Of course, it is odd to gaze from social isolation into absolute claustrophobia while still in a lockdown: Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia’s twisted dystopian Sci-Fi thriller El Hoyo (in international release The Platform) is about being trapped in a large concrete construction that resembles a maintenance hole. It is also about social hierarchies constructed as a result: “Crap” always flows from the top down, the film teaches us incessantly over its hour and a half. Inmates of a vertically piled up prison, with two inmates on each floor, fight for bare survival due to the lack of food for the entire population. An extensive buffet of the finest hearty and sweet food travels, from top to bottom through the middle of the cells, in a limited amount of time. On multiple occasions throughout the movie, animals are only used and disposed of by humans.

The dystopian Sci-Fi Spanish production starts with what looks like the kitchen of a top restaurant; the Jamón is carefully cut, the cakes draped with flair. After just a few seconds of this intro, we find ourselves in a dreary place with two strange characters, “Level 48,” as the older one (Zorion Eguileor) puts it. “What’s upstairs?” asks the protagonist Goreng (Iván Massagué). “Level 47, of course,” is the answer, and for a while, you fiddle with this kind of limited knowledge in El Hoyo until you gradually grasp the concept: There are about 300 levels within the shaft, there are two people on each one, sometimes they wake up on a completely different, arbitrarily chosen level. It is a social experiment through which the viewers follow Goreng in various personal constellations and on different floors. How well he is doing – how much of the top restaurant food he receives from above – depends on how high up he is. The movie portrays various animals. There are multiple sequences of lobsters, snails, and meats, either prepared or set on the moving platform’s table. The inmates on the prison’s top floors have an abundance of food and waste it or purposefully defecate or pee on it for the bottom floors to consume. The consumption of snails is portrayed as a symbolic metaphor for cannibalism. There are also sequences of cows’ and pigs’ skulls.

Therefore, it is meant allegorically: the film insists that it is about food, the pit is itself a Hellmouth into which the characters wander. It is about social strata, questions of solidarity, and egoistic interests: eating or eating. In this constellation, certain ones then behave all too “human. ” Of course, they gorge themselves when they stand in front of a magnificent buffet – what happens to those below them doesn’t matter to them, at least for the moment, because they were already down there; finally, they are up on top. Even the intellectual well-meaning person can only evade such a dynamic until he has looked into the other side’s situation, as the protagonist’s journey shows all too impressively. In El Hoyo, distribution is random; everyone draws their lot in the lottery, nothing is left of the Protestant idea of prosperity. Nevertheless, that does not make the upper classes any more solidaristic.

Naturally, when the setting consists of dark and thick concrete walls, the film has to depend on its acting, music, and camera angles that bring out the very best in the simple mise en scène. Moreover, all in all, it is so gripping that it gets on one’s nerves, especially on the lower floors, where maggots and other unpleasant things have to be eaten in order to make it back up the ladder alive. These aspects demonstrate the inmates’ agonies, and the tension is maintained despite dialogue-heavy and minimalist sets.

Various animals are present a lot throughout the movie. Whether they are kept in an aquarium, being prepared for consumption, or as a pet to one of the inmates, one thing stays consistent in all these portrayals: all the animals do not have any agency, and their emotional depth is disregarded. The movie begins in the kitchen on the uppermost level of the prison. That is where the food (everything consists of meat or animal products) is prepared. The head chef is walking through the aisles, seeing if everything is being prepared correctly. He walks past pieces of mutilated cows’ legs hanging by the ceiling and bloodied pig skulls and head on the table, ready to be chopped up for the meals. The camera zooms in on the other chefs as they are cutting up the meat with blood splattering. We do not witness them alive but only see their flesh being cut up, cooked, and assembled to look nice. Dramatic orchestra music is played in the background throughout this film, with the sound of violins being emphasized. The whole scene is quite dark and dull in color. The director incorporates many close-up shots of the meals and wide angles of the head chef in a setting full of dead animals. This scene invokes an uneasiness in the viewer because its focus is not on making the food look appetizing but instead on criticizing the overconsumption of animals.

Another sequence shows the preparation escargot. The scene starts by showing snails alive and moving, then jumps to the snails being washed, sauteed, and then drenched in sauce. Again here, a similar dramatic orchestra is playing in the background. In some scenes, the hand-held camera is a bit shaky, which channels the grim and dystopian state of the movie. Snails are also a symbol for cannibalism in the film, with them being present when cannibalism is being performed, and a person is being consumed.

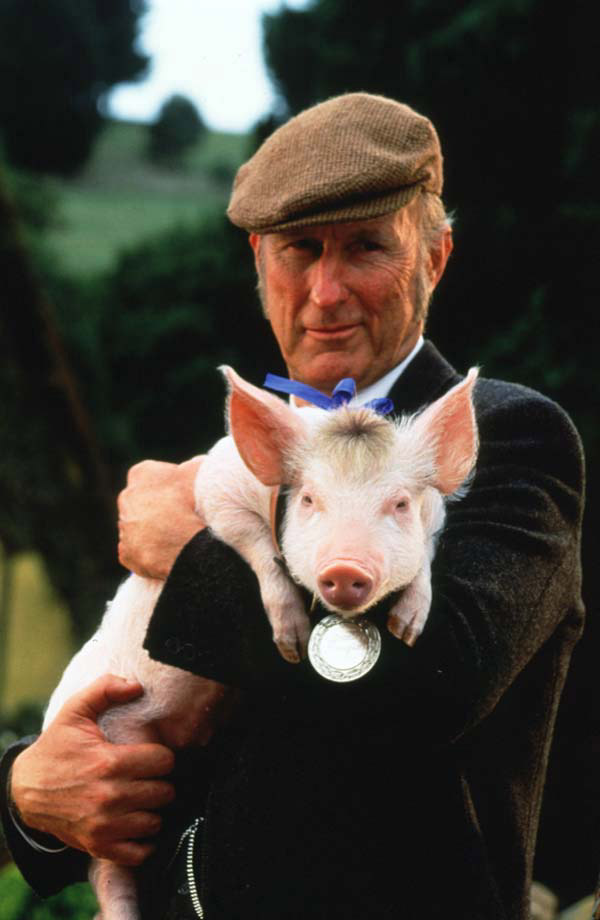

Imoguiri with the Dachshund

One disconcerting scene depicts a dog protected by its owner from the other inmates who might harm it to survive, being murdered. In this scene, the Dachshund is sleeping in its owner’s bed before being murdered and mutilated by one of the inmates because. The dog’s emotional depth or agency is not recognized in the film, nor are they the focal point of this scene because the director tries to raise more awareness of his social commentary of this dystopian world. The shot suddenly cuts away as it is being mutilated and then cuts to a gory close-up shot of the dog’s mangled and dismembered body. This cutaway shot is undoubtedly required because the film is not using a CGI dog to cut back on the film budget. It is also illegal to mutilate a dog on camera. The cutaway has its stylistic effects. This scene in the dark with a blood-red filter on the shot stirs dread in the pit of the viewer’s stomach. It worsens the impact of the murder of the dog by letting us know what is happening without the catharsis of actually experiencing it – so the viewer is only left to wonder about what has happened to the Dachshund. Off-screen, the sobs of its owner can be heard.

Ultimately, the dog was given no agency and no other purpose but to be used by various people. The scene, very dimly illuminated, was shot in close-ups, medium shots, and wide angles. The sequence rapidly jumped from the dog being alive in bed to the dead dog, emphasizing how fragile an animal’s life is. This also invokes uneasiness and distress in the viewer. The sound score is quite unnerving and haunting.

Director Gaztelu-Urrutia creates a nightmarish, claustrophobic atmosphere through the conception of the setting, in that the place of action is both narrow and wide. The inmates can look up and down the prison. These images show the seeming endlessness of the structure. The fact that no one knows how big the tower is only adds to its grandeur. Simultaneously, space and room to move within the cells are severely limited by the hole in the middle, as is the room to maneuver concerning the platform due to the time limit on how long it stays on one level and the food available. “There is simply never enough space or time for the characters to do or say what they need to.” The film is designed with a minimal aesthetic through the cells’ furnishings and is primarily a dark stone gray. “If there’s color, it’s usually dark red or blue.

Animals being prepared for consumption in the kitchen.

A color as simple as plain green stands out for the audience. The confinement also leads to an extreme closeness, expressed in camera proximity. In the cell, the protagonist is shown for the first time through a zoom so strong one can count his eyelashes. Furthermore, there is no reason for cinematographer Jon D. Dominguez to take a step backward – the set is a gray box, the daily feeding disgustingly shot with extreme close-ups on dirty fingers stuffing their mouths with rice to the sound of smacking. Even a fantasized love scene between Goreng and an inmate zooms in on their tongues. The use of bodily fluids, literally urinating or defecating on each other, also adds to the disgust through grossness that makes even the most basic human functions seem vomit-inducing. “The soundtrack smacks with the music of sick bodies whenever someone sinks their teeth into a chunk of food, and that’s before humans themselves are on the menu. It doesn’t take long for even the delicacies on the platform to seem inedible.

In the movie snails are a metaphor for human cruelty and cannibalism.

Generally speaking, though, all the film characters are highly flawed in how they treat animals. They do not view them as sentient beings but instead as nothing more than objects to be used and discarded when they can no longer be used for personal fulfillment or satisfaction. The animal-human relations throughout the movie are quite disturbing and damaging. It illustrates how society, in general, has no respect for the life of an animal. In the Dachshund case, it is not utilized for consumption for most of the film but instead used by its owner, who is herself an inmate, not to lose her sanity. She uses it to keep her humanity, cope with the atrocities committed in prison, and not feel lonely. Once the dog is murdered, she becomes insane and commits suicide. Another purpose of the representation of the animals in the film is for them to be used as symbols or metaphors for something sinister, like the snails symbolizing cannibalism or the other animal products symbolizing prosperity.

The goal of this prison is to teach people solidarity because the table carries enough food for everyone. However, the protagonists discover very early on that the lowest levels often run out of food. At the end of the film, Goreng reaches the lowest level of the pit, where he meets a little girl. While she takes the table to the top as a “message,” the protagonist stays behind. She does not eat the leftovers of the food on the table. The girl could stand for a better future, which can change the system of how humans and animals are treated. For this reason, she goes to the top. The ending is quite hopeful and emphasizes that a change might come. This is completely in contrast to how animals are treated in Chris Noonan’s 1995 comedy-drama Babe, where animals are shown love, understanding, and affection while also being treated with dignity.

Suggestion for Further Readings

Artiquez, Belen, “Animal Holocaust In Film : Researching The Difference In Animal Welfare In Film From 1903 To 2013 With Regard To The Work Of The American Humane Association, Established In 1943”, Esource.Dbs.Ie, 2013 <https://esource.dbs.ie/handle/10788/1224> [Accessed 3 February 2021]

Burt, Jonathan, Animals In Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2004)

Patterson, Charles, Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment Of Animals And The Holocaust, 3rd edn (New York: Lantern Books, 2002)

R. Ascione, Frank, “Enhancing Children’s Attitudes About The Humane Treatment Of Animals: Generalization To Human-Directed Empathy”, Tandfonline.Com, 1992 <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ref/10.2752/089279392787011421?scroll=top> [Accessed 3 February 2021]

Works Cited

Artiquez, Belen, “Animal Holocaust In Film : Researching The Difference In Animal Welfare In Film From 1903 To 2013 With Regard To The Work Of The American Humane Association, Established In 1943”, Esource.Dbs.Ie, 2013 <https://esource.dbs.ie/handle/10788/1224> [Accessed 3 February 2021]

Burt, Jonathan, Animals In Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2004)

Gaztelu-Urrutia, Galder, dir., The Platform(El Hoyo), (Netflix, 2019)

Jones, Sam, “What Netflix’s The Platform Tells Us About Humanity In The Coronavirus Era”, The Guardian, 2020 <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/apr/16/what-netflixs-the-platform-tells-us-about-humanity-in-the-coronavirus-era> [Accessed 3 February 2021]

Noonan, Chris, Babe (Universal Pictures, 1995)

Patterson, Charles, Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment Of Animals And The Holocaust, 3rd edn (New York: Lantern Books, 2002)

Rivera, Alfonso, “Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia • Director Of The Platform”, Cineuropa – The Best Of European Cinema, 2019 <https://cineuropa.org/en/interview/379967> [Accessed 3 February 2021]

R. Ascione, Frank, “Enhancing Children’s Attitudes About The Humane Treatment Of Animals: Generalization To Human-Directed Empathy”, Tandfonline.Com, 1992 <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ref/10.2752/089279392787011421?scroll=top> [Accessed 3 February 2021]