After Verne, an anxious turtle, breaks through the boundary of the manicured hedge he enters a pristine garden on the periphery of a middle class suburbia. A far cry from the overgrown animal-populated wood, the suburban garden represents a natural environment controlled by humans, a place where that which is considered wild or ‘other’ is disciplined.

Divided by the hedge, an encapsulation of the boundary that humans wish to sustain between themselves and living animals, it is in the garden where the cruel human imagination and disregard for animals becomes overtly clear. This concept reworks ideas in Andrew Marvell’s pastoral poetry such as The Mower Against Gardens which explores the garden as a space for the brutal control of nature. Here in much of the same way as Over the Hedge, [1] human manipulation over the natural environment becomes so refined that the ‘flowers themselves were taught to paint’. [2] Marvell warns against meddling with natures order as its wilderness is absolute. However, this begs the question of how humans should interact with nature; Marvell warns away from ruining nature’s originality but offers no alternative. Some three hundred and fifty years on Over The Hedge tries to find a compromise between the harmonious existence of humans alongside animals but again struggles to do so.

On entering the garden, Verne’s horrified realisation of being an animal in a human environment is immediately captured close up by a low-level camera shot when he is confronted with towering animal ornaments. Perhaps most haunting is the concrete turtle almost identical to Verne. As the first ornament presented, it is significant as it epitomises the human perception of animals in the film; as something with little value beyond aesthetic. The symbolism of a concrete turtle struggling to support a heavy platform with a plant pot sitting comfortably on top instantly establishes a physical hierarchy of the human-animal relationship where humans objectify and manipulate animals as material and aesthetic commodities to establish themselves at the head of the hierarchy of life. It also demonstrates how natural imagery is being depressed by material culture and how urbanisation, due to human action and desire, is overtaking nature through the loss of habitat, misplacement of animals and clinical control of ‘wilderness’. Furthermore, as the ornament is monotonous grey concrete, it could highlight how humans perceive animals as insignificant. Its uninspiring greyness encourages the plant on top to flourish, reinforcing the manipulation of animals to fulfil a purpose to serve humans, in this case aesthetically. This in turn could hint towards wider moral issues relating to the exploitation of animals as a result of human control.

The depiction of human precedence over animals and their preference for inanimate animals as opposed to natural living beings is also reflected in the electrocution of an innocent dragonfly by a fatal blue light. The fact this image is in a pull focus draws attention to the electrocution light and the dragonfly’s murder but also considers the background image of Verne and his potential fate as the concrete ornament. Reiterating the dangerous fate of animals as inflicted by humans when animals infiltrate ‘human’ space,this suggests that human negotiation of and claim to space allows for the manipulation of the liveliness of animals. In keeping with film tradition, suburbia in Over The Hedge is presented as a disciplined environment which attempts to replace liveliness, embodied by the animals into a kind of cultural deadness which humanity promotes in order to uphold fickle pleasantries and notions of perfection. The animals in Over The Hedge attempt to reject these principles of a paradisiacal suburbia as other films such as American Beauty [3] have done in the past by uncovering its dystopic nature.

This persistent attitude towards the use of animals for human satisfaction is echoed in the film’s throwaway tagline ‘Get over it’. Blatantly a pun directly addressing the hedge, the tagline perhaps unintentionally resonates on a deeper level of sarcastic activism in order to confront its audience with the reality that morally, it is the duty of humans not to ‘Get over it’rather to get on with dissolving the hedge, and subsequently the perception that animals are at the mercy of human control.

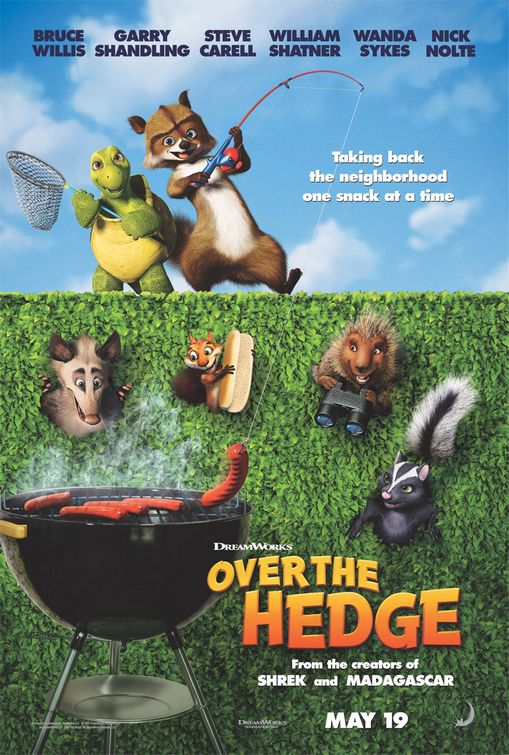

[1] Over the Hedge, dir. by Tim Johnson and Karey Kirkpatrick (DreamWorks: 2006).

[2] Andrew Marvell, ‘The Mower Against Gardens’, in Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/48333 [accessed 5 January 2017].

[3] American Beauty, dir. by Sam Mendes (DreamWorks, 1999).