Callum HowkinsMonday 16 January 2017

At the core of its various subplots, Seven Psychopaths revolves around a situation in which a trio of criminals steal dogs in order to claim the reward money offered by the owners. It becomes apparent that the animal is a vital part of this film, serving as a framing device for the tension in the narrative when gang boss Charlie Costello’s pet Shi Tzu falls victim to the scam. The film also questions whether a pet can truly be ‘owned’, examining the social relationship between humans and dogs and how the involvement of money affects the dynamic.

The kidnappers care for the animals and treat them as their own pets

One particularly significant scene demonstrates the operation in action, establishing the techniques used by the captors in order to take control of the dogs and manipulate the bond between human and animal to extort a financial reward from the owners. A montage splits the kidnap into four significant moments: an establishing shot of a woman walking through a park with her dog while being watched with binoculars; the owner looking frantically for her pet; the dog being placed in a cage and finally a quick cut to a shot of the owner placing a ‘missing’ poster on a street post. The rapid cuts between these shots is especially effective as it reveals the fragility of domesticity and human ownership by showing how the dogs are stolen and then resold as if they were any other personal object. As Sam Rockwell’s character gently comforts the dog it becomes clear that animal is calm and being provided with a safe environment. Importantly, the animals are not mistreated by the kidnappers in any way. The characters appear to genuinely care for the dogs and provide for them in a way which their true owners would. Because of this, Seven Psychopaths demonstrates a hypocrisy surrounding the use of animals as a form of product or commodity. By assigning a tangible value to a living being it becomes able to be traded freely between owners. The bond and emotional attachment which a human is inherently not something which can be bought, yet the film demonstrates how modern society treats animals as a form of ‘experience’ which can be valued as some sort of product to provide companionship and fulfilment.

The only way in which the con artists differ from the owners is that instead of using the animal as a personal ‘product’ they instead choose to sell to create profit. The ridiculousness of the situation is revealed when the dog’s free will is considered. It becomes apparent that an animal is incapable of being truly limited to the control of one owner, as the dogs have no understanding of the concept of ownership. No matter how much they were purchased for, the dog will never understand that the owner has ‘paid’ for it.

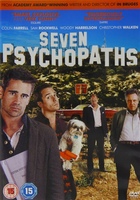

A still from the film demonstrating the exchange of money for a ‘lost’ dog

The premise of this scene demonstrates the relationship between humans and animals as clearly a one sided affair. The concept of financial reward in exchange for the safety of the animal is a problematic aspect inherent within human-animal relations as it treats a living being merely as a lost item which must be paid for by the human. The animal has no choice over its owner, even when they have parted ways there is a clear implication that the animal must return to its ‘rightful’ master. This twists the dynamic from one of mutual benefit into a situation which solely benefits the human and gives the dog agency whatsoever in the relationship. The preference of the dogs is unknown, yet the human is still able to exert a form of financial influence to reclaim the animal as if it were simply a missing possession. While the owners may not be committing a crime like the con artists, they are still guilty of assigning a fixed value to a living being and believing that they are therefore entitled to some form of control.