Part of the core ethics depicted within Saldanha’s Ferdinand (2017) is that the exploitation of animals, whether bullfighting or meat production, is unacceptable. However, the opening scene of this film depicts the bulls as having the agency to use their power to choose to fight and vie for the attention of the matador. By representing the bulls in this way, Saldanha unwittingly adds to the rhetoric that a bull is freely willing to participate in this sport without being forced through violence, therefore minimising the real-life harmful exploitation of these animals. This adds to the romanticised notion of an animal-human exchange of mutual understanding by showing that the bulls think of bullfighting as “a spiritual ‘test’ that ennobles both man and bull,”[1] much like a defender of the sport would. This portrayal of the bulls exists to further the plot, as it allows Ferdinand to become the hero who enlightens his fellow bulls to the harmful aspects of bullfighting, ultimately allowing him to save them.

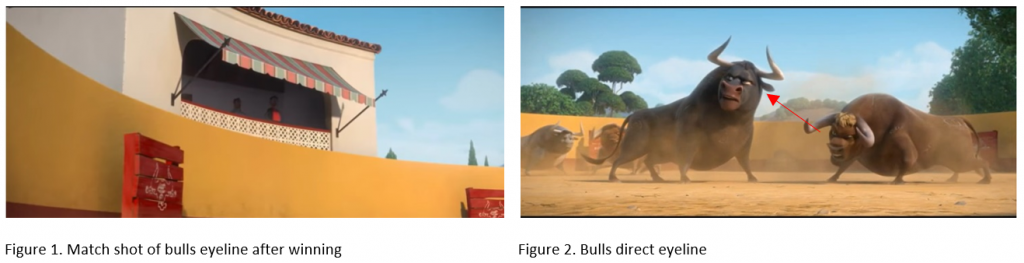

In this scene, the audience see the two remaining bulls fight for the matador’s attention. When the black bull wins, the camera tracks him as he stands victorious and a swish pan then occurs, following the bulls gaze and his point of view, landing on the matador. See figure 1 and 2.

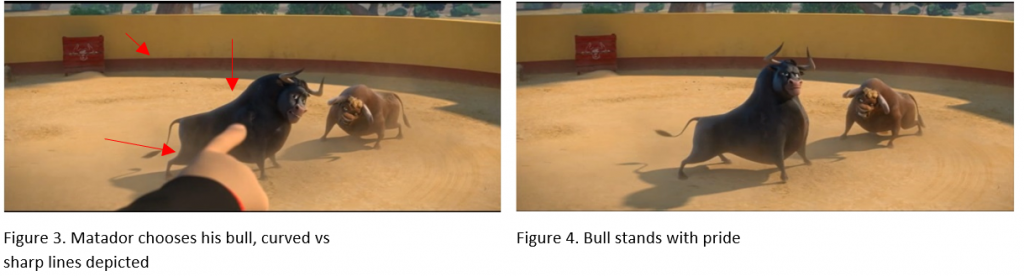

The use of POV and camera movement show the bull was anticipating the matador’s response and was performing for him. The implication here is that the human-animal interaction is one of understanding, and that the bull is actively wanting to be chosen. The scene cuts to matador’s POV, as he chooses the winner, causing the attention to be solely on the bull’s emotions as the shallow focus and depth of field blur the matador’s hand. The horizontal sharpness of the finger breaks the curvature of the mise-en-scene, displaying the earth-shattering importance of the matador’s decision to the bull. In response, the bull stands tall, proud to be chosen. See figures 3 and 4.

Depicting these animals as wanting validation for their fighting adds to the romanticised portrayal of human-animal interaction between bull and matador, implying that bulls understand that they will be harmed in the fighting, but that they are happy to partake for acclamation. The use of camera angles in this scene heightens the importance of this validation in a highly stylised way, with the movement of the camera and focus on the bull’s emotions allowing for no other interpretations. Although this scene allows the narrative to unfold by distinguishing Ferdinand as a passive and peaceful foil for these other aggressive bulls, this depiction of bulls as innately aggressive has been used to justify this cruel sport for years[2], and therefore this scene adds to the already misinformed societal representation of these animals.

This damaging portrayal is also present earlier in this scene. Here, the shot’s composition is formed from a low camera angle, and a horizontally split frame effectuated by the contrast of the saturated yellow enclosure with the blue sky. This framing causes the bulls to appear exaggeratedly strong in physique as they overpower the shot, rising above the constraints of the ring. see figure 5.

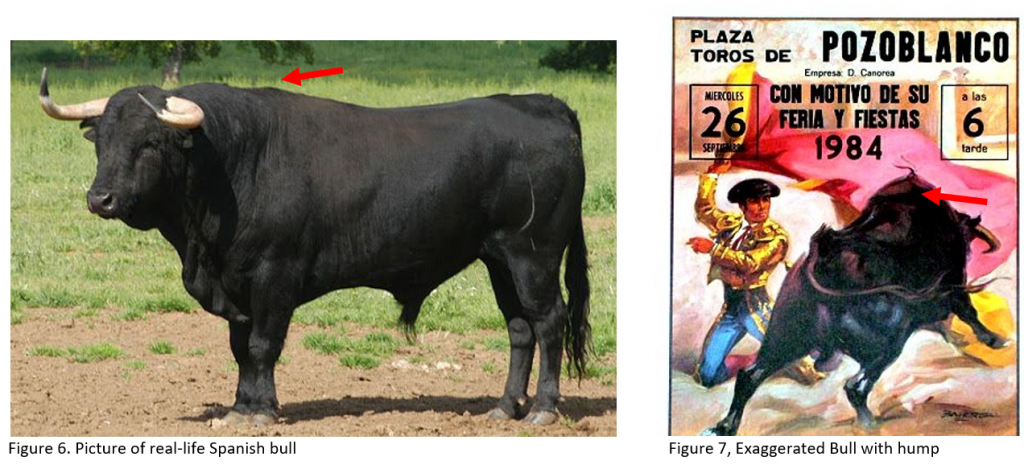

Their character design also adds to this portrayal of strength, as not only do their dark colours contrast the bright background, making them appear imposing, but they are also depicted with the oversized hump and muscular body that is romanticised by Spanish media to characterise them as a daunting opponent for the matador. See figures 6 and 7.

These bold character designs and use of bright colours within the mise-en-scene are necessary for the film’s success within the animated family film genre, as the characters of the bulls must be eye-catching and easily recognisable as Ferdinand’s antagonists for children[3]. However, by adding to the expected rhetoric surrounding the representation of bulls within media, Saldanha is complying with these conventions, rather than critiquing them.

In this sense, Ferdinand has its own version of the “Madagascar Problem”[4]. This means that Saldanha is struggling to reconcile the necessary anthropomorphising of these bulls for the success of the film within the genre, with the naturalistic portrayal of real-life animal traits and behaviours. As seen above, Saldanha attempts to overcome this by using the Bulls as avatars which work narratively to tackle bullfighting whilst also playing on our preconceived idea of bulls. These aspects, such as the character design and depiction of the bulls’ willingness to fight, work together to further the narrative, allowing for the film to condemn bullfighting in a way that a realistic portrayal of bull behaviour could not achieve within this genre. Despite the eventual condemnation of this sport, however, the mere idea that these bulls wanted to fight in the first place has its roots in real-life views used to keep this sport alive. Because of these real-world ramifications, this stereotypical portrayal is enough to derail the intended message, creating cracks in the ethical intentions, and causing the film to ultimately fail.

Bibliography

Duignan, Brian, 2018. The Romance and Reality of Bullfighting | Saving Earth | Encyclopedia Britannica. [online] Saving Earth | Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: <https://www.britannica.com/explore/savingearth/the-romance-and-reality-of-bullfighting-2> [Accessed 8 January 2022].

Humane Society International. 2008. Provoking Aggression in Bulls. [online] Available at: <https://www.hsi.org/news-media/aggression_in_bulls/> [Accessed 3 January 2022].

Naranjo-Bock, Catalina, 2011. Effective Use of Color and Graphics in Applications for Children, Part I: Toddlers and Preschoolers :: UXmatters. [online] Uxmatters.com. Available at: <https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2011/10/effective-use-of-color-and-graphics-in-applications-for-children-part-i-toddlers-and-preschoolers.php> [Accessed 8 January 2022].

Wells, Paul, 2009. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, pp.22-23.

[1] Brian Duignan, 2018. The Romance and Reality of Bullfighting | Saving Earth | Encyclopedia Britannica. [online] Saving Earth | Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: <https://www.britannica.com/explore/savingearth/the-romance-and-reality-of-bullfighting-2> [Accessed 8 January 2022].

[2] Humane Society International. 2008. Provoking Aggression in Bulls. [online] Available at: <https://www.hsi.org/news-media/aggression_in_bulls/> [Accessed 3 January 2022].

[3] Catalina Naranjo-Bock, 2011. Effective Use of Color and Graphics in Applications for Children, Part I: Toddlers and Preschoolers :: UXmatters. [online] Uxmatters.com. Available at: <https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2011/10/effective-use-of-color-and-graphics-in-applications-for-children-part-i-toddlers-and-preschoolers.php> [Accessed 8 January 2022].

[4] Paul Wells, 2009. The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, pp.22-23.