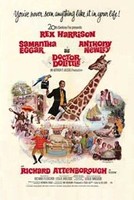

The genesis for Richard Fleischer’s 1967 film Doctor Dolittle came from Hugh Lofting’s successful chain of children’s books first published in 1920, and focuses on the character of a veterinarian named John Dolittle (Rex Harrison), who can talk to animals after being taught by his multilingual pet parrot Polynesia. The film is bursting at the seams with animal presences as the story follows Dolittle, the young boy Tommy Stubbins (William Dix) and the Irishman Matthew Mugg (Anthony Newley) as they join the local Circus showcasing a rare (sadly fictitious) two headed Llama, in order to earn enough money to set sail on a voyage in search of the ‘Great Pink Sea Snail’ (alas, again, fictitious). After setbacks from the local community and a jailbreak from the village asylum orchestrated by Dolittle’s animal friends, they set sail, joined by the adventure seeking lady, Emma Fairfax (Samantha Eggar). On their journey they are shipwrecked, they escape death from the natives of a floating island, and eventually meet the ‘Great Pink Sea Snail’ which allows all but the Doctor to sail home to England in the snail’s shell. Ultimately Dolittle learns the animals in England are on strike in order to attain his acquittal so he flies home to England on a ‘Giant Lunar Moth’. Cue credits and the happy ever after.

The screenplay by Leslie Bricusse amalgamates Lofting’s stories and encapsulates multiple film genres, including: adventure, comedy, fantasy and musical.

The Adventure Element: Was a grand attempt to trump the new American TV era by ‘seducing people away from the tiny box[1]’. Movie-goers attendance had plummeted from 90 million in 1946 to 41.6 million by 1961[2], hence Doctor Dolittle’s exotic location shooting in St. Lucia offered what television’s studio look couldn’t and competed with society’s ‘voguish leisure activity of travel[3]’.

The Fantasy Element: Aimed to enthral children who were the main target audience. Doctor Dolittle was to be a Disney film brought to life!

The Musical Element: Was the producers of 20th-Century Fox “riding a musical wave[4]” after previous successes such as The Sound of Music. They hoped that the sales of the films soundtrack would save them from crippling profit deficits.

The Comedy Element: Combined simple, visual comedy meant for the children, e.g. a horse wearing glasses, meanwhile, included more adult comedy such as jibes about Irishman Mugg’s drinking in order to please the parents of the young movie goers. The studio was trying to appeal to both demographics without either alienating the other.

So in true family film nature Doctor Dolittle advocates a chosen moral ethos. Here the party line is: ‘be kind to animals, they’re just like us. If we could communicate properly we’d all get along so well’. However, delve deeper into the film’s moral fabric and you will find things begin to unravel.

Interestingly, Doctor Dolittle abandons the nuclear family paradigm and instead has a new, jumbled collective of characters that mirrors a basic family construct. Emma appears like a mother/wife, Dolittle the father/ husband; Stubbins fulfils the son category, while Mugg appears like a sort of big brother. The chimp CheeChee is in constant tow of this ‘family’ and would presumably appear as a pet. But oddly, CheeChee appears more like a domestic slave member, a character with responsibility over chores who waits on the Doctor, rather than being cared for as a pet. It is this blurring of the distinction between pet and servant that I find problematic in the film.

Furthermore, in the scene where Polynesia teaches Dolittle that shaking the left leg means ‘good morning’ in animal language, the answer to Dolittle’s question “What was all the leg shaking business?”, is that a laughably obvious piece of clear wire can be seen twitching above Harrison’s right shoulder, yanking on the Parrot’s foot to make it behave in a desired manner.

https://www.lovefilm.com/film/?token=%3Fu%3D%252Fcatalog%252Ftitle%252F82545%26m%3DGET

This marionette like movement disturbs the nature of the seemingly innocent scene and undermines its facade of willing animal agency. The image here epitomises the film’s juxtaposition between liberation versus constraint. Humans are forcefully puppeteering animals, making them perform unnaturally for their own personal gain.

Unfortunately, Doctor Dolittle’s animal manipulation went on to yet more concerning levels off camera. For example, when producers wanted to film a squirrel attentively listening to Dolittle for a certain scene, naturally the squirrel wouldn’t sit still on the railing it was perched on for long enough, so trainers attempted to wrap wires around its paws and tack it to the rail. When this failed, the trainers filled a fountain pen with gin and fed it to the squirrel drop by drop. They managed to get ‘a few seconds of film showing the squirrel…nodding and swaying’ before it passed out[5]. This squirrel shot didn’t even make the final cut of the film.

The most saddening sequence I find in the film is the grandiose circus parade, which is overtured by the aptly titled song… ‘I’ve never seen anything like it’. During this montage the camera fades (in unintentional irony) between the animals circling inside the tent, and the ringleader Albert Blossom counting his profits. Here we see a plethora of excessively dressed up animals in a cruel procession, moving in uncomfortable and highly unnatural looking positions, which is in turn uncomfortable for any animal welfare concerned spectator to watch.

https://www.lovefilm.com/film/?token=%3Fu%3D%252Fcatalog%252Ftitle%252F82545%26m%3DGET

Disturbingly, a dog walking on its hind legs pushes another dog in a pram; other dogs are dragged, balancing on carts and jumping through hoops, a chimp is paraded in a carriage distastefully dressed like a Middle Eastern Prince. And finally, the piece de resistance is a bear looking very much like its struggling to walk continuously on its hind legs, its collar tactically concealed by a farcical ruff.

https://www.lovefilm.com/film/?token=%3Fu%3D%252Fcatalog%252Ftitle%252F82545%26m%3DGET

In more modern times the Circus has been red flagged by many as a potential danger zone for animal welfare. However, this age old family tradition of paying to see trained wild animals do ‘funny things’ and perform in unusual ways, sadly, still holds an irresistible attraction for some even today[6].

Unsurprisingly, the list of animal related complications is endless is terms of Doctor Dolittle’s film making. After producers ignored weather warnings for filming in Wiltshire’s rainy Castle Coombe, the fields the animals were kept in became like bogs. So much so many animals became sick and the rhinos even got pneumonia[7]! “Everywhere you walked there was either cow shit or mud[8]”, the set of Dolittle’s home even had to be built on a slant so that the sheer amount of animal faeces and urine could drain away[9]. Birds escaped their tethers and flew upwards, getting tangled in the soundstage netting and left to die. It was a constantly chaotic production.

St Lucia’s conditions were no better as swarms of tropical insects plagued filming[10] and very coincidentally, the St Lucian children were struck down by a persistent gastrointestinal illness spread by freshwater snails. This made filming with the prop of a colossal pink sea snail a tad awkward…villagers took it as an insult, removed it from the beach and sabotaged it with rocks[11]. Take that Hollywood capitalism.

https://www.lovefilm.com/film/?token=%3Fu%3D%252Fcatalog%252Ftitle%252F82545%26m%3DGET

In conclusion, Doctor Dolittle adopts the ethical tenet of Extensionism, which is to morally extend “consideration to animals based on their shared capacities and characteristics with human beings[12]”. However, for a film that suggests such human and animal equality, it actually manages to depict animals as entirely vulnerable and ultimately powerless to exploitation at the hand of humans.

The film’s ethical aim, which suggests that animals have feelings, is counteracted by its treatment and portrayal of animals both on and off the camera, and I believe this is due to Fox’s absolute desperation to regain profit and make the film a success after being faced with so many setbacks. Because of these setbacks, Doctor Dolittle takes its disregard for the truthful representation of animals to abusive lengths and evidently, mistreatment erupted off camera and spilled over into the film. Perhaps if Fox had not been in such an economic lull, this may not have happened?

Instances such as: mice being strapped to tail straightening contraptions, puppies swinging in coat pockets, chimps made to cook, seals dressed as babies in prams and fish dumped out of tanks from a height, in hind sight, probably were not animal friendly and would not be allowed today. Fox’s frantic, monetary greed and fraught desire to entertain audiences with this extravagant spectacle resulted in a film that simultaneously resists and problematizes animal discrimination.

Some immediate comparisons I thought of after watching Doctor Dolittle was Disney’s animated Dumbo and James Hill’s Born Free. The two films paradoxically reflect each other as Dumbo is an animated children’s film that offers the poignantly saddening perspective of animals living in Circus captivity, which is the opposite perspective to Doctor Dolittle! This unhappy animal viewpoint is particularly acute for me in a scene reminiscent of the grand parade in Doctor Dolittle, where Dumbo is being made to perform at a great height in the Circus, dressed as a baby (like many animals are in Doctor Dolittle), all for the benefit of the Circus’ profits and audience entertainment. In this Circus setting Doctor Dolittle offers ringside seats for the unpleasant animal spectacle, while Dumbo gazes outwards from inside the Circus ring, through frightened eyes towards the braying audience.

Born Free deals with the question of whether it is right to attempt to domesticate naturally wild animals, (this is a question Doctor Dolittle ignores) and for me, also inspires the question whether an animal friend on camera could potentially be more like a prisoner off camera? What I find interesting in Born Free is that to an extent it does advocate the idea that wild animals can happily find connections with humans. So perhaps some of the animals used in Doctor Dolittle could well have been happy and contented? One of the chimps used to play CheeChee (named Cheeta) had starred in many films previous to this role, and had a long, continuously prosperous life on film sets[13]. He even ended up with an autobiography! However, I believe Born Free reaches the appropriate conclusion that there are boundaries that need to be respected when it comes to usually undomesticated animals and humans, and these are boundaries that Doctor Dolittlecrosses, to inadvertently cruel effect[14].

Primary Sources

- Casper, Drew, Post War Hollywood 1946-1962, (UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2007)

- Harris, Mark, Scenes From a Revolution. The Birth of New Hollywood, (UK: Canongate Books, 2008)

- Pick, Anat, Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film, (USA: Columbia University Press, 2011)

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0061584/news?year=2008 (Accessed 8/05/2013, 18:02 pm)

Secondary Sources/ Suggested Reading List.

- Collins, A. Robert and Pearce, Howard D., ed., The Scope of the Fantastic-Culture, Biography, Themes, Children’s Literature. Selected Essays from the First International Conference on the Fantastic in Literature and Film, (USA: Greenwood Press, 1985)

- Wojcik-Andrews, Ian, Children’s Films. History, Ideology, Pedagogy, Theory, ed. by Jack Zipes, (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 2000)

- https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-407693/Un-bear-able-Chinas-cruel-animal-Olympics-reach-new-heights.html (Accessed 5/05/2013, 10:45 pm)

Filmography.

- Fleischer, Richard, Doctor Dolittle, 20th-Century Fox (USA 1967)

- Sharpsteen, Ben. (Supervising Director), Dumbo, Disney(USA 1941)

- Hill, James, Born Free, Columbia Pictures (USA 1966)

[1] Drew Casper, Post War Hollywood 1946-1962, (UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2007), p. 50.

[2] Ibid., p. 43.

[3] Ibid., p. 50.

[4] Mark Harris, Scenes From a Revolution. The Birth of New Hollywood, (UK: Canongate Books, 2008), p. 357.

[5] Ibid., p. 201.

[6] https://www.msunderestimated.com/2006/09/what-will-people-do-to-animals-next/ (Accessed 5/05/2013, 10:58 am)

[7] Mark Harris, Scenes From a Revolution. The Birth of a New Hollywood, p. 200.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., p. 241.

[11] Ibid., p. 243.

[12]Anat Pick, Creaturely Poetics: Animality and Vulnerability in Literature and Film, (USA: Columbia University Press, 2011), p. 2.

[13] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0061584/news?year=2008 (Accessed 8/05/2013, 18:02 pm)

[14] Suggested viewing: Werner Herzog’s 2005 film The Grizzly Man, for the examination of human/animal boundaries.