“I’m allergic to dying!“

-Pepe Rodriguez

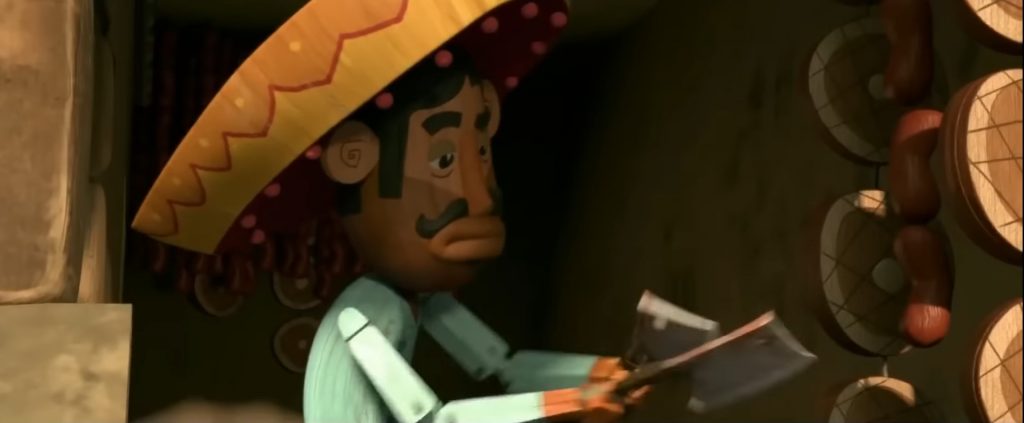

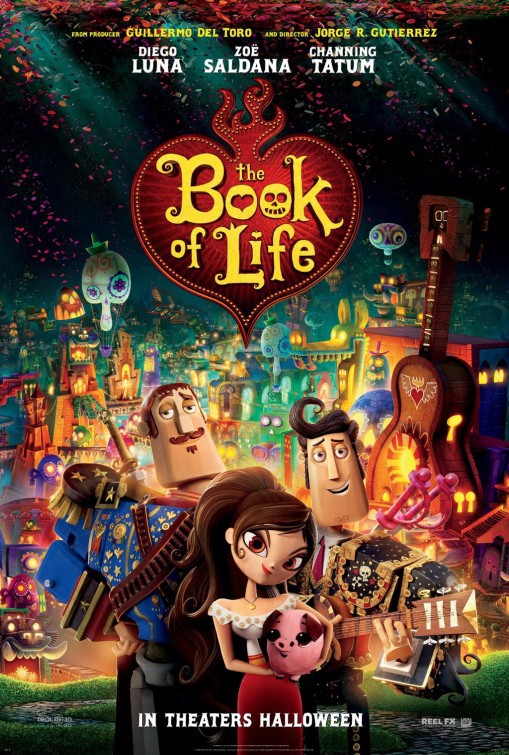

20th Century Fox’s, 2014, animated feature film, The Book of Life, follows two best friends, Manolo and Joaquin, who are in love with the same woman, Maria, our independent and fiercely empathetic heroine. The married gods, Xibalba and La Muerte, exchange bets on who will win her heart first, and it is their meddling with the lives of these humans that is the catalyst of the film. Joaquin, favoured by Xibalba, wishes to be a great warrior like his father and succeeds when given the Medal of Everlasting Life which while granting him immortality, blinds him with his own prestige. Manolo, favoured by La Muerte, is expected to become a bullfighter like his father and his ancestors before him, but secretly his heart yearns for music. He is tricked by Xibalba, who fears he will lose his bet, into entering the Land of the Dead, and must prove himself as pure of heart and face his fears of his father’s disappointment before he can return to his love and save his town from Chakal, a tribal leader desperate to be reunited with the Medal.

This animated, family film is an adventure-comedy set in Mexico. The film is a colourful celebration of Mexican culture which both exhibits the importance of love and acceptance, while also subverting this genre by, although gently, sparking a conversation on death. As critic, Susan Wloszczyna, states ““The Book of Life” personifies the philosophy that drives The Day of the Dead and encourages a healthy way to celebrate those who are gone.” [1] However, as with any good family film, the core moral story remains the same, good overcomes evil. It is the film’s demonstration of what is good and evil that interests me. There is a hierarchy between humans and animals from the beginning of the film. The bulls are a tool for our entertainment, and pigs are destined for our plates. But the film deliberately evokes our sympathy for the animals and encourages us to understand their suffering in a way that presents them as pure-hearted as our protagonist. Resultantly, the cruelty these animals face from humans is often mirrored in that which Manolo and Maria face. The characters that directly confront this hierarchy, challenging its authority, are those who achieve the most by the end of the film. Our heroes, Manolo and Maria, challenge their father’s desires in order to protect their respective animals, and ultimately find the love and acceptance of their family and each other. They “change the world”, [2] in the words of director Gutierrez. The Book of Life uses animals to represent purity being tainted by human cruelty. Consequently, their positions regularly mirror that of our pure-hearted heroes. Thus, by demonstrating empathy towards them, they are also on a journey of self-love, which will dismantle the hierarchies within their own lives. The animals are a tool to present that the true evil in the world is us.

This hierarchy is first made evident to the audience when Maria frees the pigs, including her future friend, Chuy, from slaughter. This scene begins with a close-up shot of Chuy gazing into the camera, adopting the viewpoint of Maria. This is then exchanged to be a close-up of Maria’s face, from the low angle of the pig. Gutierrez invites the audience through these shots to compare the two characters, both young, pure, and cute, gazing sweetly into one another’s eyes. At this moment, as the cameras frantically dart from the pair to the butcher in the window and the mural of cooking pigs on the wall, Maria has a realisation. Firstly, this pig, her equal in frame and position, is destined for a path it has not been allowed to choose for itself, as much as she is as well. While this pig’s fate is in the hands, or knives, of the butcher, her own is being determined by her father who already is displeased by her decisive nature. Secondly, she will allow it no longer. So, she turns to her friends in a striking pose of defiance, sword raised above her head as the sun rises signalling a new beginning, and declares, “we have to free the animals!”.

The response from her friends is equally as spirited, but not necessarily as supportive. Manolo replies “yeah!”, echoing her defiant pose, but Joaquin shouts “hold on, Maria, don’t!”, throwing his hand out to stop her. Ultimately, the hierarchy that Maria faces is a patriarchal one. She defies what is expected of her by this patriarchy to be a modest lady readying herself to marry well for the benefit of her town. At the young age of the characters within this scene, her falling for Joaquin is somewhat expected by the audience; for her knight in shining armour, or Medal, to come and sweep her off her feet. As E. Ann Kaplan explains “In Hollywood films… women are ultimately refused a voice, a discourse, and their desire is subjected to male desire. They live out silently frustrated lives, or, if they resist their placing, sacrifice their lives for their daring”. [3] However, The Book of Life defies this expectation. Maria is a warrior, of strong will, and fully capable of saving herself as much as she is capable of freeing the pigs. Therefore, when Joaquin denies this moment of freedom, moving to stop her, the scene foreshadows the fate of this love triangle. Joaquin wants her to be the weak maiden in need of saving, as he knows that he can provide the protection she needs and ultimately guarantees her hand. In turn, this is why he has no real connection to an animal within the film as he does not wish to dismantle a hierarchy that benefits him. He is an example of the bad in humans, ignorant of suffering outside their own needs. Conversely, Manolo, blindly follows Maria, copying her stance, and allowing her to lead the charge. He sees her for the strong, defiant woman she is and loves her nonetheless. It is this acknowledgement of the pig’s right to survive that presents him as deserving of her heart. They both see this creature, undeserving of its death, and wish to prevent the suffering it is set to endure. Therefore, it is this demonstration of empathy towards a creature in need of saving, which foreshadows the remainder of the film. That it is fighting for good against evil that will allow them to succeed.

Manolo also demonstrates this empathy in his refusal to kill the bulls. Both man and animal are forced to partake in the deathly dance within these scenes, despite their opposition. Bullfighting is a sport that is currently very controversial. In 2014, the release year of this film, the San Isidro bullfighting festival was suspended for the first time in 35 years after three matadors were injured. [4] According to PETA, as of 2013, attendance in Spanish stadiums was down by 40%. As of 2022, most of Mexico has banned bullfighting but is still allowed in the majority of Spain. [5] The sport has continued within Spain despite the cruelty because of a central theme of this film, tradition. In an intentional choice by Gutierrez, tradition unites the bull and Manolo, as he states in his ‘The Apology Song’ which he sings during his final bullfight, “we were bred to fight”. In this scene, as Manolo begins his song, the camera switches between close, facial shots of Manolo’s family, the bull and Xibalba. The is faced with the consequences of his actions to choose to sing rather than finish the giant, fiery bull standing before him. Then in an act reflective of the scene shared between Maria and Chuy, the camera remains focused on the matador and his final opponent as he sings his lament. However, the angles, from over-the-shoulder and wide, do not give the perspective of each other’s viewpoint but serve to highlight the size difference between the pair. Finally, the hierarchy between man and animal has flipped, at Manolo’s allowance, and it is apparent how much power the bull now holds. It seems aware of it too as it charges towards the hero, as we watch in an aerial shot, awaiting the death that is sure to come, unable to stop it from such a distance. But, the bull stops before the matador, lifting his foot to crush him instead, and again hesitates. Death is face to face with death, bone facing flame. But, in one of the film’s final acts of subversion, the film does not provide the action that an adventure film craves. Manolo offers the creature an end to the violence, which it accepts happily. Eventually, the bull douses the flames around the stadium and its own horns as the pair bow before one another. In this final act of purity, chooses life without reason to fight anymore and recognises the same within our hero. The camera remains low and the pair share most of their shots, having finally dismantled the hierarchy that has forced them to suffer for so long, tradition.

This clarity that the hierarchy between man and animal has finally ended is again established in the final fight. A tribe member holds the Medal of Everlasting life in his hands when Chuy enters the shot from over his shoulder. The camera closes in on the pig as he states in subtitled pig-language, “My comrades. Unleash the fury!”. The orange sky behind them has the same promise of death as the flames of the bull. Pigs close in on the tribe and wash them away while screaming in a wave of destruction, knocking the Medal from his hand. In this comedic moment, the cruelty of humans returns in the physical form of pigs. After years of slaughter at the hands of us humans, it is understandable that they would be filled with fury. Finally, the hierarchy between man and animals has been dismantled by our main heroes, and the consequences have been unleashed. Who better to unleash it upon that Chakal’s tribe, the epitome of evil? They show no remorse for their actions and are beyond saving like the Toro in the previous scene, which is why Chakal has to die. The film sets the president from the beginning that humans are the enemy rather than animals and this comes to a head in this comedic moment. The audience recognises for the final time that our own worst enemies are ourselves.

The animals in this film represent purity, neither figures of good nor bad. Animals act on instinct for survival alone, and it is human cruelty that drives them towards death and violence. This is presented in the film through a hierarchy between animals and man, which reflects the position of our pure-hearted heroes. Ultimately, this children’s film’s moral is a classic one; that good overcomes evil. The film uses animals to establish the true evil of this world not as death, but as us.

Bibliography:

The Book of Life, dir., Jorge R. Gutierrez (20th Century Fox, 2014).

[1] Wloszczyna, Susan., ‘The Book of Life’, RogerEbert.com, 2014 <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-book-of-life-2014> [accessed 7 January 2023].

[2] Carreón, Jorge., ‘How Director Jorge R. Guttierez Based ‘The Book of Life’ on His Own Life’, Desde Hollywood, 2014 <http://www.desdehollywood.com/director-jorge-r-guttierez-based-the-book-life-life/> [accessed 8 January 2023].

[3] Kaplan, E. Ann, Women & film (Routledge, 2013), pp.7-8.

[4] The Guardian, ‘Spain’s San Isidro bullfighting festival suspended after three matadors injured’, The Guardian, 2014

<Spain’s San Isidro bullfighting festival suspended after …https://www.theguardian.com › world › 2014 › may › s…> [accesssed 7 January 2023].

[5] PETA, ‘Bullfighting’, PETA, [n.d.] <https://www.peta.org/issues/animals-in-entertainment/cruel-sports/bullfighting/> [accessed 11 January 2023].

DeMello, Margo., Animals and society: An introduction to human-animal studies, (Columbia University Press, 2012) pp. 3-142.

Further Reading:

Coco, dir., Adrian Molina, and Lee Unkrich (Walt Disney Pictures, 2017)

Clara, ‘Ecocriticism Analysis: The Gluttony of Capitalism Results in Animal Cruelty as Depicted in Bong Joon-ho’s Okja‘, Medium, 2021 <https://chlaraphyll.medium.com/ecocriticism-analysis-the-gluttony-of-capitalism-results-in-animal-cruelty-as-depicted-in-bong-7fa376b3fef4>

Wells, Paul., The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture, (Rutgers University Press, 2009).

Wheeler, Duncan., ‘Bullfighting on Screen: A Hidden Chapter in the History of Film and Television’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 39.2 (2022, pp. 411-441.

Heise, Ursula K., ‘Plasmatic nature: Environmentalism and animated film’, Public Culture, 26.2 (2014), pp. 301-318.