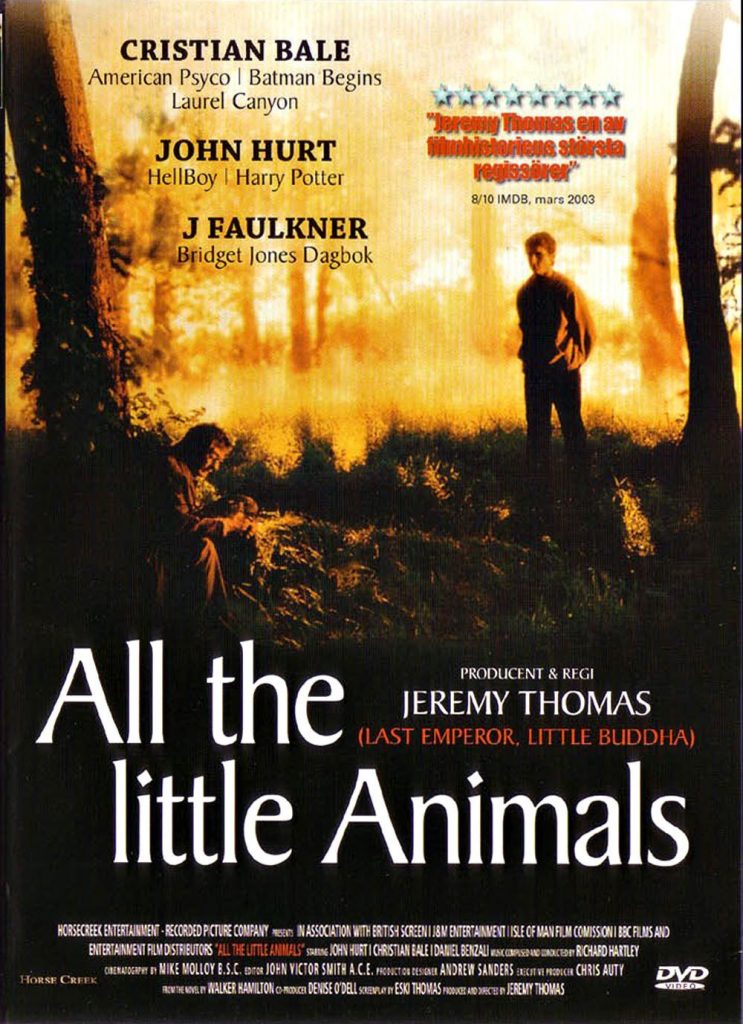

Bobby Platt is twenty-four with learning difficulties due to a car accident from his childhood which he refers to as “the most important thing about me”. Bobby’s stepfather, “The Fat” is the archetypal bully: aggressive and unsympathetic even at the death of Bobby’s mother. After her funeral The Fat instructs Bobby to sign over the family shop to him, but Bobby refuses. After The Fat kills Bobby’s mouse, Bobby flees to Cornwall where he meets the eccentric and loveable Mr Summers. When Mr Summers sees how passionate Bobby is about animals, he agrees to let Bobby join him in “The Work” -protecting animals from humans and burying those who have been killed on the road. One significant episode is when Bobby sabotages a lepidopterist’s work by smashing the light box used to lure in unsuspecting moths. In London they ask The Fat to allow Bobby his freedom in return for the family business. The Fat violently assaults Mr Summers and forces Bobby to direct him to their house. Mr Summers dies. Bobby wounds The Fat who chases Bobby in his car to a dock. Bobby dodges the Rolls Royce and it falls down a shaft, indicating The Fat’s imminent death.

Features of Melodrama

Melodrama as a Romantic, Nineteenth Century genre draws on the emotions of the audience. Coming from Greek, ‘melos’, meaning ‘music’ and ‘drama’, meaning ‘play’, the genre uses music to sensationalise the drama on stage/screen. [1] The film genre maintains many of those Nineteenth Century characteristics, such as the use of emotive music, simplified moral positions of good and evil, archetypal characters, such as the depraved step-parent and extravagant theatricality in gesture and plot. Melodrama involves ‘the acting out of moral statements’ as described in the British Film Institute’s Melodrama: Stage, Picture, Screen. [2]

Animal Presences

Jeremy Thomas depicts the world as a melodramatic place of opposites and absolutes, impressing upon his viewers the innocence of animals and the evil of harming them. From this a ‘good versus evil’ dichotomy is derived, with Mr Summers as a fairytale hero protecting Bobby and the animals against the villainous The Fat. All The Little Animals has a typically melodramatic plot structure, as the victimised protagonist runs away and is given a seemingly idyllic situation, which is then jeopardised so that he must fight to secure his freedom.

A balance is presented between animals and humans, also between nature and manmade technology. This can be seen in the symbolism of the Taijitu sign used in the trailer. The Taijitu in traditional Chinese religion illustrates opposites working in harmony.

The main action of the film in which Bobby is aged twenty-four is parenthesised by a scene from the present tense in which Bobby sits, long-haired with a dog on a hill in the countryside. The presence of the dog and the shot of the surrounding landscape portray Bobby’s comfort in nature and his love of animals. Folk music accompanies the rural visual setting, emphasising the pastoral atmosphere. This present narrative that frames the film assures the viewer that although they watch the protagonist being faced with perilous danger, he will be fine in the end. This enhances the fairytale-style plot, because eventually all will be resolved. Part of what makes this framing scene so assuring is the natural setting. Thomas depicts a peaceful present as being at one with nature and animals, one in which the balance between animals and humans is somewhat restored.

Bobby’s interactions with his mouse, Peter illustrate his admiration for animals and his escapism through talking to Peter, as he asks “Are you magic?” It is clear that Bobby, mentally abused by his step-father finds comfort in his relationship with Peter, as he treats him like a friend rather than a pet. Bobby seems to believe in Peter’s intelligence and personifies him by speaking to him. The Fat, aware of Bobby’s love for animals kills Peter out of malice. The scene shows The Fat throw the plastic bag containing Peter’s body at Bobby. The camera follows the mouse through the air in slow motion. This technique depicts Bobby’s shocking view in seeing his dead mouse and has the melodramatic effect of intensifying the viewer’s emotional reaction to his death.

The man who takes Bobby on the final part of his journey to Cornwall causes anaccident in his attempt to hit a fox on the road. The driver and the fox die, but Bobby and Mr Summers are more concerned with the death of the animal than that of the human. Here we are presented with the simplistic concept that people who do bad things are bad people and deserve to die, as Mr Summers does not seem at all upset about the man who has just died. This is reinforced by his later absolutist statement, “Good people don’t kill animals”.

Cars are presented as an absolutely evil force, as Mr Summers claims, “The car is a killing machine, pure and simple.” At the beginning of the film, Bobby states, “The most important thing about me is that I was hit by a car when I was a boy”. Bobby’s accident leaves him with brain damage, causing him learning difficulties and challenges with communication. The superlative statement at the start of the film seems strange, as we would imagine that his car accident should not be a defining characteristic of Bobby, or at least not a desirable one. However it is partly due to these difficulties that Bobby finds comfort in talking to Peter and arguably, why he relates so well with marginalised animals. At the end of the film Bobby is again confronted with the possibility of being hit by a car –The Fat’s Rolls Royce, but this time he evades the collision, resulting in The Fat’s death. The image of the car as the enemy draws a parallel between Bobby and “all the little animals”, because they are connected through the threat of being run down.

Bobby’s innocent and victimised character is vital to his connection with animals, as he, like his fellow creatures is under constant threat from a superior powerful force, and like the animals, needs protecting. This innocence is also central to the Melodramatic practice of ‘pathos’ -encouraging the audience to empathise [3] and relate with the characters on screen, as Jonathon Rosenbaum writes in his review, the film ‘requires…a cultivation, of innocence.’ [4] The viewer, by pitying Bobby’s difficult situation and connecting this with the victimised animals in the film is encouraged to protect them. In this way, Thomas’s use of Melodrama draws parallels with the didacticism of Brechtian Epic Theatre: he aims to force the audience to act on what they have witnessed on screen and instruct them through a moral lesson. [5] In Randy Malamud’s, An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture, he claims that ‘The human being trumps actors of other species’, suggesting that human actors will always have the dominant focus in film. [6] This illustrates a possible flaw in the film’s suggestion that there is a balance between humans and animals, because the Melodramatic method through which the film implores the audience to care about the treatment of animals relies essentially on the viewer empathising with Bobby, the human victim. It is the relationship between the vulnerable Bobby and the animals that leads the viewer to sympathise with the animals. Without human characters, sympathy for the animals would be much harder to evoke.

The film has clear-cut morals and absolutes, but the ‘good versus evil’ dichotomy is called in to question when Mr Summers reveals that he murdered his wife. However it is forgiven because Summers explains that his wife made him harm animals. Summers’ morality is momentarily doubted, but he is immediately justified with his defence that he was protecting animals, reinforcing the absolutist notion that people who harm animals are evil. This may be problematic for many viewers, as the moral message presented is totally uncompromising. In this way, Thomas’s film is unusual in its presentation of animal ethics and morality, compared with other films such as The Misfits (John Huston, 1961) and Kes (Ken Loach, 1969), which maintain a moral message of animal protection, but also accept the difficulty of identifying the boundaries of animal ethics. In The Misfits, the character, Roslyn is outraged by cowboy, Gay’s maltreatment of the wild horses they are hunting and confronts him. She is however confounded by his retort implying that the same horse meat goes towards her pet dog’s diet. So although the morality of killing animals is questioned, it is exactly that -questioned- but not given an absolute answer, as in All The Little Animals. Similarly, in Kes, the young Billy feeds his pet Kestrel mice in order to perpetuate the bird’s survival. The death of the mice is not focussed on cinematically, but the death of the bird is a traumatic focal point . This is because it is traditionally accepted that killing animals for nutrition is less abhorrent than killing animals for the sake of it -as in the case of the kestrel’s killing by Billy’s half brother, Jud. All The Little Animals diverges in its presentation of the flexibility of animal ethics, suggesting that to harm animals is never acceptable, creating its own idea of what it means to have a balance between humans and animals.

Related web pages

All Rovi: https://www.allrovi.com/movies/movie/all-the-little-animals-v162431

IMDB All The Little Animals: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120584/

On genre: https://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/intgenre/intgenre6.html

[1] ‘Melodrama’ definition and etymology, Oxford English Dictionary, OED Online, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/116226?redirectedFrom=melodrama#eid, [accessed: 29.03.2013].

[2] Bratton, Cook, Gledhill, ‘Introduction’, Melodrama: Stage, Picture, Screen, (London: BFI Publishing, 1994), (pp. 1-8), p. 2.

[3] ‘Pathos’ definition, Oxford English Dictionary, OED Online, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/138808?, [accessed: 09.04.2013].

[4] Jonathon Rosenbaum, ‘A Breakthrough and a Throwback’, Chicago Reader, https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/a-breakthrough-and-a-throwback/Content?oid=900117 [accessed: 29.03.2013].

[5] University of Southern Queensland, ‘Brechtian Techniques’, https://www.usq.edu.au/artsworx/schoolresources/mothercourage/Brechtian%20Techniques, [accessed: 04.04.2013].

[6] Randy Malamud, An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture, (Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), (pp. 70-93), p. 76.