‘You’ve yet to learn about your greatest allies: the ants. Loyal, brave, and your partners on this job.’

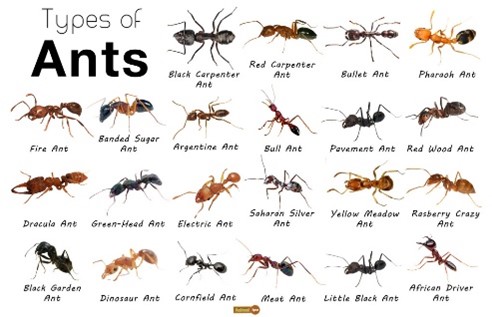

As you’ve undoubtedly predicted from the title, ants play a huge role in Marvel’s Ant-Man[1] (2015). Master burglar Scott Lang, recently released from prison, is determined to cease his criminal ways so he can become a proper dad to his daughter. But when money grows ever tighter, he decides he needs one last score – so, he steals the extraordinarily powerful Ant-Man suit from genius millionare Hank Pym. To Scott’s disbelief, he’s enlisted by Hank to help him stop the Yellowjacket, the dangerous creation of his scorned protégé, Darren Cross, who has honed his own shrinking technology by experimenting on lambs. Aside from gaining some cool new powers from the suit, Scott gains command over a gigantic colony of ants (fig. 1). These ants are described by Hank as ‘loyal, brave, and your partners on the job’; however, these ants are frequently put in harms way and as such: is it really ethical to commodify non-human animals like this?

It’d be easy to write off this movie as a conventional action-packed comic-book caper about a random man attaining superhuman powers. But it’s clear to see that the real heroes here are the ants – how far would Scott really have got without them? Obviously, real ants aren’t used in the movie: one of the major reasons for this being that it’d be virtually impossible to train ants to do all the sorts of things the Ant-Man ants do (fig. 2). But even though these specific ants are CGI, it’s still interesting to consider how they’re treated in the context of the film – these ants are employed as weapons, as architects, as rafts to sail upon, as spies, as a method of flight, amongst other things. Symbolically, ants represent ‘laudatory industry, diligence, humility and organisation’[2] (fig. 3), and these traits are absolutely seen throughout the movie. Although Hank refers to them as his ‘associates’, his way of making them do what he wants them to do is by using ‘electromagnetic waves to stimulate their olfactory nerve centre’, which sounds less like ‘speaking to them’ and more like mind control to me.

People often question the sentience of insects, seeing them as lesser beings that don’t feel pain or emotion as acutely as humans or mammals do (fig. 4). They’re considered to be like tiny mindless robots, with one reviewer of Ant-Man even writing that an ant ‘just crawled across my laptop screen, and […] I crushed its tiny body between my thumb and forefinger’[3], exhibiting the level of separation and desensitisation that people feel towards these creatures even when presented with a movie that portrays them in a fairly domesticated, puppy-like way. People will watch the movie and might care for a fleeting moment, but as soon as they walk away from their screens the prospect of caring very much about these little bugs could seem almost ludicrous to them.

The CGI ants are characterised in a way that’s evocative of pets rather than the less friendly way insects would usually be portrayed, which makes them far more enticing to an audience that probably either dislikes or is uninterested in ants (fig. 5). Director Peyton Reed said ‘I liked the idea of recontextualising the ant as sort of like a little puppy, like 101 Dalmatians’[4], which is particularly shown in the training scene in which Scott encounters the ‘Crazy Ants’. The scene is softly lit, with the orange ant drawing the eye as it’s the only true, bright point of colour onscreen at that moment. The ant squeaks happily as it leaps on Scott, just like a dog would – but when the rest of the ants do the same and pile on Scott in an excitable swarm, he becomes anxious and reverts back to his human size, exploding upwards from the earth and potentially crushing some ants under his feet as he does so. This demonstrates how even though the ants are painted as friendly, adorable ‘associates’, they are also seen contrastingly as being gross and scary.

‘He doesn’t have a name, he has a number, Scott, have you any idea how many ants there are?’

Scott Lang is shown to sincerely care about some of the ants in his service (after, of course, being a little bit frightened of some of them), even bestowing his own personal flying ant with the moniker Ant-thony (fig. 6), which lends this particular ant a degree of characterisation and individuality enabling the audience to grow attached to him just as Scott does. His death scene (fig. 7) is notable in the sense that insects do not usually get proper death scenes akin to those of humans or their close animal (usually mammal) companions. But Ant-thony is granted a highly emotive death scene reminiscent of Hedwig’s death in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1[5] – Cross’s bullet strikes Ant-thony, knocking Scott from his back. The extra-diegetic score here is delicate and poignant, and over it we hear the intra-diegetic sounds of Ant-thony’s anguished cry and Scott yelling his name as the flying ant plummets to his death. Ant-thony’s severed wing glides hauntingly through the space like a ghost before gently reaching the ground, and the shot cuts to Scott as he helplessly watches from the back of another flying ant. Scott is furious at the death of his friend, growling to Cross that ‘you’re gonna regret that’. In portraying Ant-thony’s death scene in such a manner, it’s clear to see both the blatant disregard for non-human life (Darren Cross) and the empathy for it (Scott Lang). On the topic of this, one journalist wrote that ‘Reed seems to have taken it as a personal challenge to see if it was possible to get an emotional reaction from the death of an ant, something most people step on every day without even noticing’[6], exemplifying, again, just how inconsequential the lives of insects really are to a lot of humans, and how opting to have a death scene for an ant comes across as unusual. But since the protagonist of the movie is deeply saddened by the death of his noble steed, it’s clear that the filmmakers want the audience to take a leaf out of Scott’s book and start being more empathetic to insects, too.

Figure 8 – a yellow jacket wasp.

Figure 9 – Darren Cross’s Yellowjacket suit.

The name of Darren Cross’s ‘Yellowjacket’ is striking as it refers to another type of insect (figs. 8 and 9): ‘the yellow jacket is a very aggressive wasp […] yellow jackets will aggressively attack en masse if they feel their nest is being threatened’[7]. Though we don’t physically see a yellow jacket wasp here, the inclusion of his suit being named as such makes the ants appear to be the ‘good’ type of insect and the yellow jackets the ‘evil’ type, when in reality, they both rely on instinct rather than a true level of morality. Moreover, near the end of the film, Cross, clad in his Yellowjacket armour, gets hurled into a bug zapper (fig. 10). Cross is a man who disregards any life other than his own – neither human nor non-human lives mean very much to him – and for him to be electrocuted by something humans put outside to eradicate pests is darkly ironic. He dons the visage of an insect and is thus treated as such.

‘I thought we were using mice?’ ‘What’s the difference?’

Figure 11 – a lamb being experimented on by Cross’s team.

Figure 12 – Dolly the sheep, who was genetically engineered by humans.

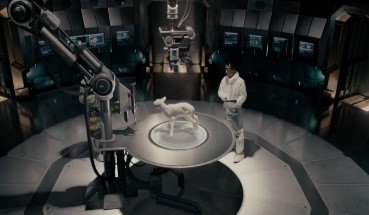

Humans are conditioned to be sympathetic towards some animals more than others; often the sweet and lovable animals garner far more compassion than those that are less cute. Darren Cross perfects his Yellowjacket shrinking technology on animals – more specifically, on lambs, which is seen as needlessly cruel (figs. 11 and 12). Hope Van Dyne, aghast when a small bleating lamb is lead into the laboratory, questions why they aren’t using mice. This raises an issue: why are some lives prized higher than others? It’s easier for people to be concerned about something if it’s cute and cuddly: ‘aesthetic and commercial standards have become the primary determinants of which species in the natural world deserve conservation’[8]. Lambs connote youthfulness and innocence, and therefore it’s seen as far crueler for them to be experimented upon than mice, as rodents often connote filthiness and disease. The mise-en-scene in this scene forges an atmosphere of cold, clinical horror revealing how truly nightmarish it can be when humanity decides to play God. A mechanical claw dangles insidiously above the lamb as Darren Cross watches intently, generating religious allusions as it places him above all else: a man who can experiment upon and murder any life he considers inferior to his own (fig. 13). The ominous score builds as the camera zooms into a harrowing close-up of the lamb’s face (fig. 14) before it is promptly killed by Cross’s faulty technology. Hope and the scientist are horrified by this senseless death, but Cross merely cares about the fact that this experiment was unsuccessful. This encapsulates the disconnect that many humans feel towards animal suffering and death unless the animal in question fits a narrative or is appealing to the eye.

Figure 13 – Darren Cross as a cold, callous god, manipulating and killing to achieve his ends.

Figure 14 – the little lamb shortly before its horrible death.

Ant-Man emphasises humanity’s commodification of non-human animals for its own gain (fig. 15), exemplifying the disconnect humans feel toward animals suffering. Insects, which are oftentimes seen as unimportant pests, are presented here as heroes, as friends, as worthy of their own significant and devastating death scenes alike to that of a human or close mammal companion. This film truly generates empathy for insects in the hearts of the audience. There are shades of grey in this portrayal, however, such as how Hank Pym refers to the ants as his loyal associates and yet commands them through their olfactory nerve centre. There is a rift very apparent between the way humans feel as though they perceive non-human animals and how they honestly do see them. We think we care, but not enough.

A mirror is held up to human-animal relations here – the CGI, puppy-like ants are the real heroes of the film, and yet are largely unnamed and fundamentally mind-controlled by Hank Pym. But through the cold, clinical ambiance of the laboratory in which the lamb was experimented upon, and the slow-motion, haunting death scene bestowed to Ant-thony, Reed constructs an environment in which it’s celebrated to care about animals. It poses the questions as to why some animals are regarded with more empathy than others, and why the CGI ants must be morphed into a more palatable version to be liked by audiences.

Ant-Man is a surprising Marvel movie that illustrates, right there in its title, just how import-ant those little insects truly are.

FILMOGRAPHY

[1] Ant-Man, dir. by Peyton Reed (Marvel Studios, 2015)

ITV, I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! (London Weekend Television and ITV Studios, 2002-)

Smith, Simon J., and Hickner, Steve, Bee Movie (DreamWorks Animation and Paramount Pictures, 2007)

[5] Yates, David, dir., Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2010)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[4] Hughes, Mark, ‘Interview with ‘Ant-Man’ Direction Peyton Reed’, Forbes, 2015 <https://www.forbes.com/sites/markhughes/2015/07/02/interview-with-ant-man-director-peyton-reed/?sh=76372d2742bc> [accessed 8th January 2022]

[6] Libbey, Dirk, ‘The One Ant-Man Question Concerned Fans Keep Asking the Director’, Cinemablend, 2015 <https://www.cinemablend.com/new/One-Ant-Man-Question-Concerned-Fans-Keep-Asking-Director-94167.html> [accessed 12th January 2022]

[8] Postmedia News, ‘Too Cute to Die? Experts Say We’re Too Selective About Species We Choose to Protect’, National Post, 2012 <https://nationalpost.com/news/too-cute-to-die-experts-say-were-too-selective-about-species-we-choose-to-protect> [accessed 7th January 2022]

[7] Sciencing, ‘Types of Wasps that are Very Aggressive’, Sciencing <https://sciencing.com/types-wasps-very-aggressive-8587648.html> [accessed 6th January 2022]

[3] Scott, A. O., ‘Review: ‘Ant-Man’, With Paul Rudd, Adds to a Superhero Infestation’, The New York Times, 2015 <https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/17/movies/review-ant-man-with-paul-rudd-adds-to-a-superhero-infestation.html> [accessed 12th January 2022]

[2] Werness, Hope B., The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism (New York: The Continuum International, 2003)

FURTHER READING

Adamo, Shelley Anne, ‘Do Insects Feel Pain? A Question at the Intersection of Animal Behaviour, Philosophy and Robotics’ Animal Behaviour, 11.1 (2016),75-79 <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003347216300513> [accessed 3rd January 2022]

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2002)

Lambert, Helen, Elwen, Angie, and D’Cruze, Neil, ‘Wouldn’t Hurt a Fly? A Review of Insect Cognition and Sentience in Relation to their Use as Food and Feed’ Science Direct, 243.1 (2021), <https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105432>

Ripley’s Believe it or Not, ‘This Three-Continent Ant Mega-Colony Will Conquer Earth Soon’, Ripley’s, 2019 < https://www.ripleys.com/weird-news/ant-mega-colony/>

Sleigh, Charlotte, Six Legs Better: A Cultural History of Myrmecology (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2007)