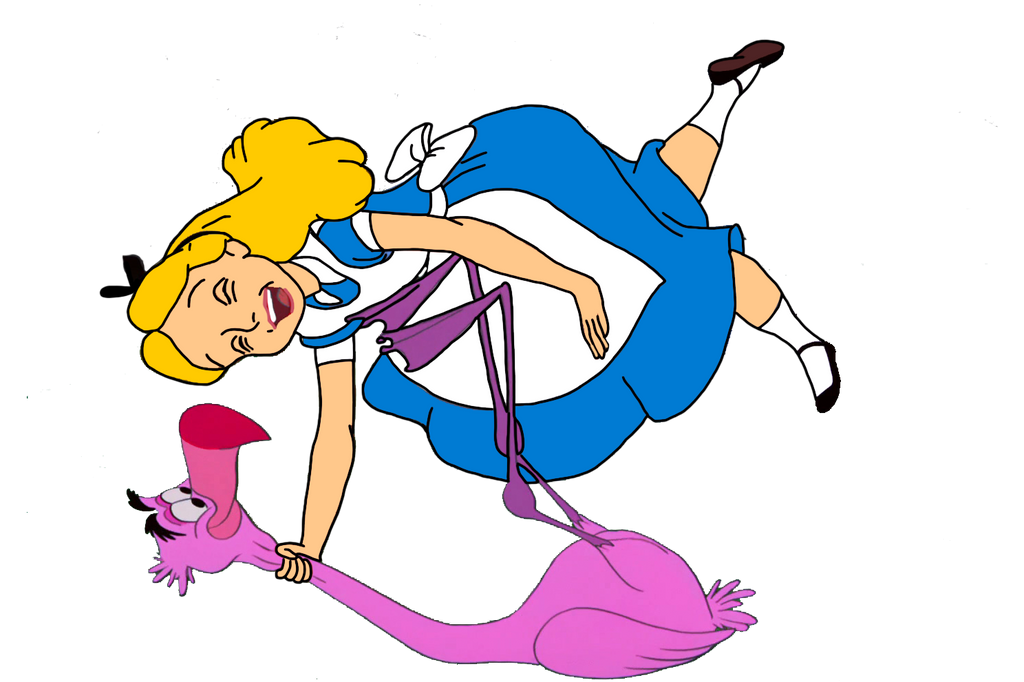

‘Alice in Wonderland’ is a classic story that has inspired many reimaginings. In a scene from the 1951 adaptation from Disney, we witness a surreal game of croquet between Alice and the demanding Red Queen, whose preferred croquet mallets are flamingos and chosen croquet balls are hedgehogs curled into spheres, encapsulating Wonderland’s nonsensical nature that blurs the lines between reality and fantasy.

In the 1951 animated adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s 1865 novel ‘Alice in Wonderland’ by Walt Disney Pictures, a distinctive croquet game featuring flamingos as mallets and hedgehogs as balls becomes a symbol of societal norms and power dynamics in human-animal relationships, reflecting the era’s outlook on animal rights. The whimsy of the scene deviates from the real-world issues depicted in the original text, acting more as a blur than a mirror for its initial arguments. It explores the shifting dynamics between humans and animals, emphasising how Wonderland’s whimsy challenges preconceived notions of animal pet-keeping and domestication.

During the 19th century, societal attitudes toward animal welfare evolved, reflected in legislative measures like the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1849 and the ASPCA’s founding in 18661. Against this outlook on increasing animal rights, the scene’s original purpose transcends its surface playfulness to delve into the complexities of authority and cruelty. Carroll’s original challenges conventional human-animal relationships2, using the croquet game as an obvious example of animal abuse.

However, the 1951 Disney adaptation of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ shifts the focus from challenging cruelty to emphasising whimsical aesthetics. With a decline in the animal rights movement, evidenced by factors such as prevalent circus animals and growing American meat consumption3, this animated version utilises fantastical elements to reduce the mistreatment depicted in the original, highlighting a shift from ethical concerns to aesthetic presentation. The vibrant colours and childlike imagery in the Disney adaptation illustrate how the emphasis on aesthetics influences emotional reactions to human-animal relationship scenarios, diverging from the original’s focus on animal rights and creating a disconnect from reality.

The whimsical atmosphere emphases that the lens through which we view these interactions greatly influences our emotional response. In contrast with the darker tone in Tim Burton’s 2010 rendition, which focused on the intensity of the situation and the very-real threats of Wonderland, the visual aspects of the croquet game take the attention to create a comical tone. Vibrant colours, childlike music, and mischievous behaviour, like the hedgehog’s yawn, strip away the depth present in the original text, creating a more playful narrative.

Characterised by vibrant colours and surreal design inherent in its animated genre, the bright pink of the flamingos contrasts with the vivid green and purple of the hedgehogs, creating a visually stimulating scene that feels lighthearted to watch. If portrayed in a live-action realist format, the same scene would be uncomfortably different. This deliberate choice to prioritise imagery over message serves as a commentary on the potential dangers of obscuring real-world issues, such as the exploitation of animals for entertainment.

Despite its 1865 publication, ‘Alice in Wonderland’ continues to permeate throughout culture, and while some elements of notorious stories fade from memory over time, see ‘Wuthering Heights’ entire second half, the croquet game in ‘Alice in Wonderland’ stands as a remarkable exception. In fact, it’s seen not only in full adaptations like Tim Burton’s 2010 movie of the same name but also in other cultural references like artwork, dance, music, and fashion. This enduring influence emphasises the scene’s significance in challenging societal norms and power dynamics within human-animal relationships, reaching far beyond the confines of the original text. For example, British Vogue noted how Lewis Carroll’s novel “has inspired everyone from Comme Des Garçons’s Rei Kawakubo to Vivienne Westwood”4 (who designed a special edition cover of Carroll’s book in 2015). In fact, it served as a focal point for American Vogue’s December 2003 editorial by Annie Leibovitz which showed designer John Galliano as the Queen of Hearts and Alexis Roche as the King.

Authoritarian dominance is vividly exercised over the animals by the Queen of Hearts, mirroring her control over Wonderland. The Queen’s abusive rule is unmistakable in this bizarre croquet game, with her wielding animal subjects as instruments of her will. Notably, the contrasting reactions of the animals to Alice and the Queen unveil a powerful narrative layer. The flamingos remain rigid and obedient in the hands of the Queen, embodying their servitude to her despite her evident cruelty. In stark contrast, these same creatures misbehave and trick Alice, who is earnestly attempting to avoid endangering them both, revealing a nuanced loyalty that transcends their role as mere tools.

Drawing parallels with real-world scenarios, such as the mistreatment of animals on Flamingo Beach in Aruba for social media virality, underscores the scenes’ initial commentary. While we’d expect mistreated animals to retaliate against their abusers, both the flamingos in fictional Wonderland and those in real-world Aruba maintain a composed demeanour, shedding light on the intricate relationship between animals and authoritative figures that prevails outside of the public’s concern for animal rights.

In a 2017 article, Caroline McGuire noted that “Many believe that the flamingos have had their wings clipped, which would explain why the birds don’t migrate like the animal usually does,”5 suggesting that resistance for the flamingos would be seemingly pointless, much like their Wonderland counterparts who risk losing their heads.

Despite Alice’s attempts to command obedience, the animals remain loyal to the Queen and the scene becomes a reflection of power struggles and misunderstandings as Alice, in her frustration, resorts to aggression, attempting to force compliance. Unbeknownst to her, the animals’ loyalty lies with the Queen, and their apparent misbehaviour is part of the Queen’s desire for their antics. The scene unravels layers of tension, revealing the intricacies of Alice’s evolving relationship with the Wonderland creatures.

Her anger both at this confusion and of the animal’s unwillingness to behave turns to physical aggression which shows the tension in Wonderland but also shows Alice as being, debatably, no better than the Queen who also abuses the animals. Alice’s frustration and resorting to physical aggression showcase the tension inherent in Wonderland and raise ethical questions about her behaviour mirroring the Queen’s, prompting contemplation on the potential for individuals to perpetuate harmful actions in a system that encourages such behaviour, even unintentionally.

The threat of execution and the subsequent conformity of both animals and humans underlines the coercive nature of authority, prompting reflection on the fine line between submission and rebellion in human-animal interactions, mirroring broader societal power structures. Alice plays the game out of fear of how the Red Queen would react, having already heard her sentence three of the players to be executed for having missed their turn – but the confusion of the game meant that she never knew whether it was her turn or not.

The croquet game in Disney’s ‘Alice in Wonderland’ transcends its whimsical surface, becoming a symbol of societal norms and power dynamics in human-animal relationships that reflect the era’s outlook on animal rights through visuals and whimsy. The Queen’s authoritarian rule symbolises real-world struggles for dominance, while Alice’s attempts to navigate the complexities of human-animal relations unveil the nuances of empathy and conflict.

- Susan Pearson, “‘The Inalienable Rights of the Beasts’: Organized Animal Protection and the Language of Rights in America, 1865-1900,” Northwestern University, 2006, https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/law_culture/48. ↩︎

- Anna Kérchy, “Alice’s Non-Anthropocentric Ethics: Lewis Carroll as a Defender of Animal Rights,” Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens, December 2018,

https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.3909. ↩︎ - Eliza Barclay, “A Nation Of Meat Eaters: See How It All Adds Up,” Morning Edition, NPR, 27 June 2012,

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2012/06/27/155527365/visualizing-a-nation-of-meat-eaters ↩︎ - Rosalind Jana, “Why Alice In Wonderland Is One Of Fashion’s Most Enduring Muses,” British Vogue, 12 June 2021,

https://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/alice-curiouser-and-curiouser. ↩︎ - Caroline McGuire, “Popular flamingo Instagrams might be result of animal cruelty,” New York Post, 23 May 2017, 3:55 p.m. ET, https://nypost.com/2017/05/23/popular-flamingo-instagrams-might-be-result-of-animal-cruelty/. ↩︎