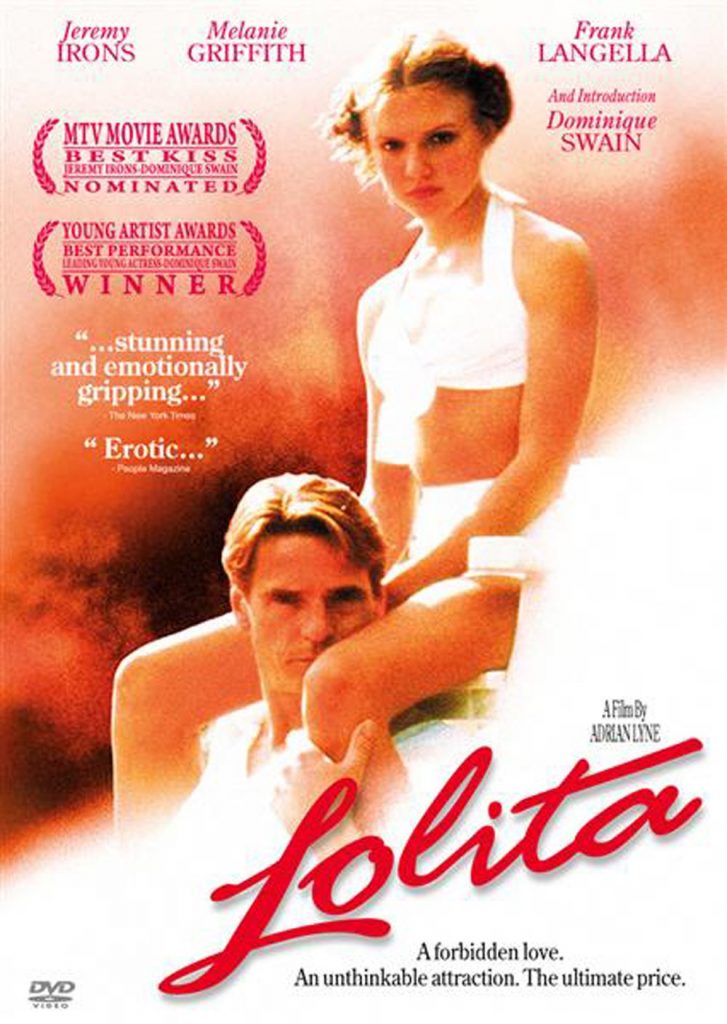

‘Lolita’ (dir. By Adrian Lyne, 1997) is based Vladimir Nabokov’s novel of the same name. It follows the story of Humbert Humbert and his twelve year old step daughter Dolores or as he nicknames her, Lolita. The relationship between these characters is far from the idealistic father-daughter relationship, as Humbert reveals his paedophilic motive. The themes of carnal desires and basic instincts are prevalent throughout the film, as male characters fight for dominance in order claim a submissive female as their prize. Though the film does not rely on the interaction between non-human animals and humans to carry its plot, there are distinct moments where these interactions underpin central themes; most notably the relationship between dominance and submission, and predator and prey.

The first time the audience views a scene including a non-human animal and human relations is the time that Lolita, and the audience for that matter, meet Clare Quilty. Quilty is depicted as a predator throughout the film, as he hunts father and daughter, and his first appearance does not detract from this. The notion of a relationship between predator and prey is inherently linked to the relationship between humans and animals. Humans naturally adopt the role of the predator, even in everyday life through the consumption of meat and as a captors through the ownership of pets. In this sense, the interaction between the predator Quilty and his prey Lolita is brought together through Quilty’s spaniel. The breed of dog also plays a crucial role in the audience’s perception of the relationship between the characters. Lyne specifically uses a King Charles spaniel, as the breed is renowned for its friendliness and ability to remain unfazed by children. The familiarity and cuteness of the dog invites the audience and Lolita into a safe and secure interaction insinuating that dogs are in fact like their owners.

Lyne uses a warm toned colour scheme throughout this scene, which lulls the audience and Lolita into a false sense of security. The earth tones of the woodwork combined with the yellow lighting creates a homely effect and installs a sense of trust between the figures within the scene. This is not the only way that colour is used, as both Lolita and the unnamed spaniel share the same rich auburn hair colour. This implies that both characters are a reflection of the other. The spaniel brings out the forgotten childlike part of Lolita’s personality, having been forced into an adult world of intimate relationships and parental death. Being thrust into this environment at the age of twelve, Lolita would not have had a chance to explore and understand her sexuality which gives rise to her vulnerability being exploited. This is shown through her making direct eye contact with the dog, whilst being in the hunched position, which from her position could be seen as a display of dominance over the dog; but from the perspective of Quilty, it is a direct sign of submission. This is further illustrated when the audience witnesses her holding onto the animal’s shoulders and simultaneously snapping at him and stroking him. Here, her actions reinforce the aspect of her personality that remains a child, unaffected by the situation she has found herself in. She gives the dog mixed messages, which she unknowingly does with every other male in the film, by confusing childlike curiosity with affection. These acts are not inherently sexual, but due to the unreliable narration of Humbert, her behaviour is constructed in such a way that the audience takes them to be.

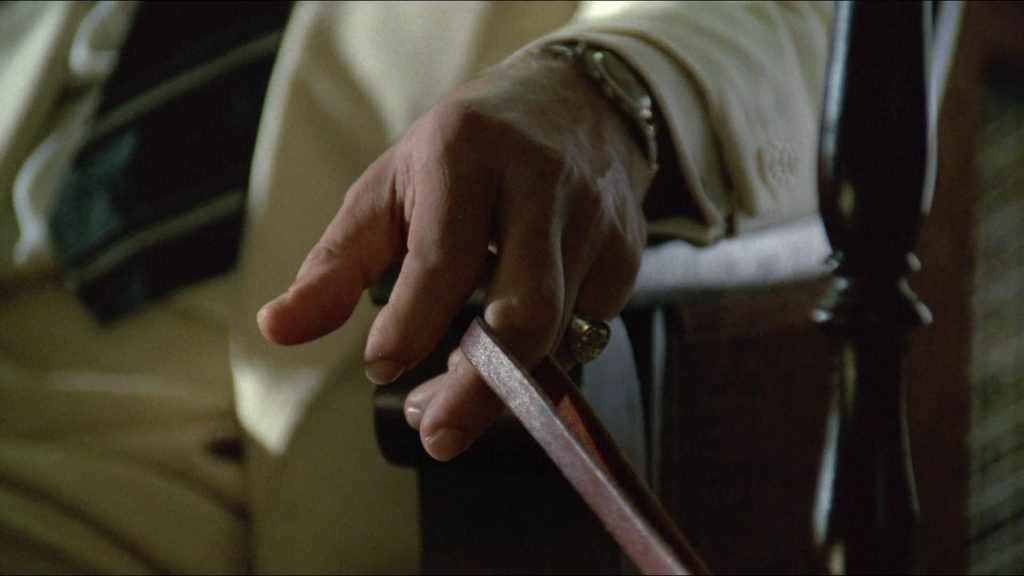

This reflection continues, as both are kept as pets to entertain their masters. Lolita appears to escape the entrapment of being a pet – she is not physically restrained, like the spaniel is by its lead. The mise-en-scene of the scene is influential here, as the lead is wrapped around Quilty’s finger which alludes to Lolita also being wrapped around his little finger later in the film. The lead is repeatedly in focus which reinforces this concept that no matter how much Lolita strays from her master, he will always be in control to pull her back. Once again, the dynamics of a predator/prey relationship are at work here, as Quilty displaces his self-control onto the dog via the tool of the lead. The lead is used as a visual representation of restraint, as Quilty allows the dog to stray from his side, but he never lets it go too far. This mimics Quilty’s behaviour throughout the film, as he plays a game of give and take whilst chasing Lolita and Humbert. This reading however, is not apparent in the first viewing of the film. Therefore Lyne implies that through the eyes of Humbert, who knows and has relived the story many times, certain behaviours can be viewed as sexual when they are not.

The use of off screen space, by which the audience only hears the voice of Lolita’s original master, Humbert, presents the lack of a challenge to male dominated authority. The camera provides a pedestal movement, advancing from Quilty’s black and white shoes, which generate the familiar predatory colour scheme of killer whales; right up to his face, which is obscured by a lamp. This mimics Lolita’s first sighting of her predator, from her placement on the floor with his already captured prey, stating that Quilty has won the battle for dominance at this point. This scene provides the clearest display of battles for dominance throughout the film, and the use of the animal is crucial to its conviction. The interaction between the female child and the animal highlights the vulnerability of unexplored female sexuality by comparing the female to a restrained pet. Furthermore, it also demonstrates the level of control in regards of the self and situation that is required by the adult male in the fight for dominance.

Bibliography

Lolita, dir. by Adrian Lyne (Third Row Center Films/Showtime, 1998) [DVD]

Photos found on: http://kissthemgoodbye.net/movie/thumbnails.php?album=367&page=4

http://www.globalresearch.ca/100-death-rate-for-baby-killer-whales-along-the-canadian-west-coast-in-the-past-3-years/5419272