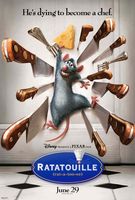

The final shot of Ratatouille, the image of a rat in the restaurant sign, symbolises the fantasy of the rat and human worlds crossing, and the idealisation of a rat chef being accepted by human society. However, this is ultimately impossible, as darker themes lurk beneath this image.

The sign features a silhouette of a rat wearing a chef’s hat and holding a spoon, staring across the Paris skyline. Ratatouille explores Remy’s journey of self-improvement and his quest to become like his idol, Gusteau, and this symbol encapsulates what he has achieved. The human and rat worlds have been transgressed by select individuals, shifting the mindset of the rats and some humans, but they are yet to fully assimilate. It is paradoxical that a rat, representing vermin and dirt, has become the symbol of fine dining and hygiene standards. Traditionally iconic animals are used as restaurant or pub signs, for example The Red Lion, it is amusing that a rat is used for a modern twist, showing the unconventional circumstances.

The sign also presents what he has not achieved; Remy has progressed beyond hiding in Linguini’s hat, the rat in the sign wearing one itself. Yet Remi is still hiding behind an object, that of a restaurant sign, maintaining secrecy and segregation between the rats and humans. This impossibility of the worlds crossing is furthered by the size of the spoon the rat holds in the sign. The spoon he holds is still too large for a rat. It is roughly tablespoon sized, indicating the sinister idea of the rat working for humans, not himself, which raises questions of ethics, possibly even indicating slavery. The sign echoes ideas of the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx, as Remi is a vehicle of the haute cuisine.[1] Remi is a reincarnation of the proletariat, and the humans as the bourgeoisie exploiting his labour for their own gain. His status is fixed, inferior to the humans. He has moved past the confines of Linguini’s hat, yet this has not liberated him entirely.

This symbol of Remy looking across Paris is a reoccurring symbol within Ratatouille, documenting his self-development. This image first appears as he emerges from the sewer and sits on a rooftop looking across Paris at the Eiffel Tower – at this point we acknowledge the contrast of what a minute animal he is in a huge city with no family or friends. This is the beginning of Remy’s journey, alien to his rat family yet to humans bearing the stereotypical identity of a sewer rat. The image progresses as his prosperity increases, repeated the first time he is in Linguine’s flat, and then in his ‘bedroom’ on the windowsill in Linguine’s new mansion. Remy’s lot in life increases, culminating in this sign. The rat in the sign is proudly looking out over Paris, as if he has conquered the city. However, this seems foolish and deluded. The proudness of this sign indicates their worlds have intertwined, yet he has only revealed himself to three humans. There is a romanticised grandeur about this sign, yet in the wider scope of human-animal relations, identity is concealed as the rats are still considered vermin and lesser. Segregation between the species is demonstrated by the rat restaurant being hidden above the human one.

Embed: scene in which Remi sees dead rats in pest control window – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4b1B30FeYOE

The mise en scene places the sign at the forefront of the shot and Paris further back, so the rat appears as large as the Eiffel Tower, no longer intimidated by the city. The backdrop of Paris, the stereotypical city of love, romanticises the idea of the two worlds crossing. This coming of age and growth of the protagonist is a typical theme in children’s films, so it is interesting to observe this in an animated animal. Conscious ambition is typically a human trope, thus Remy is anthropomorphised in his desire to advance in the human world, subverting our expectations of animals. Yet this sign is a fantasy, his species inhibits his potential, as prejudice and speciesism holds him back. His ambition is humanlike, but his ability to achieve this is severed by his breed.

[1] Karl Marx, Friedrich Engles, The Communist Manifesto, (London: Penguin Classics 2002).