Ken Loach (dir.) “Kes” 1969

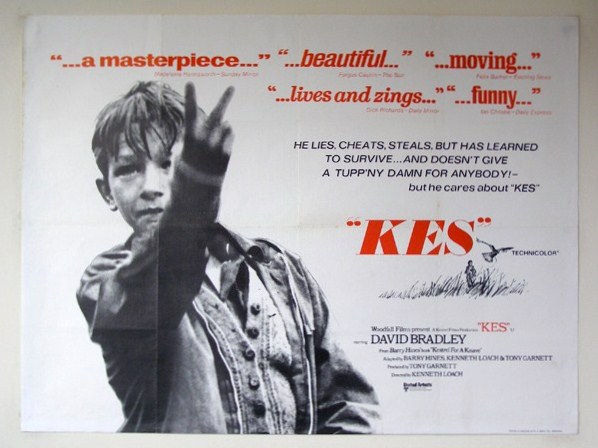

(Fig 1: Promotional Poster for the film)

Since the dawn of man Birds, or more precisely, the notion of flight, has fascinated humankind. Proud and mighty birds of prey have found their way onto flags and military insignia as symbols of strength, independence and freedom. As such, the idea of soaring through the air, free of constraints and sorrows, appeals the strongest to the downtrodden members of society.

Few film characters have ever been shown to be more downtrodden than Billy Casper, protagonists of Ken Lochs 1974 social drama, KES. The meek, scrawny and slightly thuggish 14-year-old, native to a small English coal-mining town, is as far apart from a traditional, strong protagonist as the genre allows; a poor, malnourished boy, subjected to constant bullying by his brother, teachers and peers. Billy’s luck seems to change, as his endeavor to raise an abandoned baby kestrel turns into a fulfilling and inspiring task, which allows Billy the dream of escaping the dreaded mines that inevitably lie in his future. [1]

Despite its grim setting, Kes never really seems to fit the genre of the classic drama. In stark contrast to the most popular drama films of recent years, the likes of “Shawshank Redemption”[2] and “Schindler’s List”[3], is not about individual strength and perseverance in the face of great danger. Kes offers no tyrannical warden, no brutal inmates and no sadistic Nazi officer. The films melancholic tone does not stem from some ubiquitous threat to Billy’s live, but rather from the apathy and feeling of meaninglessness that define him and most of the people around him. Ken Lochs slow building approach makes his life among northern England’s working class seem insufferably stagnant, with few people having more ambitions than working in the coal pits that define the region. The films primary antagonists, from his draconic Brother and bullying classmates to his non-caring mother and teachers, seem so much more mundane and commonplace, than the villains that accompany other films of the same genre. During its first half the film shows so little progress, or at least change in Billy’s profane life, that the viewer could be excused for thinking he’s watching a documentary rather than a drama. [4]

Aside from the films infamous football scene, Kes offers little comic relief. The gruff back-and-forth between Billy mother and teenage brother seems hurtful and cold, although it may have its comedic comments. Anyhow, Billy’s world stays grim and hopeless, until the eponymous “Kes”, a young Kestrel Billy steals form its nest, makes its entrance. The introduction of Kes sparks a change in Billy. Fascinated by the bird, Billy takes up falconry as a hobby. Although his brother and classmates are initially critical of his newfound passion and take up the chance to ridicule the outsider once again, Billy manages do deliver a passionate speech on Kes in class during which he earns his peers and teachers attention and respect.

(Fig 2: Billy being laughed at by his classmates)

A quick thought reveals the importance of the kestrel. Even though Loach pointed out that he “never thought of the Kestrel as a symbol”[5], Kes, with its eponymous Kestrel replaced by, for example, a stray dog or cat, would be a film about a wayward boy who seeks emotional refuge by adopting a pet. However, as Billy insists, Kes is no pet. His conversation with Farthing, his English Teacher, reveals the way he thinks about his companion. Kes’s elegance and beauty fascinates Billy and even Farthing, who resorts to quiet whispers in the presence of Kes. To him, the sight of the bird flying over their mutual training ground symbolizes a dream of independence and defiance. After all, birds of prey can be trained, but never tamed; they are indeed fierce and wild and bow to no man’s will, with their capability of flight being the ultimate symbol of freedom and escapism. As such, Kes is not only an emotional aid for Billy, but the inspiration to his newfound ambition and desire. [6]

(Fig 3: Billy inspects Kes)

During the first scenes, the film offers context to Billy’s dream of independence and freedom. We watch Billy and his Brother Jud lying in their shared bed until Jud hesitantly gets up to go to work in the local mines, but not before reminding his brother that “in another few weeks” he will be getting up with him. Billy insists that he will never work in the “pit”. Billy’s dislike of the mines is clarified again during his conversation with an employment officer who urges Billy the reconsider his stance on the mines, but Billy stays adamant. In these parts of the film, Kes reveals its social commentary, criticizing the lack of perspective within the working class. Working in the mines is implied to be dirty and hazardous and there are no true alternatives for someone like Billy.

(Fig 4: A painting depicting men leaving a UK colliery at the close of a shift.)

Within the film, the introduction of Kes brings some color to this grey world of mines and pubs. It serves as a strong juxtaposition of wasting ones live down in some dirty pit, or up, freely flying through the air without worries. The scenes of Billy training the bird are serene and shot in colorful meadows, providing a stark contrast to the natural, urban surroundings that a lot of the rest of the film takes place in.[7] Here we see Billy in peace, with no one there to disturb him, while most of his interactions with the adult world end with Billy being shouted at by a variety of teachers, employers, preachers and even his own family. The shots of Billy training the kestrel make him infinitely more likeable, showing that he is actually capable of being content and focused. Moreover his careful treatment of Kes reveals maturity far beyond his years in Billy.

The change in dynamic the introduction of Kes brings is also the key to the film’s hybrid nature. At first it seems content with surveying one of many wayward boys of the English working class. We are introduced to an inconspicuous boy and his uncaring environment, but Billy’s reticent nature makes it hard to feel genuine sympathy for him. Through the kestrel we get to see another side of Billy. A passionate boy fascinated by his newfound hobby and determined to master his craft. Like this, the film turns into a more personal drama, as Billy newfound hope inevitably sets him up for an even harder fall, as the film ends on another very grim note; with Billy’s brother Jud killing Kes.

Despite Loach’s denial, I see a strong symbolic link between Billy and Kes. The picture language of Billy training with the bird provides the unique contrast that makes Kes a touching film. The bird as a symbol of freedom is the antithesis to a life of working down in the claustrophobic coal mines, the fate that Billy so desperately tries to escape. It serves as a mean of juxtaposition, showing that there is still beauty and things worth preserving in Billy increasingly bland and cynical life.

Certainly, there is also a darker side to Billy’s relationship with his bird. When Billy demonstrates his training routine to him, Mr. Farthing remarks that the bird might rather be set free than to serve as Billy’s plaything. He then gasps, as Billy feeds Kes a dead sparrow, something that he finds disgusting. All in all, Kes comes off as more of a conception than an actual animal. It is never shown to do anything that is not expected of a Kestrel and all its traits, its implied ferocity and pride, are only projected onto it by Billy and Farthing.

This sets Kes apart from other films, which feature animals as main characters. Unlike for example Lassie or Babe[8], the kestrel has no explicit personality and the film and its does not rely on the kestrels actions to carry the plot. Another example of the kind of usage of animals in movies is Steven Spielbergs “Warhorse”[9], which features a horse as a central piece of the movie, but does not go out of its way to implement the horse as a hero or protagonist, even though the horse was given a lot of screen time.

References:

[1] Golding, Simon. Life after KES. Apex Publishing Ltd. 2014 (Chapter 4)

[2] Darabont, F. (dir.) The Shawshank Redemption. 1994

[3] Spielberg, S. (dir.) Schindler’s List. 1993

[4] Golding, Simon. Life after KES. Apex Publishing Ltd. 2014 (Chapter 4)

[5] Burt, Jonathan. Animals in Film. Reaktion Books Ltd. 2002, p. 191

[6] Ebert, R. in “RogerEbert.com

[7] Golding, Simon. Life after KES. Apex Publishing Ltd. 2014 (Chapter 4)

[8] Noonan, C. (dir.) Babe 1995

[9] Spielberg, S. (dir.) Warhorse. 2011

Literature:

Burt, Jonathan. Animals in Film. Reaktion Books Ltd. 2002

Golding, Simon. Life after KES. Apex Publishing Ltd. 2014

Films:

Darabont, F. (dir.) The Shawshank Redemption. 1994

Loach, K. (dir.) Kes. 1969

Noonan, C. (dir.) Babe 1995

Spielberg, S. (dir.) Schindler’s List. 1993

Spielberg, S. (dir.) Warhorse. 2011

Reviews:

Bradshaw, P. in “The Guardian“ : http://www.theguardian.com/film/2011/sep/08/kes-review

Ebert, R. in “RogerEbert.com” : http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/kes-1973