Following the great success of director Nick Park’s A Grand Day Out in 1990 and 1993’s The Wrong Trousers, eccentric inventor Wallace and his canine companion Gromit returned in 1995 with A Close Shave. The action begins as the duo – now running a window cleaning service – have their breakfast interrupted by Shaun the sheep, who has escaped from a mysterious lorry. The pair are then called to clean the windows of Wendolene’s wool shop, whose stocks are inexplicably full in spite of widely-reported sheep-rustling incidents. Whilst Wallace is distracted by Wendolene’s charms, Gromit is framed for the recent rustling by the true criminal, robotic dog Preston, and in freeing a flock of sheep Preston had trapped, Gromit inadvertently locks himself in Preston’s lorry to be driven straight to jail. With the help of Shaun and the other sheep, Wallace stages a dramatic jailbreak, before they discover the true extent of Preston’s evil.

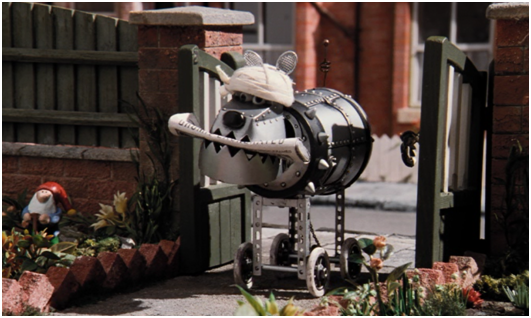

A Close Shave fits snugly within the conventions of the family comedy genre. Its wide-mouthed clay figures have a cartoonish appeal; whilst the film’s fast pace and imaginative climax will keep even its youngest viewers entertained. Meanwhile, the richly detailed scenery, bringing to mind the romantic notion of a quaint northern town has more than enough to reward multiple viewings for older audiences. What’s more, beyond the initial pangs of nostalgia, viewers can see an incredible level of detail in every set in the film. The sets are delightful to a family audience, their vivid detail creating a sense that this is a real world in which we can lose ourselves. Yet, the visible fingerprints on the characters illustrate the self-awareness of the filmmakers – they want us to know that this world has been created by humans, which for older viewers can only add a sense of wonder when they consider the sheer amount of work involved. Plus, the entire film is full to the brim with puns and wordplay. In fact, several examples have been mentioned here already – Wendolene might be considered to pun on ‘windolene’, referencing Wallace and Gromit’s business; Shaun’s name is an allusion to his close shave in Wallace’s knit-o-matic; whilst the name A Close Shave is itself a pun, referring both to the shorn sheep and the characters’ narrow escape from catastrophe at the end of the film. This self-awareness in the film’s finer details gives A Close Shave such richness, which carries through into the story. In its chase sequence, the film strays into the territory of adventure films, with twists aplenty as the tension mounts to an ambitious finale, finally resolved by an unlikely hero in Shaun. However, the filmmakers are careful to keep comedy at the film’s heart, with much of the action actually playfully parodying the established adventure genre. Park has acknowledged that the scene in which Wallace suits up to a stirring soundtrack pays homage to Thunderbirds. [1] The mechanism used to start the engine of Wallace’s motorcycle is nothing more than a boot on a pole – his inventions are of a comedic, friendly kind.This nostalgia for a simpler time permeates the film, not only contributing to its charming family-friendly humour, but also providing an interesting counterpoint to the ultra-modern ‘cyberdog’ Preston – the clear antagonist – as the film comes to a moral conclusion on the effects of modern industry in the countryside.

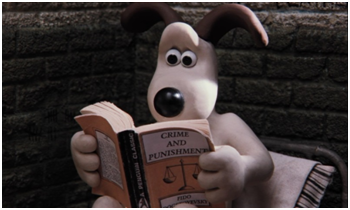

Considering they are officially pets, Gromit and Preston enjoy special status in the film. Gromit’s first scene in the film sees him sitting up in bed in a fully furnished room, knitting a scarf, with a bookshelf in the background containing a tome on ‘prehistoric life’. Meanwhile, Preston sits in the front of the lorry outside the duo’s house, and is later seen driving it himself. This is instantly juxtaposed by the figure of Wallace, also in bed, but with no clues about his character other than the framed portrait of some cheese on his wall. These are seriously smart animals, and from the beginning we are bound to expect much of them.

However, it appears that Gromit and Preston are rather unusual in this respect. The other animals which feature heavily in A Close Shave – the sheep – behave exactly as expected. Comically, they are able to form acrobatic formations during the chase scene, but they do so together and without hesitation, no individual standing out, with the exception of course of Shaun. Gromit and Preston, on the other hand, do not look like ordinary dogs. [2] On Gromit’s morning newspaper, though, we see the headline ‘Jack Russell chews cricket ball!’, accompanied by a picture of a furry, traditional-looking dog.

In another example of the humour to be found in the background of the film, the headline references the cricketer Jack Russell, who played for England in 1980s and 1990s. Seeing Gromit read a newspaper is not directly connected to the film, but it adds to its broad appeal, illustrating the filmmakers’ efforts to give the film the layers which are vital to a successful family comedy. However, the newspaper remains striking for another reason. The intelligent, domesticated Gromit would surely never do such a thing as chew a cricket ball, but the implication that traditional, non-anthropomorphised dogs exist in this world heightens Preston and Gromit’s own privileged positions. Unfortunately for him, Gromit must also endure the hardships of a humanised life, and whilst he is on the run from prison, Wallace informs him that he will be ‘hunted down like, well, a dog!’. Gromit responds with a look of disdain, evidently considering himself somewhat more important than that.

The conflict between Gromit and Preston’s heightened intelligence and their enduring position as mere pets is troubled by the film’s resolution, which sees Gromit reverting to subservience, despite proving his innocence and getting Wallace and Wendolene out of a sticky situation; and Preston paying dearly for his attempt to gain economic independence, regressing to four legs as punishment for his industrial ambition.

Still, the filmmakers haul themselves out of this difficult situation. Though Gromit returns to normal life, which presumably includes serving Wallace breakfast every morning, he does so out of loyalty. Alongside his unusual privileges, Gromit represents the inherent goodness of the dog as ‘man’s best friend’, but of course, thanks to the ubiquitous ‘beware of the dog’ sign, it is also natural to consider dogs dangerous and violent – like Preston. In this way, Preston and Gromit seem to be two parts of the same whole. However, Preston is not natural. He is the product of modern, mechanised industry, which the film actively opposes. Whilst in jail, Gromit receives standard dog food in a bowl, in what is clearly a “dehumanising” experience for him. Preston wants to move into the industry which produces this food, giving his product the stark name of ‘Preston’s Dog Food’. It is industrial and cold, in clear contrast to Wallace’s enterprises, which include the ‘knit-o-matic’, an invention which demands nothing more of animals than a haircut. So, Preston’s downfall is entirely deserved for his unscrupulous efforts to force out the smaller, friendlier businesspeople of his quaint little town. Additionally, it is Gromit’s cooperation with Shaun, in spite of the threat Shaun poses to Gromit’s position in the household, which defeats Preston, proving Gromit’s “pedigree” in opposition to Preston’s selfishness. Shaun, meanwhile, never needs to stand on his hind legs to prove his heroism, striking a blow against Preston’s disregard for animal agency.

All the while, the film is absolutely aware of the absurdity of feeling so deeply about plasticine models. They have visibly (and intentionally) been manipulated by human fingers, and their minutes of motion on screen have taken days in the studio to realise. Moreover, the music provokes a response in viewers which is seemingly inappropriate for the simple-minded Yorkshire folk on screen. As Nick Park told the South Bank Show, ‘it all seemed like Hollywood, and yet it was just plasticine models’. [3] In the DVD commentary, animator Steve Box joins Park to say that the music ‘contributes to the comedy’, to make it seem ‘as if they’re real characters’. [4] They were even concerned that when Shaun ends up in the knit-o-matic, the music was ‘too dark’, making the sequence ‘extremely cruel’. [5] The filmmakers play a game with the viewers, pushing us to invest in the characters through the immense detail and the genuinely moving music, whilst also ensuring that the events and characters are too preposterous to be taken very seriously. By balancing the tension of ‘real-world’ problems with artistic license, the filmmakers keep A Close Shave entertaining enough to maintain its status as a light comedy, yet rich enough to make it rewarding to adults and children alike.

A Close Shave sees animals presented as smart and capable beings. Part of the film’s humour comes from the contrast of the cluelessness of the human characters – Wallace in particular – with the intelligence of the mute animals. Whether evil or virtuous, they prove themselves to be smart problem-solvers, and crucially, non-reliant on humans, despite being considered as pets. The heightened agency of these animals enables the film’s deeper theme of the conflict between natural, unthreatening enterprise and aggressive, mechanised industry. The central opposing figures of Gromit – faithful to Wallace and accepting of the potentially threatening Shaun – and Preston – selfish, disloyal, and quite literally robotic in his behaviour – enable the filmmakers to express support for small, local entrepreneurs in a world increasingly driven by big business. Indeed, Wallace’s passion for Wensleydale cheese led the creamery which produces it to successfully ask Aardman Animations to endorse the real life product, saving the creamery which produces it from collapse. [6] The quaint settings and visible human touch on the plasticine models reinforce the film’s sentimental support of small-time business, whilst also creating a fun, cartoonish aesthetic to appeal to all with an eye for the quirky. To borrow from Wallace’s vocabulary, the success of A Close Shave‘s balancing act between genuine, realistic concerns and a commitment to family-friendly might best be described as ‘cracking’.

Pixar’s Monsters, Inc., another family comedy, shares a distaste for aggressive business with A Close Shave, though with a different resolution. The film sees the roles of animals – or, more specifically, monsters – and humans reversed, with humans the commodities; their screams utilised for energy. The evil Randall attempts to ‘revolutionise the scaring industry’ with a machine which efficiently extracts screams from kidnapped children. In a moment of self-awareness which Nick Park would be proud of, Randall’s henchmonster, Fungus, explicitly tells us that such methods are wrong, saying ‘I’m not allowed to fraternise with victims of his evil plot!’. A Close Shave solves the problems of mechanised industry by allowing the triumph of small enterprise over Preston’s industrial-scale sheep mincing scheme, with respect for animal agency healthier than ever. Monsters, Inc., however, sees its human character leave the monster world, returning to commodification. Their work becomes friendlier, the monsters realising that laughter produces more power than screams, but the characters’ triumph comes in restoring economic security to the company. Ensuring that audiences do not leave with this somewhat uninspiring conclusion, Monsters, Inc., like A Close Shave, never strays far from family entertainment, and when Sully reconciles with his quasi-pet human Boo, the sentimentality that has made both films so enduringly popular is restored.

[1] Nick Park and Steve Box, ‘Commentary’ for ‘A Close Shave’, Wallace & Gromit: The Complete Collection, dir. by Nick Park, written by Bob Baker and Nick Park. [DVD]. (London: 2 entertain Video, 2009).

[2]Though he is apparently recognised by most kennel clubs as a beagle, there is no clear evidence to support this.

[3] The South Bank Show. (ITV, 26th November 2006) [accessed 17th November 2014].

[4] Nick Park and Steve Box, ‘Commentary’ for ‘A Close Shave’, Wallace & Gromit: The Complete Collection, dir. by Nick Park, written by Bob Baker and Nick Park. [DVD]. (London: 2 entertain Video, 2009).

[5]Nick Park and Steve Box, ‘Commentary’ for ‘A Close Shave’, Wallace & Gromit: The Complete Collection, dir. by Nick Park, written by Bob Baker and Nick Park. [DVD]. (London: 2 entertain Video, 2009).

[6]‘The Amazing World of Wallace & Gromit’, Wallace & Gromit: The Complete Collection, dir. by Nick Park, written by Bob Baker and Nick Park. [DVD]. (London: 2 entertain Video, 2009).

Bibliography

Abbott, Kate, ‘How we made Wallace and Gromit’, The Guardian, (London: Guardian News and Media, 2014), < https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2014/mar/03/how-we-made-wallace-and-gromit>

Langford, Barry, Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005)

Filmography

Box, Steve and Park, Nick, ‘Commentary’ for ‘A Close Shave’, Wallace & Gromit: The Complete Collection, written by Bob Baker and Nick Park. First broadcast 1995 [DVD]. (London: 2 entertain Video, 2009)

Docter, Pete, Monsters, Inc., written by Andrew Stanton and Daniel Gerson. (Disney Home Entertainment, 2002)

Park, Nick, ‘A Close Shave’, Wallace & Gromit: The Complete Collection, written by Bob Baker and Nick Park. First broadcast 1995 [DVD]. (London: 2 entertain Video, 2009)

The South Bank Show. (ITV, 26th November 2006) [accessed 17th November 2014]