Park Chan-wook’s 2003 film Oldboy is at its core a thriller, a revenge story of Oh Dae-su (played by Choi Min-sik) imprisoned in a room for 15 years without any knowledge of the reasons why, and who is then suddenly released back into the world and told by his captor to try to work out why he was held. Through this search for meaning behind his captivity, Oh blindly destroys anything in his path before discovering another horrific secret alongside the reason for his captivity – as a teen he unthinkingly exposed an incestual brother-sister relationship that led to the death of the sister, and has part of his punishment he has been tricked into a sexual relationship with his own daughter. Throughout this story, Park exposes some of the darkest parts of what constitutes humanity, sometimes diving deep into the worst parts of the human psyche but also often showing us the evil that lies worryingly close to our surface.

Park uses animals throughout the film primarily as a method of exposing the state of the characters that encounter them. Sometimes they act like a mirror, reflecting the harsh reality of the human characters in contrast to the softness of the animal, and at other times as a dark extension of the characters themselves. Park does not seem concerned primarily with the perception of the animals themselves in the film but rather what they can illuminate within the main characters of the story, either but contrast or but exaggeration and extension.

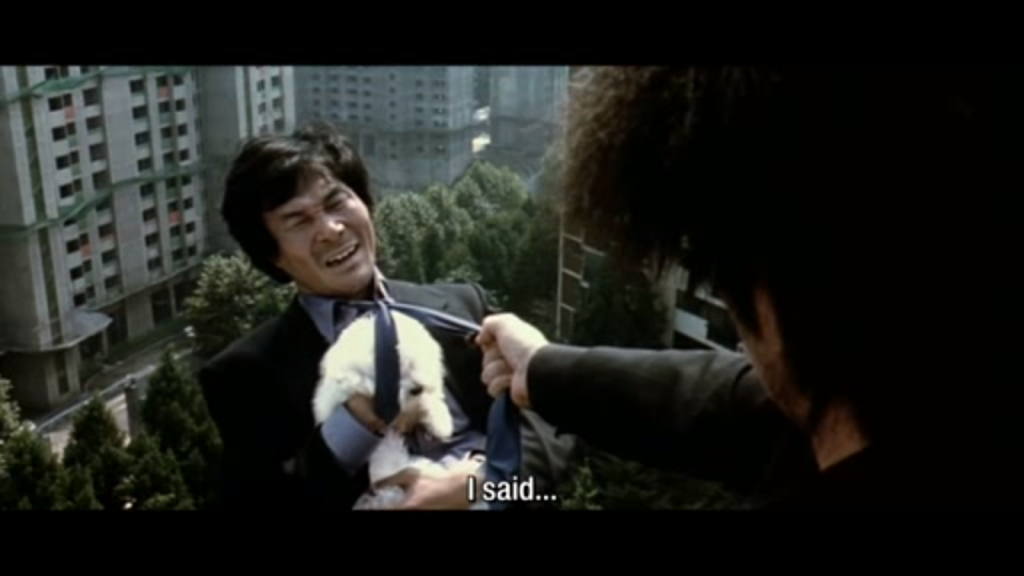

The opening shot of Oldboy shows us a man suspended over a street as he is held by his tie, a pure white dog clutched in his arms. Compared to the tone of the rest of the film that follows, this scene sits as a rather bizarrely humourous contrast to the dark violence that spreads throughout the events to follow. The man himself is dressed in a black suit, and when the camera turns to reveal Oh Dae-su holding him, Oh’s face and body are bathed in black – his black suit, long black hair, and shadowed face concealing him from the view of the camera – highlighting the pure white of the dog against the darkness. At this introductory point this scene serves as a hint of what is to come, seemingly using the strange imagery and contrast between the white of the dog and the darkness of the world around it for purely stylistic reasons, but when the film returns to this scene later the way in which we view the same imagery changes vastly.

The scenes with this dog bookend Oh’s capture and imprisonment and it is with our changed understanding of Oh and his reason for being on that roof and for holding that man’s tie that our perception of the dog and its contrast with the world around it is transformed. The seemingly purely stylistic highlighting of the white against black becomes a strongly placed metaphor, a highlighting of uncontaminated innocence against evil and darkness. As our understanding of the world of humanity increases, so does the distance between it and the world of animality – we combine our preconceptions of dogs as creatures of purity with the white fur of the animal and contrast it with the horror we have seen occur in the black world of Oh, the dog acting as a small beacon of ‘good’ in a pool of ‘evil’. When Oh opens the box and enters into the outside world it is first the sound of humanity that he hears in the form of cars driving past on the street and other industrial and mechanical noise. It is the bark of the dog, however, that is the first noise from a living being that Oh hears, before human speech of any kind, as if there is still a possibility that Oh could be welcomed back into the outside world and choose to embrace the innocence represented by the pure white dog.

Almost inevitably, this innocence is ignored completely as he grabs the (now revealed to be suicidal) man holding the dog, touching him and moving the man’s hand around his face as he desires the contact with another human body that he hasn’t felt for 15 years – his rejection of this innocence and embrace of the dark of humanity is then carried throughout the film as Oh swears violent revenge on the man who imprisoned him and causes death and destruction throughout this path. The discussions the film carries out later about humanity and its inevitable violence need the innocence of this dog in order to work, there must have been a possibility for man to reject the violent darkness in order for its true horror to be realised. It is Oh’s embrace and encapsulation of his human need for violence and revenge that is his downfall. In this sense the film follows a structure not unlike that of a Greek tragedy – in fact Park Chan-wook chose the name Oh Dae-su to remind viewers of Oedipus and its incestual parallels – as it is Oh’s original transgressions that lead to his punishment, as his rejection of this dog of innocence and choice for violent catharsis cause him to destroy himself.

The first line spoken by Oh after he gains his freedom is him repeating a phrase the suicidal man says to him: “Even though I’m no better than a beast… don’t I have the right to live?” This phrase directly compares human and animal (beast being a translation of the Korean word ‘jimseung/짐승’) and places human worth above that of an animal – for both these men, to exist at the level of beast is to be sub-human, but they still ask for the right to live. This suggests that there is a fairly clear cut structure in place where humans are seen as deserving life and animals are not, required those who are animal-like to make the case for their right to survive. That both men say this line shows us two separate things – firstly that they both consider themselves sub-human, but also that this understanding of the right to life is not one man’s perspective but rather a universal understanding of the right to life held by different beings. Despite this, neither man allows the dog to live as both are instead responsible for its violent death, Oh when he walks away from the suicidal man without listening to his story and the man for jumping with the dog. As if his rejection of innocence was not already great enough, humanity must remove it from the plane of existence with violence, the only tool at its disposal.

Animals do not always represent purity and innocence within Oldboy, however, as the use of ants throughout the film shows. The first appearance of the ants is during Oh’s imprisonment when he learns from the television that his wife has been murdered and he is believed to be the murderer. Seemingly in response to seeing this news, Oh begins to hallucinate ants crawling under his skin and eventually breaking through the surface and flooding his body. Where the white dog was set as a contrast to the darkness of humanity, these ants are for Oh an embodiment of that darkness. The preconceptions of ants that an audience would already hold are very different from that of a dog – ants themselves being associated with dirt rather than the cleanliness of an innocent dog. What starts as one ant under Oh’s skin quickly changes to a swarming mass, the line between each individual creature disappearing as they instead move as one body. This hallucination of the ants starting from inside the human body suggests that Park Chan-wook is showing us a human form that is not impenetrable, and from which evil can as easily escape as enter. In fact, whilst viewers of the film may read the ants in this way, as a physical embodiment of the metaphorical dirt that coats Oh Dae-su, the characters in the film are themselves aware of the power of ant imagery. Later in the film, when Mi-do (played by Kang Hye-jung) reads the diaries Oh wrote whilst imprisoned she comments that:

“If you’re alone, you see ants. People I have met who are very lonely have all hallucinated about ants. I tried once to work out why. Ants move around in groups, you know. So I suppose very lonely people keep thinking of ants. Although I have never done that.”

Mi-do reads the ant imagery hallucinated by Oh in a very different way, that the swarming over his body is a representation of his loneliness as he feels a kind of jealousy for the social structure that a swarm of ants has. Despite her claims to the contrary, Oldboy shows us that Mi-do has too experienced hallucinations of ants, but in a very different manner to those of Oh. We see that her hallucination was not of a swarm but rather of one ant of gigantic size sitting in the same way a human might in a train carriage with her. The fact that Mi-do not only understands that these ants have meaning but also that the meaning could be personal enough to keep her truth hidden away shows us that these characters are themselves very aware of the power of animal imagery, even if the previous scenes with the dog (and the famous live octopus eating scene) do not highlight this fact to us. Particularly important, however, is that Mi-do did not see a group of ants but a human sized individual, essentially undermining her own theory that hallucinations of ants are due to the swarms being a response to people’s loneliness – even within the film itself, she is refusing to come clean with regards to a true meaning behind the appearance of animals. For both Oh and Mi-do, however, the power of the ant is its ability to cut close to the truth behind its creator by breaking the boundary between animal and human, between the external and internal.

Overall, Oldboy depicts a world in which animals are seen as a reflection of the way humans treat them – either through a contrasting purity or an exaggeration of our own dark dirtiness. Park shows us the worst parts of humanity by showing us both the best and worst of animality and comparing us to it. Rather than laying down a strict relationship between humans and animals, he frequently plays with the boundaries between the two groups – including human-like animals and animals breaking out from within the human body. It is this perspective that allows us not just to see human or animal, but to read one through the body of the other and see deeper into ourselves in the process.

Bibliography

Park Chan-wook, dir., Oldboy (Show East/Tartan Films, 2003)

Choi-Hantke, Aryong and Hantke, Steffen, IKONEN Magazine, 2008 http://www.ikonenmagazin.de/interview/Park.htm [accessed 13 January 2019]

Cruz, Ronald Allan Lopez, ‘Mutations and Metamorphoses: Body Horror is Biological Horror’, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 40.4 (2012), 160-168 https://doi.org/10.1080/01956051.2012.654521

Pick, Anat, Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011)

Further Reading

Jung, Sun, Korean Masculinities and Transcultural Consumption: Yonsama, Rain, Oldboy, K-Pop Idols, (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010)

Jeon, Joseph Jonghyun; ‘Residual Selves: Trauma and Forgetting in Park Chan-Wook’s Oldboy’, positions, 17.3 (2009), 713–740 https://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-2009-021