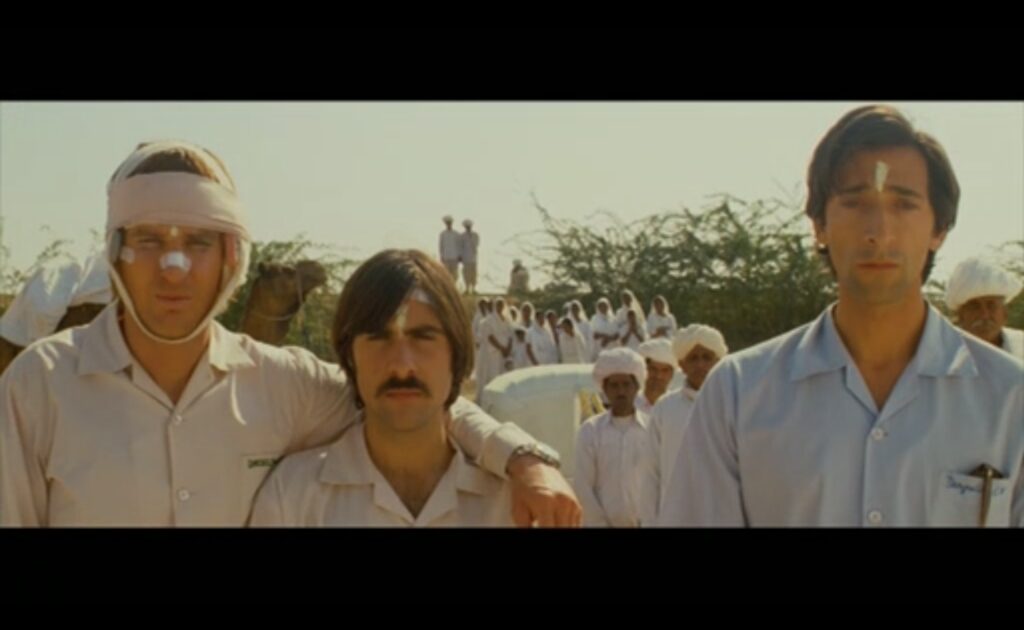

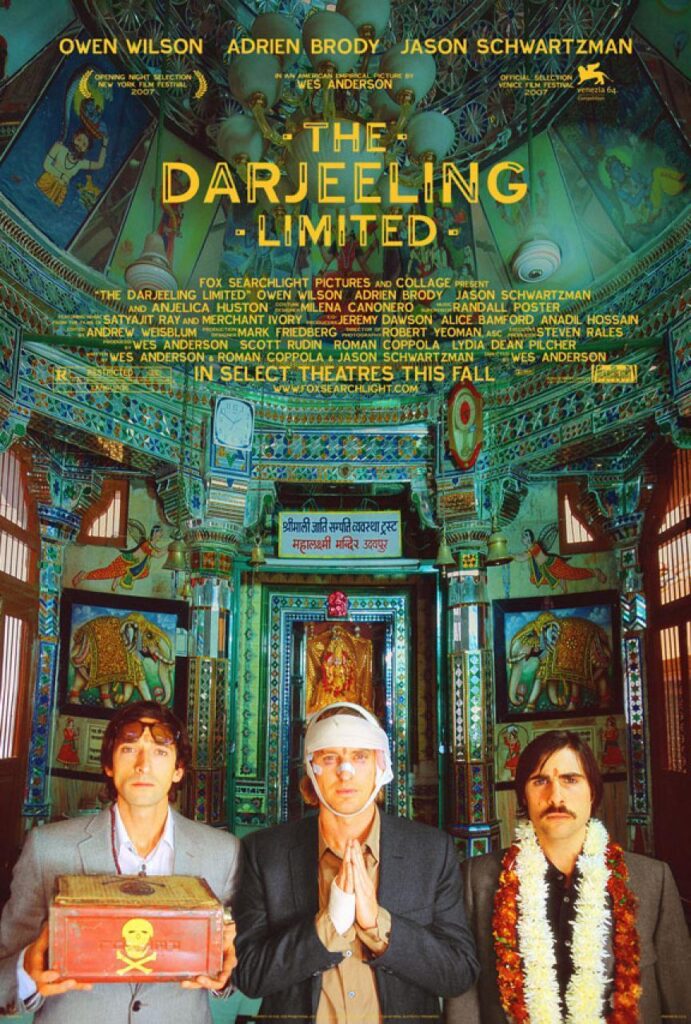

In an attempt to remedy their stagnant relationship, three brothers, Francis (Owen Wilson), Peter (Adrien Brody) and Jack (Jason Schwartzman) board a train travelling around India. Each brother harbours his own inner turmoil which contributes to the complex relationship between the brothers and is often articulated through shared glances, ludicrous behaviour and comedic outbursts. Wes Anderson does not however solely rely on his carefully designed characters to convey a textured, affective sibling relationship, but instead adopts animals to stimulate startling action and to communicate unconscious feeling and development. Anderson continuously steeps the brothers in animal imagery with his distinctive intricate designs which find new relevancy in the films setting as animal representations have an expansive and textured history in Indian culture. Animal imagery is visible throughout the film as demonstrated in this selection of images.

Despite this connection, the film leans largely on the rich setting purely for visual pleasure, with its characters restraining from any divulgence into the culture with any great depth. Anderson’s commitment to meticulous detail encourages our consideration of each item in the frame and The Darjeeling Limited plays on and occasionally rewards our curiosity. Anderson accentuates specific animal representations to pierce through the prevalence of animal imagery which neatly suits the narrative importance of the unpredictable and the progression that it inspires in the film.

The foundation of the film is the forced spiritual journey enforced by Francis in an attempt to connect with his recently estranged brothers, but it is in its failure and resulting unpredictability that the chaotic humour and tender reflections can bloom. One of the major catalysts for this affective development is the snake which is purchased by Peter on a whim at a market. Anderson leads us to the snake via a panning shot which rises away from Jack who is mid-conversation about purchasing mace which will later enable a memorable, hilarious scene, and up to an upper-level stall which is covered in illustrated signs for various animals, most strikingly, snakes. This pan away conveys a sense of distraction as though the animal stall has eclipsed our attention despite the looming relevancy of the mace and teases a potentially riveting animal-based scene. The cobra is introduced in captivity, contained in a small glass box padded with sand.

Interestingly, the cobra is partly risen with its hood extended outwards, a typical defensive pose which aims to create a more domineering image when the snake is feeling threatened. The pose is targeted directly towards the audience in the classically enticing bright rectangular frame, placing us on the same level as the cobra as opposed to the brothers who loom over the snake, receiving a different perspective and cementing Peters decision to own the snake.

Beyond this visual communication, mixed loudly in this scene is a hiss, further indicating that the cobra is feeling highly defensive. This display of menace rouses the viewer to view the snake as volatile, developed by the snake keepers brief run down on the snake, ‘Most rare. From desert. Very poisonous.’. If this narrative is stripped back, the snake is quite tragically framed, restricted to a box no longer than its body, on sale without the appropriate screening and passed over to a man who does not appear to provide the necessities for its survival (the inside of his travel box contains lettuce leaves despite the cobras carnivorous, no visible source of water and a complete lack of padding). Ironically, when acquiring a snake to cast for this role, Anderson selected a cobra as opposed to his desired, ‘little, red, spectacularly poisonous species called a Krait’ due to its availability, commenting that, ‘The most readily available snakes in Rajasthan seem to be cobras.’.

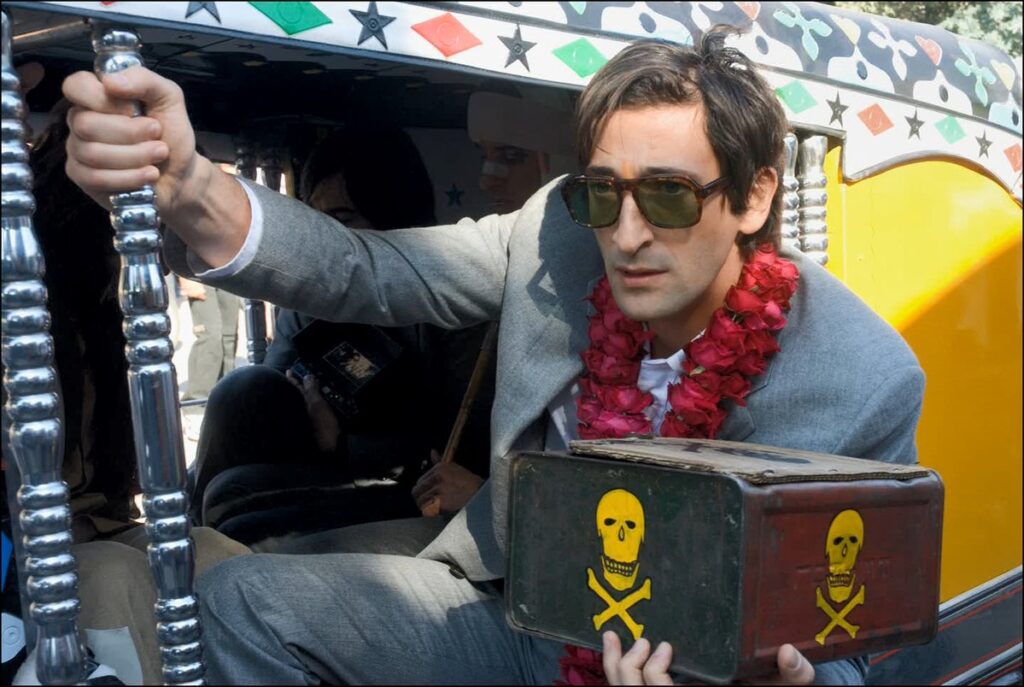

Perhaps the contradictory label of rarity is intended to be a sales technique by the seller, however it is unlikely that the viewer is particularly aware of this specific snake population and their availability on the market. More likely, Anderson is weaving a narrative which communicates Peter’s desires to own a potentially deadly, independent and therefor threatening serpent which may work to deter people from approaching him. Peter is often pensive, articulating astute reflections on his and his brothers’ behavioural patterns which are frequently eclipsed by Francis. Peter purchases the snake in haste and does not appear to receive any instruction on how to care for the cobra which may have stifled the humour in the spontaneity and, likely, irresponsibility. Peter boards the train with the boxed snake, sparking confusion in Francis’ assistant Brendan (Wallace Wolodarsky) who points out the skull and crossbones emblazoned on the meagre box.

With this small remark, Brendan provides a neutral, relatable voice which accentuates the absurdity of the situation. Here the snake is again defined by its danger, the cobra is death. Peter is most explicitly mournful over his father’s passing, lamenting via his adornment in his father’s clothes and expressing his sense of closeness to his father by provocative statements of favouritism. Peter, in his ownership of the snake, and more crucially, the reputation following it, could be seen to be the owner of death, finding power in the physical containment of it. Regardless of efforts to uncover Peter’s motivation in buying the cobra, the act is overwhelmingly random and leads to the endangerment of the enter population of the train as it somehow escapes. Peter awakes and claims that the snake has escaped, immediately shifting the snake from an extreme tool for Peter to grapple with death, to a terrifying independent threat.

The unlikely, destructive escape of the snake mirrors the often-unbelievable shock of death, similarly the brothers’ immediate refusal and inability to capture the snake, instead panicking, reveals their dependence on outside sources to solve their problems. The capable chief steward (Waris Ahluwalia) captures the cobra and banishes it from the train, before discovering the extent of the chaos surrounding the brothers in their messy cabin littered with various prescription drugs. The heavy abuse of prescription drugs amongst the three brothers could provide an alternative context for the acquisition of the Indian cobra which grows in favour with Francis as the film develops. The venom of the young Indian cobra can be illegally acquired for recreational substance abuse, but it is also often sustained through a provoked bite- this form of abuse can result in fatality or serious illness. This could explain the mysterious motivation to purchase the poisonous snake, promoting Anderson’s intentional detailing and encouraging our curiosity. The significance of the cobra is furthered by its prominence in the official film poster, the skull and crossbone symbol works to easily communicate death and danger, immediately sparking interest and communicating the importance of the snake in relation to Peter.

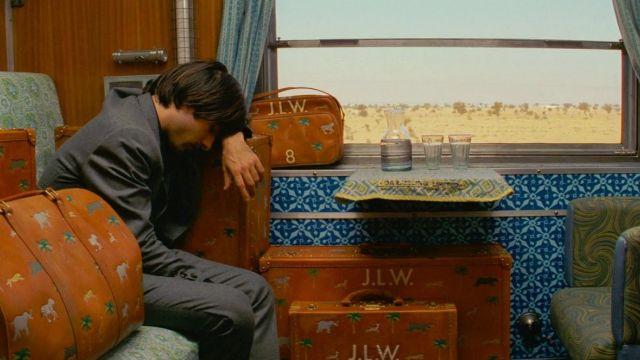

Undeniably characterful, and later reproduced for sale amongst its admirers, is the Whitman’s luggage.

The luggage remains monogrammed from its previous owner, the late father of the Whitman brother’s, and features palm trees and a variety of typically ‘exotic’ animals, from zebras to gazelles. This typical vacation themed print characterises the otherwise unseen father, the original force that inspired Francis to call his brothers together for the journey on The Darjeeling Limited train. The extensive range of luggage indicates that the father was a committed traveller with animals such as the elephant and giraffe evoking idealistic images of Asia and Africa as potential travel destinations, warmed against the hazelnut brown leather. Similarly idealistic, Francis as the eldest brother, takes it upon himself to hire another man, Brendan, to heavily plan a ‘spiritual journey’ on which he wishes his brothers will bond and heal from their complex wounds. This plan proves to be ineffective, reflecting the tone of idealism and choreographed growth as a hindrance to personal and relational development. The luggage remains with the brothers through challenging situations, as they lug it along roads, check it into a flight and beyond, until the film begins to near its optimistic conclusion. After pushing through their (often self-inflicted) chaos and stripping away their pretences, the brothers reconvene to board The Darjeeling Limited in a sequence which mirrors the opening of the film. This time, the brothers must abandon their father’s baggage in order to carry on their journey together, which delivers satisfying, yet simplistic symbolism. Of course, as this is a Wes Anderson film, the additional funky animal imagery deepens the emotional field by communicating that Francis must also release the romanticised idea of tightly structured journeys and accept that he has been restricting his own and his brother’s growth in organic experience by trying to follow a linear, clinical journey.

Finally, Anderson introduces a new threat to the human characters via a rumoured escaped tiger which has claimed victims in the area where the brothers mother is living. She advises the brothers against visiting her partly due to the threat imposed by the animal, however they believe it to be a ludicrous attempt at preventing them from visiting and defy her advice. Here, the tiger raises the vivid disconnection between the brothers and their mother as they evidence their immunity to preposterous lies as a distancing mechanism.The brothers continue to disbelieve the rumours, finding humour in the tales of attacks, until they are presented with a track of large paw pads. Once again, Anderson relies on the potential for an animal to fatally attack a human through representative imagery rather than the physicality of the animal. The brothers are successful in their aim to stay with their mother, however as the screen is wiped with darkness to transition into the brothers in the convent, a growl is audible. This ominous sound design once again fires the imagination of the viewer just before they are plunged into a domestic scene as the three brothers sit before their mother in their nightwear bearing exhausted expressions.

The proximity of the growl from a potentially lethal tiger to this vulnerable scene creates a potent sense of uneasiness. Despite their growth, the brothers continue to seek comfort where they will not find it by gripping onto imagined, or past, realities. The determination of the men, and especially Francis, in their reconnection with their mother is overlayed by the unstable presence of the tiger. The tiger is imprinted in various scenes throughout the film, on the interior and exterior walls of The Darjeeling Limited for example, where it can be admired comfortably in its two-dimensional rendering. The tiger is transformed, echoing the cobra, when it cannot be contained and dominated by the human. In this light, the tiger challenges the human’s sense of control and certainty as the cobra did with the uncertainty of death. Anderson provides relief by dispelling the supposed threat by the omission of the tiger from the following narrative, allowing the brothers to accept and overcome their dilemmas by releasing their expectations and moving forwards, without fighting for control.

The Darjeeling Limited utilises animals and animal imagery to articulate otherwise stifled emotions and to trigger substantial shifts in the narrative with engaging detail. Anderson’s commitment to intricacy entices the audience to indulge in thoughtful consideration of striking features such as the curious adoption of a poisonous cobra. The snake is often obscured by its dismal travel box, plastered with threatening iconography which expresses potential death, an issue which shrouds Peter. Plagued also by their drug use, the cobra may hold a more ominous potential for the brothers which is terminated through its dramatic escape. Anderson also involves animals in the prominent luggage which accompanies the brothers on their journey, beginning as a romantic, endearing accessory and ending discarded along with its idealism. Finally, the tiger challenges the three brothers to realise that they will not find comfort in the convent in which they lie and should accept and move away from their final ideal.

Primary Source

The Darjeeling Limited. Dir. Wes Anderson. Searchlight Pictures. 2007. USA.

Bibliography

Horowitz, John. 2007. ‘Exclusive Featurette: The Slithery Star Of ‘Darjeeling Limited’ MTV Movies <https://www.mtv.com/news/87xis2/exclusive-the-slithery-star-of-darjeeling-limited>

Further Reading

Searchlight Pictures. 2007. Behind The Darjeeling Limited – Waris & the Cobra, online video recording, YouTube, 29 August <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yn8SGV-czts> [Accessed 24 October 2023]

Knight, C.R. 2014. ‘Who’s to Say?’: The Role of Pets in Wes Anderson’s Films. In: Kunze, P.C. (eds) The Films of Wes Anderson. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

More ZoomScope Zooms and Full Entries on the films of Wes Anderson

Hannington, Jessica. 2015. Animal Misunderstanding and Mystery in Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou. ZooScope. <https://zooscope.group.shef.ac.uk/the-life-aquatic-with-steve-zissou-dir-wes-anderson-touchstone-pictures-2004/>

Hennessy, Madeleine. 2018. On The Isle of Dogs. ZooScope. <https://zooscope.group.shef.ac.uk/isle-of-dogs/>

Lonsdale, Elliot. 2024. On The Rat Catcher. ZooScope. <https://zooscope.group.shef.ac.uk/the-rat-catcher-dir-wes-anderson-netflix-2023/>

Also by me: Bees in Rushmore. 2024. ZooScope. <https://zooscope.group.shef.ac.uk/rushmore-dir-wes-anderson-1998-buena-vista-pictures-usa/>