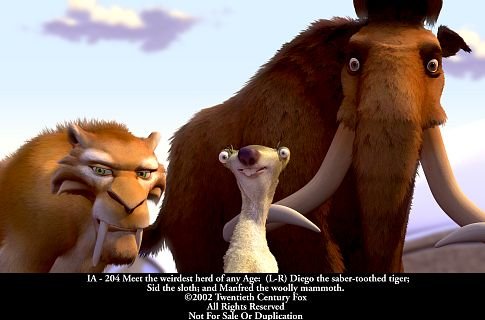

Set twenty thousand years ago, at a time when animals were migrating to warmer climates, Ice Age follows the story of three animals. Sid, a sloth, is left behind by his family, and meets Manny, a mammoth, who he decides to follow. They come across a human settlement which has been attacked by sabre-toothed cats. Manny and Sid discover a baby that has been separated from his parents and decide to search for his father to return him. Diego, a sabre-toothed cat, has been sent by his pack to find the baby; unable to take it from Manny and Sid he decides to travel with them, setting up a trap. However, on their way, the three animals reluctantly bond over the baby and become friends, braving both the deadly elements and the sabre-toothed pack together, they successfully return the baby. The only fictional animal in the film, Scrat, a sabre-toothed squirrel, has his own parallel Story Arc, attempting only to bury his beloved acorn, he manages to wreak havoc around himself.

Released in 2002, Ice Age was produced by Blue Sky Studios and distributed by 20th Century Fox. It is a Computer Generated Image (CGI) feature-length animated film, but considering animation is more a medium than a genre in itself, it also incorporates elements of other genres, including features of family film, adventure and comedy; particularly slapstick, but also satire and irony. Tudor states in terms of genre that, “Instead of defining the genre by attributes, it is defined by intention.”1 In this way, the intention of animated films is ordinarily primarily to make the audience laugh, but there is also usually a moral message to be learnt. A number of methods are used to achieve this, firstly, character animation which “attempts to present human traits in an expressive form that directs attention to the detail of gesture and the range of human emotions and experience.”2Ice Age does this through the range of high emotional states in the film, particularly, suspense, sadness and comedy, often seen in Sid’s depiction of hubris in his desperate attempts to “put sloths on the map”. Another element frequent in animation is anthropomorphism, “This can redefine or merely draw attention to characteristics which are taken for granted in live-action representations of human beings.”3 In addition, hyper-realism is also often used in animation “by making characters correspond as closely as possible to the ‘real world’ in their movement and context while allowing for fantasy elements in character and narrative.”4

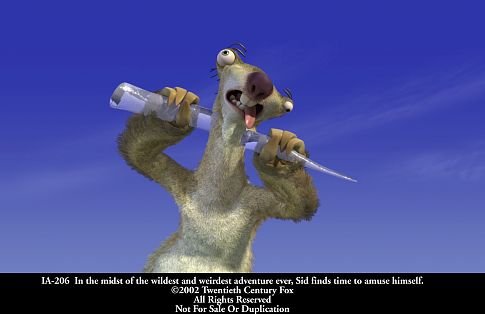

The anthropomorphic character animation in the film is most obvious in Wedge and Saldanha’s depiction of Sid, his enlarged eyes and nose add to the illusion of thought, emotion and personality in his character, features which are also used for Scrat. His stout frame and lisp further develop Sid into a loveable character. This bilateral lisp, which was developed when John Leguizamo, who voiced Sid, realised that sloth’s store food in their cheeks, altered Sid’s ‘s’ and ‘c’ sounds, making their pronunciation ‘spitty.’ This sigmatism is reminiscent of the development of speech in children; reminding us of Sid’s innocence, it has an endearing effect upon the audience. The film infers through these characteristics that the usually negative features of a speech impediment and being overweight are what make his character instantly loveable, suggesting in a wider sense that these are the characteristics, in both people and animals that make them likeable. In addition to this, Sid has a satirical sense of humour and playful nature, which can be seen below as he amuses himself pretending to be impaled.

This character animation can also be seen in the other characters, Manny’s enlarged eyes are particularly poignant in the scene where he is observing a wall painting of a family of mammoths. An over the shoulder shot switches to a close up of Manny’s eyes, evoking sympathy from the audience through his emotional reaction as his eyes widen in horror and his pupils dilate. Diego’s alert eyes are also important in the film; a strong green colour, they help to emphasise to the audience his evil motives, especially when Sid and Manny are asleep and his eyes open and glow in the dark, but after his sacrifice they remain partially closed and tranquil.

The three protagonists are depicted with a combination of anthropomorphism and animalisation. This anthropomorphism is aided by the character animation of the protagonists, but also the witty dialogue, particularly by Sid. The human and animal binaries are often blurred throughout the film, with the humans and animals often switching places. This is evident when the humans switch places from “hunters” to “hunted” as the pack of sabre-toothed cats plan to seek revenge. This contradicts the strong evolutionary history of humans as hunters, in addition to the hunting hypothesis, which proposes that human evolution was influenced, primarily, by the act of hunting, and that this activity differentiated humans from other hominins including orangutans, gorillas and chimpanzees. This subversion of the “hunter’s” to the “hunted” blurs the human and animal binaries in this way by suggesting a degeneration in the development of humans.

Moreover, the protagonists’ desire to “return Pinky(the baby) to his herd” allows for this animalistic view of the humans though the lexis “herd”. However, the animalisation of the pack works against this blurred binary through the pure violence and instinct which the pack show. Diego goes against this nature, and his pack, suggesting him to be an autonomous being, capable of emotion and thought. In this way, the three protagonists seem to be separate from the other animals in the film, more effectively anthropomorphised, they seem to be capable of higher reasoning and intelligence. This higher intelligence is particularly prevalent in the scene with the dodos as they chant “doom on you” and simulate Karate like movement, they seem to be of a lower intelligence than the protagonists, as a large group run off a cliff to their deaths, chasing after a melon. This slapstick scene clearly appeals to children, whilst there is still room for satire with the ironic line “there goes our last female”, appealing to an adult audience with a knowledge about the extinction of dodos. Witticisms such as this, and Sid’s quips about a “vegan diet” and “survival of the fittest”, combined with the slapstick comedy allow for the film to be placed securely in the “family film” genre due to its wide appeal. However, interestingly, the genre of the film seems to empty these appeals to the adult audience entirely of their meaning. Even though they recognise these witticisms, they are not encouraged to think about the implications of these ideas, suggesting these quips become an equivalent to ‘slapstick comedy’ for adults.

The animalisation of the three protagonists doesn’t take away the audience’s empathy with them, as even though Manny and Diego’s growling in the fight scene with the pack is animalistic, their motives allow us to see through this. These animal instincts are also mocked in the film in the scene where the baby is crying, Diego’s instinctual suggestions that “his nose is dry” and to “lick it” are swallowed by the ridiculous scene of Sid trying to change his nappy. This slapstick comedy overrides the animalisation in this scene, and allows the hilarity of three males, “bachelors”, as Sid refers to them, trying to take care of a baby to take centre stage. This acts as a spoof reminiscent of the 1980’s comedy film Three Men and a Baby, in which three bachelors adapt their lives in light of their pseudo-fatherhood, just like Sid, Manny and Diego.

Another feature common in animation is hyper-realism. In Ice Age, this is most obvious in Sid’s skiing scene, which can be seen below. This scene was researched by Blue Sky animators who went skiing in real life, they looked into the way the snow was tossed up by the skis, and the indentations they left behind in the snow and incorporated this into their animation. This extreme attention to detail exemplifies the way in which the hyper-realistic nature of the scene conflicts with its ridiculousness of Sid, a sloth, actually skiing. This feature is also evident in the scenes with Scrat, which emphasise the capabilities of CGI to portray hyper-realistic textures combined with comic timing. The visually stunning use of CGI software allows the mise-en-scéne to show the full scale of Scrat’s damage, making him more lovable in the process. Thus hyper-realism adds to the comedy of the film by making it slightly more lifelike and, in family film style, amusing for all ages.

The most important aspect of animal representation in Ice Age is the emotive response the protagonists gain from the audience. The tagline of the film “you look after each other in a herd” emphasises the bond between the characters as they are all united by the baby. This enables a peaceful interaction between the humans and animals, ensuring the message of bravery and unity reach the audience of this family film, in which the baby acts almost as a moral voice, particularly for Diego, but also the audience in general. This unity is assisted by the musical score of the film, composed by David Newman and performed by the Hollywood Studio Symphony, the use of a full band here allows for the build up and release of tension, whilst the recurring use of Rusted Root’s “Send Me on my Way”, frequently used in motion picture soundtracks, has a unifying effect, and demonstrates the adventure aspect to the film. This depiction of adventure and heroism is another important aspect of animal representation in the film. In the film poster below, the protagonists are coined “Sub-zero heroes”.

This suggests the protagonists to be altruistic beings, which prompts Bouse’s question, “can wild animals can be heroes?”5 He writes, “the protagonists are typically heroes whose morally unambiguous adventures offer escape rather than confrontation with difficult questions.”6 This can clearly be seen in Ice Age, where the difficult topics of hunting and the breaking of barriers between humans and animals are overridden with comic images and dialogue. However, in the case of this animated film, the protagonists can be seen as heroes in the delivery of the moral message of unity and teamwork in the film, which is one of the primary aims of a family film, in addition to its comedy and feel-good factor.

Whilst the film generally received positive reviews, Mitchell’s review in the New York Times criticizes the film’s failure in its attempts to adhere to the “Disney philosophy of required poignancy.”7 This poignancy is evident in the sense of sadness between the characters and their self-awareness that they will have to separate, before their final unity, which enables the delivery of the moral message in the film. This is something Mitchell refers to “cheap emotional gambits”8 where “this requisite melancholy makes us feel as if Ice Age has to apologise for being funny.”9 In contrast, film critic Roger Ebert stated “I would suggests the story sneaks up and eventually wins us over.”10 I think the film does eventually win over the audience through its use of loveable characters and that the ’emotional gambits’ that Mitchell refers to, only enhances their endearing personalities, particularly when individualist, Manfred, decides to remain with his ‘herd.’

However, this fantastical resolution at the end of the film, through both the unity of the three protagonists and the peaceful interaction between humans and animals, which parallels the reaffirmation of society and the human community, can also be problematic. Whilst the extinction and climate change themes add to the comedy of the plot, the real issue of global warming is easily skipped over. As “human politics are at the core of our responses to climate change”11, the education and power of the individual surrounding climate change should be very important. Ice Age seems to fall short of the “tremendous potential”12 that “children’s environmental literature has…for communicating messages about ecosocial injustice, community empowerment and strategies for ecosocial defence”13 that other children’s literature has also “not caught up to.” In Ice Age in particular, this ‘fantastical’ resolution for the protagonists raises concerns due to the unrealistic possibility of such a resolution in the bigger issue of climate change, which is largely caused by human influence. Therefore, the comic portrayal of the effects of climate change, particularly in the film’s sequel, Ice Age:The Meltdown, where the melting ice is transformed into a children’s water park, which can be seen below, is a concern because of the way in which this challenging issue is largely ignored.

Many animated films can be categorised in the adventure genre, with friendship and unity being a key theme in a large proportion of these. However, I feel that The Jungle Book, in particular, has many overlapping themes with Ice Age. In particular, the way the two male protagonists unite to look after a human child, and overcome the ‘evil’ of another animal. Similarly to Ice Age, the child must, despite the animals’ attachment, inevitably be returned to its fellow humans. It is clear from both films that, although the barriers between humans and animals at times become blurred, they must unavoidably be upheld.

1Barry Keith Grant, Film Genre Reader, (USA:University of Texas Press 1990) p4

2Jill Nelmes, An Introduction to Film Studies, (USA:Routledge 1996) p197

3Ibid

4Ibid

5Derek Bouse, Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), P128

6Ibid

7Elvis Mitchell, Ice Age (2002): Woolly Mammoths and Tigers and Sloths, Oh My!<http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9804EED61039F936A25750C0A9649C8B63>

8Ibid

9Ibid

10Robert Ebert, Ice Age (2002), <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ice-age-2002>

11 Serpil Oppermann.The Future Of Ecocriticism. (Cambridge Scholars Publishing:Newcastle, 2011). p47

12Ibid

13Ibid

Filmography

Ice Age (Dir. Chris Wedge, Carlos Saldanha ) 2002

Ice Age:The Meltdown (Dir. Carlos Saldanha) 2006

The Jungle Book (Dir. Wolfgang Reitherman) 1967

Three Men and a Baby (Dir. Leonard Nimoy) 1987

Bibliography

Bouse,Derek Wildlife Films (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000)

Ebert, Robert, Ice Age (2002), <http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ice-age-2002> [Accessed 20/01/2016]

Grant, Barry Keith, Film Genre Reader, (USA:University of Texas Press 1990)

Mitchell,Elvis, Ice Age (2002): Woolly Mammoths and Tigers and Sloths, Oh My!<http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9804EED61039F936A25750C0A9649C8B63> [Accessed 20/01/2016]

Nelmes, Jill, An Introduction to Film Studies, (USA:Routledge 1996)

Oppermann, Serpil.The Future Of Ecocriticism. (Cambridge Scholars Publishing:Newcastle, 2011)

Suggestions for further reading

Wells, Paul, Understanding Animation (Routledge, 1998)

Computer Graphics World, Volume: 25 Issue: 4 (April 2002)<http://www.cgw.com/Publications/CGW/2002/Volume-25-Issue-4-April-2002-/Ice-Pack.aspx> [Accessed 23/11/2015]

Film Trailer: