An Aesthetic Fantasy of Leonine Star-Vehicles: Whose Land is This?

Animal rights Activist Tippi Hedren and Director/husband Noel Marshall embarked on a several year journey to turn fantasy into reality by doing the seemingly impossible – shooting a film with hundreds of untamed lions, tigers and other African safari animals. With an unruly plot that matches the wild nature of the film, Hedren and Marshall’s passion project to humanise the ferocious cats boasts chaotic results.

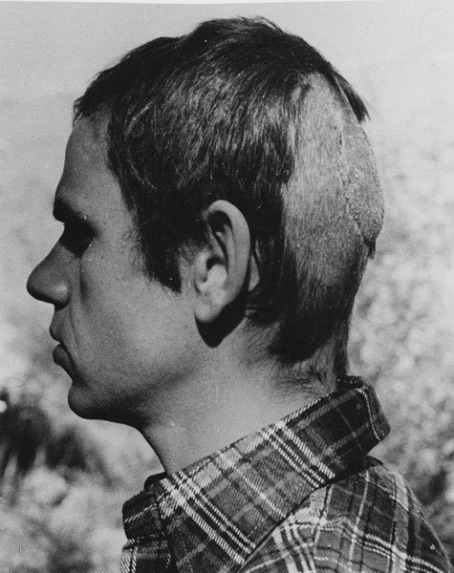

In a 1971 shoot with LIFE magazine, the Hedren-Marshall home was proven to be nothing short of eccentric, with a fully grown lion named Neil living amongst them:

The photoshoot depicts a utopian harmony between Neil the lion and the Hollywood household, serving as a stronghold to represent Hedren’s animal activist ideals, and portraying the films overall attempted message: that humans and animals can co-exist as one if we appreciate the inherent beauty of these majestic, endangered animals. This encapsulates the anthropomorphism the Hollywood couple tried to capture in Roar, with the lion posing as more than the average household kitty. Neil the lion is viewed as an equal, and not an animal, which can be attested to in the anthropomorphic shots of mutuality seen in the above images. This “Big Cat Fever”[1] seeps through in Marshall’s filmmaking and storytelling, as audiences witness the attempt (emphasis on attempt) to humanise these seemingly untameable creatures:

In this scene, Hank (played by director Noel Marshall) lets the lions and tigers out of the house with an endearing “come on lions”, and even goes onto name a few of them in order to single them out and get them to hurry up: “come on Diane, come on Patrick”. Naming the lions minimises their dangers to that of a household domesticated cat, animals which, on a frequent basis, become anthropomorphised in order to gain an enhanced connection between human and pet. Furthermore, naming them common Westernised human names affirms their characterisation and subverts their animalistic traits in this particular scene. Instead of partaking in nomenclature play by calling the lions names such as Cheeto or Noodle, Marshall puts the lions in the position of equal, therefore giving the wild cats a sense of humanisation, furthering their intended message of a harmonious co-existence. This is also relational to the LIFE photoshoot, as we see the lion, Neil, cohabiting with his human family as a named equal.

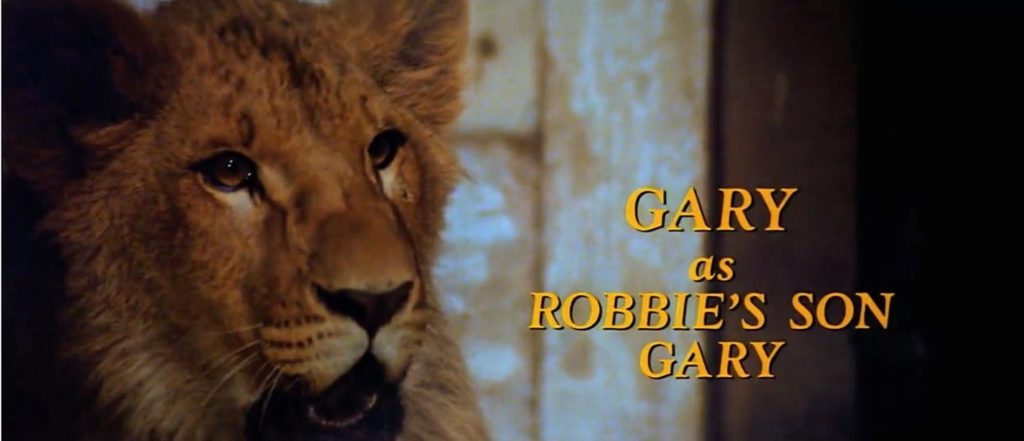

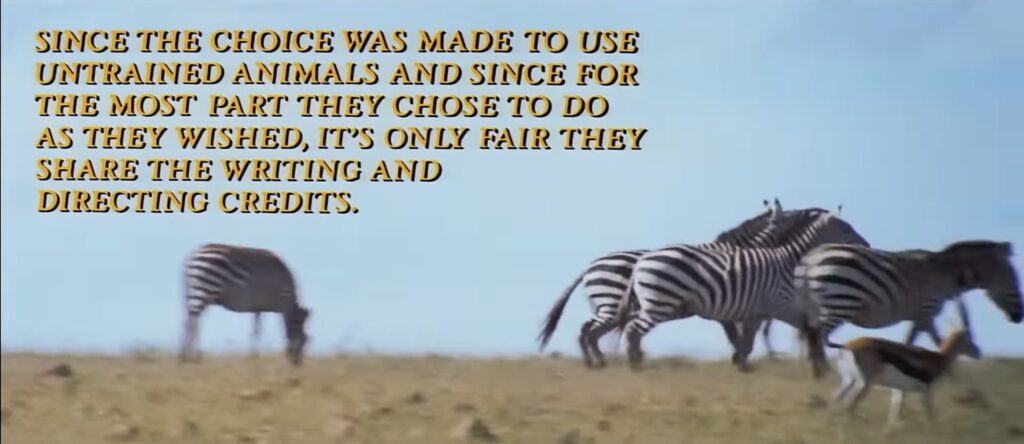

The scene then focalises on a lion cub, who is also named the western-centric name “Gary”. The audience are introduced to Gary through an endearing close up shot of the cub cooing and Hank addressing him with a warm “well, hello Gary”, and the cub in the corner replying in his adolescent roars. Here, the audience are presented with the spontaneity of the film, as Marshall pauses in the middle of a line as the cub interrupts him: H: “why didn’t you go with y-“ G: *roars* H: “Why didn’t you go with your friends”. Gary replies again. This ‘conversation’ humanises the cub and romanticises the alliance between humans and wild animals through these kinds of lighthearted interactions. The interruptions serve as a demonstration of the improvisation the actors had to do in order to capture the natural interactions between the actors and the animals. This furthers the narrative that the lions are considered equals in this film, as they co-create the plot by simply being free to do so. Because they are given the ability to alter the film depending on their actions, this even more so humanises the lions as they withhold a certain sense of power over the cast and crew.

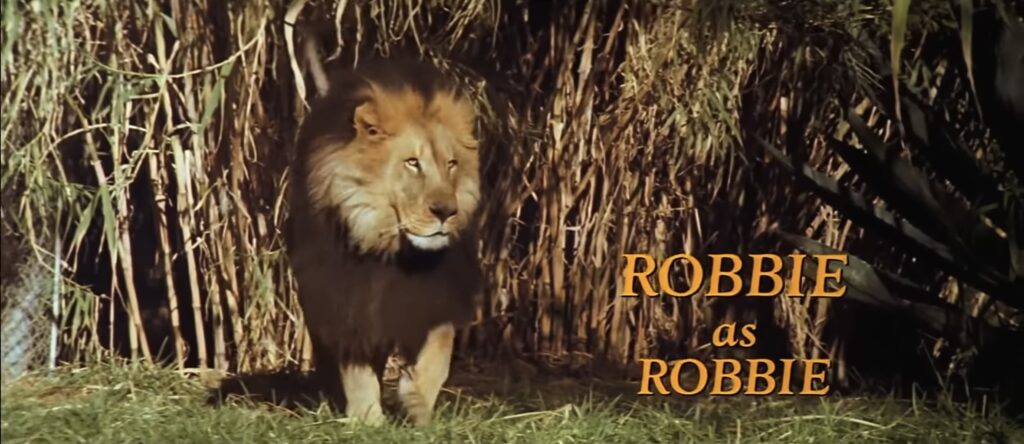

The egalitarian paradigm governing human-animal relations within the cinematic framework of the film is conspicuously established from the beginning. The opening sequence prominently features a title screen proclaiming a commitment to shared writing and directing credits, attributing agency to the animals who, as the narrative suggests, exercised their autonomy in the filmmaking process (figure 4). What Marshall does differently in this regard is that he tells his story of human-animal relationship and man’s place in nature. The subsequent scenes unfold with a distinct focus on the leonine cast, each lion granted individual recognition, both through visual representation and nomenclature. This deliberate emphasis serves to cultivate a connection between the audience and the animals, generating a personal acquaintance with the lions as sentient beings rather than cinematic tools deployed for narrative ends. The intentional decision to assign names and images to the lions from the outset establishes a narrative foundation that transcends the traditional anthropocentric perspective, prompting viewers to engage with these wild animals on a more intimate level. Whats even more intriguing is the stark contrast with the overt spotlight on the animal protagonists. Personalised visual moments are completely absent for any of their human co-stars in the opening credits. Instead, their names are integrated within a visual milieu featuring a multitude of wild animals freely traversing their natural habitat. This visual juxtaposition not only underscores the film’s commitment to egalitarianism in its portrayal of human-animal interactions but also subtly challenges conventional cinematic hierarchies by subverting the customary privileging of human subjects. In some essence, it could even be argued that Marshall and Hedren championed the animals so much that they viewed themselves as secondary in this film, with the lions as the star vehicle.

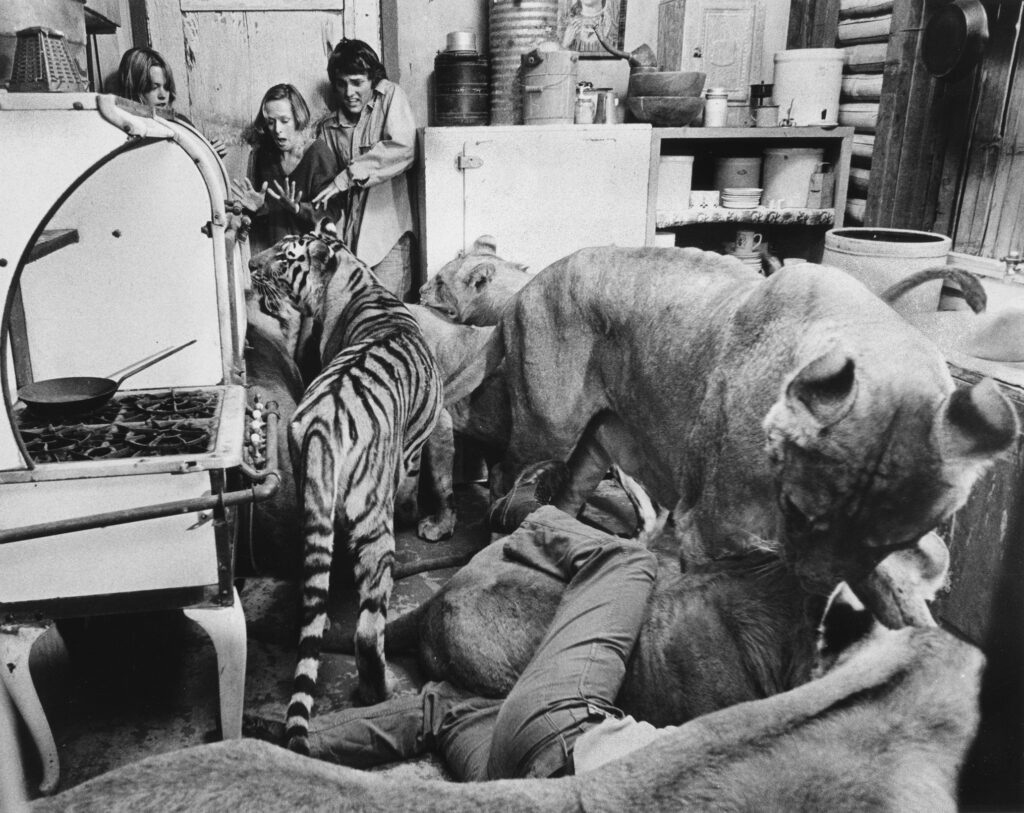

The power that the lions held over the film extended far beyond the big screen, with 70 people in total injured through the several years of shooting: a complete juxtaposition to Marshall and Hedren’s peaceful message, and an ironic contrast to the leisurely images we see in LIFE magazine (figure 5)

“Director of photography Jan de Bont was bitten in the head by a lion three and a half weeks into production. It took more than 120 stitches to sew his scalp back on.”[2]

These injuries were often the result of Marshall refusing to call cut on scenes in order to gain the most realistic encounters with these animals. Some of these unpredictable encounters -such as lions bringing Hank to the ground and smothering him -remain in the final cut of the film. (Figure 6)

This scene is played out comedically, with Mativo (Hanks more rational friend) adding playfully calm dialogue that creates a dissonant relationship between what viewers are watching versus what they are hearing, as he lacks any sense of urgency in the lines “Are you ok? You’re crazy!”. The dialogue here is so comedically mundane that it is clear that this is a common occurrence even though Hank is in a dangerous position which could potentially be life threatening. Mativo’s nonchalant reply to the situation that could have cost Hank his life is indicative of Roar as a cinematic experiment. Mativo’s humorously informal comments amidst the dangerous sights express the film’s larger story about how people can coexist with wild animals, minimising their dangers as the nonchalant scene plays out. Mativo’s mundanity in such an extraordinary context becomes symbolic of the daily struggles and unreal moments faced by actors during production. This narrative dissonance, however, is more than just comic relief but instead brings attention to the fact that this film is unique in the sense of its unpredictability and absurdity. Therefore, this calm answer from Mativo reinforces the ideology behind Roar; that its apparent chaos and inconsistencies are not random but rather intrinsic aspects of its artistic creation in order to capture the real. Through the dialogue, the everyday engagements with these cats are captured creating a communication which fashions their image from that of ferocious wild animals to those resembling harmless pets. This symbolic transaction underlines the subtle relationship ingrained through daily meetings, delinking the natural dangerousness of these creatures and a kind of domesticity they assume in those shared moments.

Multiple close-up shots of the lions and tigers are utilised throughout the film, most notably in the scene where the subplot antagonists of the film, the hunters, shoot three lions and tigers, leading the films leonine antagonist, Togar, to attack them.

These close ups demonstrated in figures 7 and 8 allow for an in depth look at the lions’ emotions and expressions. These emotions portrayed on screen give the animals a sense of characterisation and control that goes beyond their inherent wild nature, as they are given a platform as actors rather than as animals, such as the lionesses look of pure fear on her face and Togar’s emotion of menacing determination to get his revenge on the human antagonists. Such emotion is typically only comprehended as human, therefore elevating the sense of empathy between the audience and the animals on screen as the audience can identify parallels between themselves and the lions. The underscoring in this scene over Togar’s intentional and motivated visage only heightens his humanity as he is portrayed as a fallible character with villainous qualities and the capability to be complex. This characterisation is comparable to the film The Bear by Jean-Jacques Annaud (1988), a film which also utilised real life animals, in this case, bears, which convey sequences of emotion giving them anthropomorphic qualities. (Figure 9)

Contrastively, though, The Bear presents itself as a more naturalistic portrayal of animal survival in the wild, and Roar has a heightened sense of absurdity as the central motif of the film relies on the grandiosity of Hank’s unconventional lifestyle. Despite the similarities with the cinematic close-up’s of the borderline human expressions, Roar continues it’s dramatised portrayal of animals through Togar by making him a threat to the pack, and therefore making him a villainous outsider. The contrasting film does have moments of conflict, but the plot focalises on the struggles the Kodiak bear cub and the grizzly bear face. Without a central villain, the plot sits in a state of naturalism and a grounded sense of reality. While we do see animals behaving as animals in their environment in Roar, we see a version of these animals we would never encounter in their natural habitats in the plains of Africa as they are often crowded around each other in small spaces in order to capture Hank’s feline craze. Amongst these many lions is Togar and Robbie, who are highlighted as the main lions in the film, with Togar serving as an antagonistic plot device to imbue dramatic elements into the narrative and Robbie the leonine hero. Having a sense of hero and villain in the lion pack furthers their human qualities, as Marshall seeks to create a heightened sense of character in these wild animals, which furthers their position as actors.

Overall, Roar remains an outstanding experiment on screen that is not restricted by the usual distinctions between humans and animals. A daring effort by Tippi Hedren and Noel Marshall to make a film featuring wild lions and other safari animals led to more than just chaotic and unpredictable scenes but also resulted in a form of anthropomorphism. These lions are changed from being wild animals existing in their natural environments to having certain distinguishing traits such as personality, emotions, heroics and villainy dynamics and intimate close-ups. The filmmakers’ dream of coexistence between human beings and wild animals is made evident through the intentional contrast between the Hollywood household depicted in the LIFE magazine photo shoot and at times dangerous unpredictability of these animals during filming. The equal weight given to both humans and non-human participants in the opening credits undermines usual film hierarchies while reinforcing a vision of peaceful coexistence, leaving viewers to really question “Whose Land is This”?

[1] Jen Yamato, “Exclusive: Watch a Lion Maul Melanie Griffith in ‘Roar,’” The Daily Beast, 2017 <https://www.thedailybeast.com/exclusive-watch-a-lion-maul-melanie-griffith-in-roar>.

[2]Kevin Polowy, “Long before ‘Tiger King’ there was ‘Roar,’ the most dangerous movie ever made” Yahoo Entertainment, 2020, “ <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/roar-movie-lion-attacks-melanie-griffith-tippi-hedren-most-dangerous-movie-ever-made-194504001.html?>

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Roar (1981) Directed by Noel Marshall, Filmways Pictures, accessed via YouTube.

Secondary Sources:

Polowy, Kevin, “Long before ‘Tiger King’ there was ‘Roar,’ the most dangerous movie ever made” Yahoo Entertainment, 2020, “ <https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/roar-movie-lion-attacks-melanie-griffith-tippi-hedren-most-dangerous-movie-ever-made-194504001.html?>

Yamato, Jen, “Exclusive: Watch a Lion Maul Melanie Griffith in ‘Roar,’” The Daily Beast, 2017

<https://www.thedailybeast.com/exclusive-watch-a-lion-maul-melanie-griffith-in-roar>

Further Reading:

Donovan, Sean, “Animalistic Laughter: Camping Anthropomorphism in Roar” The Cine-Files, 2019

Tibbs, Ros, “Roar: The 1980s Movie That Saw 70 People Injured by Lions,” Far Out Magazine, 2022

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/roar-1980s-movie-70-people-injured-lions/

“SCVHistory.Com LW2795 | Film-Arts | ‘Roar’ (1981) News Photo, 1977: Tippi Hedren, Melanie

Griffith, Jerry & John Marshall, Tiger, Lions” https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/lw2795.htm