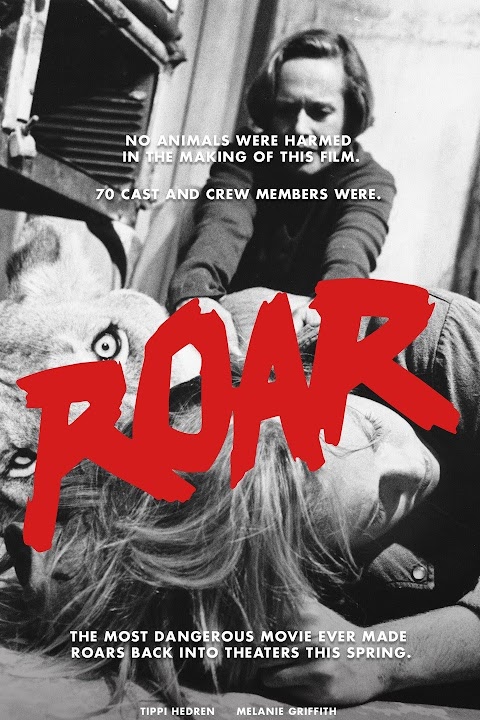

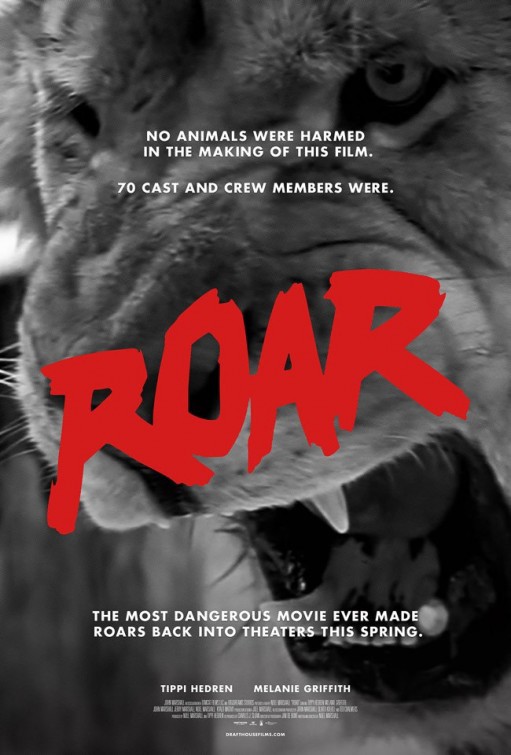

“No Animals were harmed in the making of this film. 70 cast and crew members were”.

A film tagline that instantly grabs your attention. The Drafthouse re-release in 2015 coined this moniker for the 1981 box-office blunder[1] “Roar”, which lacks plot, conventionality and, as the curious tagline suggests: a lack of safety measures for the actors and crew. Through the films lack of traditional ethical principles, we as an audience get to see filmic interactions with lions, tigers, and other safari creatures up close and personal in “one of the most dangerous movies ever made”[2]

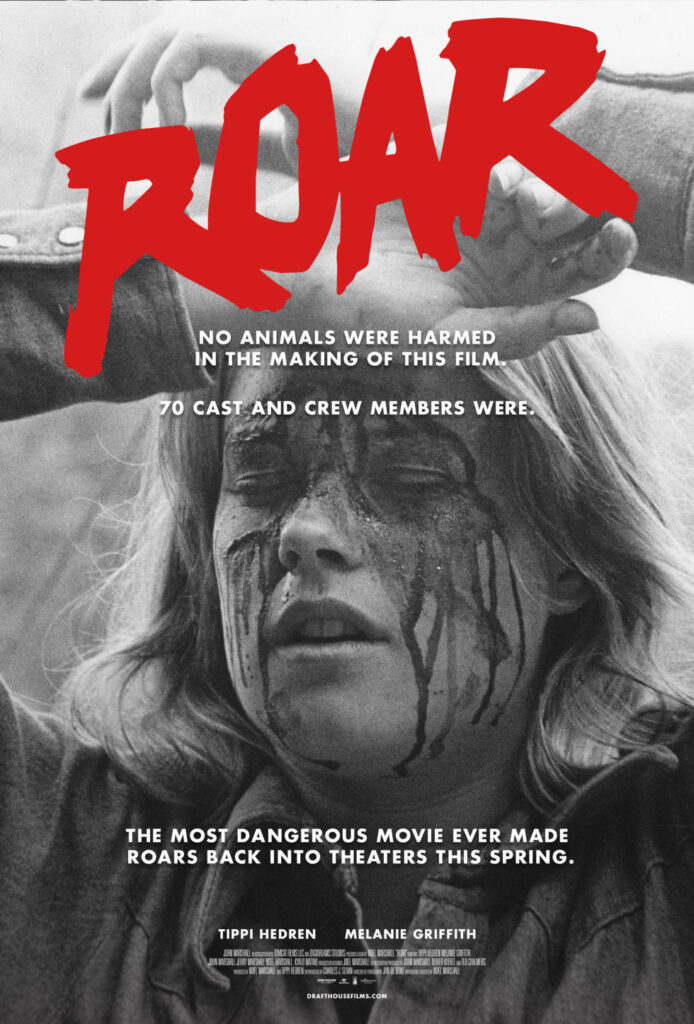

Perhaps, in some cases, too close:

In Figure 2, we see actress Melanie Griffith being mauled by a Lioness, and her film mother, Madeleine, (also real-life mother, Tippi Hedren) attempting to pull this big exotic cat off of her suffering daughter through desperate sobs, screaming “Get off of her!”, while we hear uncomfortable weeping from Griffith. The then fourteen-year-old actress had to get reconstructive surgery on her face after the clawing.[3](Figure 3)

Every sequence with the lions was improvised and needed to be recorded with four cameras[4], evident in this scene with the opening shot omitting feelings of uncertainty with the person operating the camera appearing to be unsure of whether to focus on Griffith or Hedren. This imbues the scene with an underscore of disquieting spontaneity which, in turn, makes audiences fear for the safety of the actors involved. In many films involving wild animals, particularly lions, other methods are used in order to ensure the protection of the cast and crew, such as animatronics in “Jumanji” (1995), (figure 4), which offers a sense of security for the audience in knowing that every shot was meticulously planned, not only cinematically, but also in considering the dangers involved with utilising real-life animals for effect, demonstrating concern for actors, crew and even the audience. Melanie’s attack in “Roar” proves to be a showcase of crossing traditional film-making ethics and boundaries. (Figure 5).

Director Marshall appears here to subvert the frequent narrative of prioritising actor safety over animals, as he allowed these wild animals autonomy in their natural behaviours, which, as we can see in this scene, leads to disastrous results. (Figure 6). This autonomy, however, could only occur through the aforementioned improvisation, which can be seen in Hedren’s visceral and impulsive reaction in pulling the lioness’s tail in a futile attempt to save her daughter being attacked.

After grabbing her tail, the lioness retorts with a disarming gaze and signals Madelaine (Hedren) with a bite. This startles her and she backs away into the corner of the room. These reactions appear to be genuine, making the scene all the more horrifying as it serves as confirmation that these attacks are real, giving meta-filmic elements to the narrative, leaving viewers questioning the welfare of the cast and crew instead of viewing them as characters in a scene. The implications of potentially putting Griffith’s life at risk for an unfiltered view of human and animal interactions highlight the complex ethical dilemmas at play in the film and questions the delicate balance between animal wellbeing and human safety. The wild animals had freedom, but the actors and crew arguably did not.

References:

[1] Ros Tibbs, The 1980s Movie That Saw 70 People Injured by Lions,” Far Out Magazine, 2022 <https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/roar-1980s-movie-70-people-injured-lions/>.

[2] Sean Donovan, “Animalistic Laughter: Camping Anthropomorphism in Roar” The Cine-Files, Issue 14, 2019 p.3

[3]Jen Yamato, “Exclusive: Watch a Lion Maul Melanie Griffith in ‘Roar,’” The Daily Beast, 2017 <https://www.thedailybeast.com/exclusive-watch-a-lion-maul-melanie-griffith-in-roar>.

[4] Randolph Sellars, Surviving Roar: The Most Dangerous Film Ever Made, Stage 32, 2014

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Roar (1981) Directed by Noel Marshall, Filmways Pictures, accessed via YouTube.

Secondary Sources:

Donovan, Sean, “Animalistic Laughter: Camping Anthropomorphism in Roar” The Cine-Files, 2019

Sellars, Randolph, Surviving Roar: The Most Dangerous Film Ever Made, Stage 32, 2014

Tibbs, Ros, “‘Roar’: The 1980s Movie That Saw 70 People Injured by Lions,” Far Out

Magazine, 2022 <https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/roar-1980s-movie-70-people-injured-lions/>

Yamato, Jen, “Exclusive: Watch a Lion Maul Melanie Griffith in ‘Roar,’” The Daily Beast, 2017

<https://www.thedailybeast.com/exclusive-watch-a-lion-maul-melanie-griffith-in-roar>