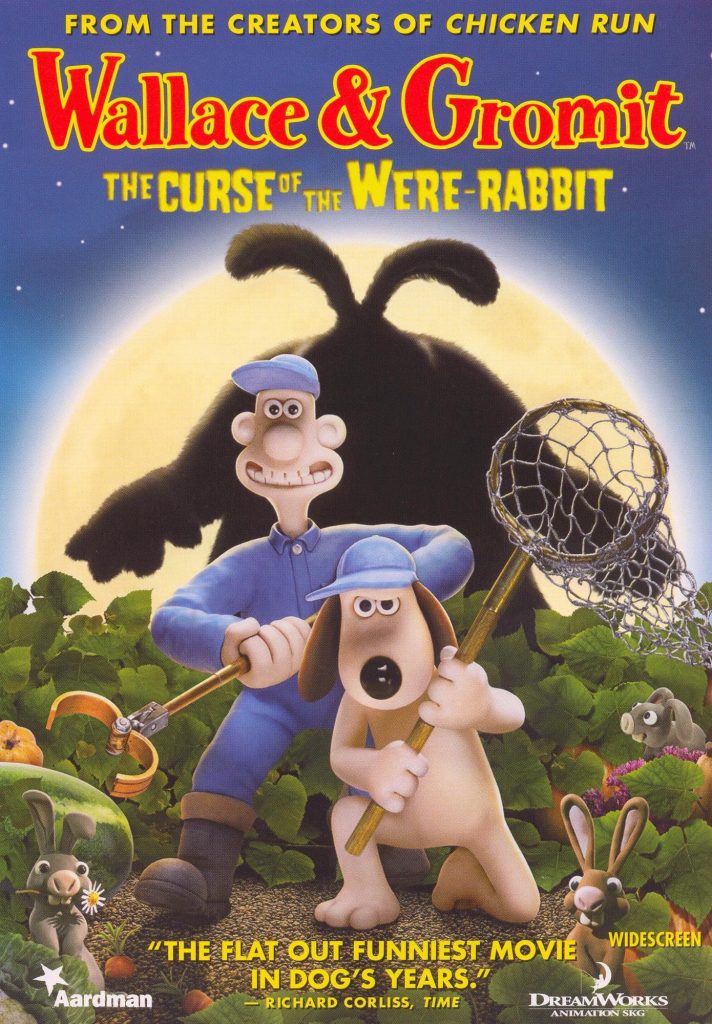

Nick Park’s beloved stop motion clay creations have engaged audiences since 1989, with the unexpected friendship becoming British icons. In 2005 Park introduced a full-length feature movie, Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Wererabbit. Wallace and Gromit star as Anti-Pesto, a dynamic duo ridding their local village of rabbits in preparation for the vegetable competition. The film’s relationship with presenting animals is firmly rooted in anthropomorphism in a unique manner, representing animals to be capable of individual autonomy but not giving them the ability to speak. Gromit is evidence for this, as although he is mute, his emotive facial expressions are recognisably human-like.

Throughout the film, Gromit is given the ability to drive, cook, listen and work machinery, which are uniquely human traits. His mannerisms are distinctly human-like, such as face palming at Wallace’s eccentricity and eye rolling at disasters throughout the film. The audience appreciates that although Wallace seem to be the ‘brains’ and powerful agent in the duo, it is his loyal dog Gromit that is the real mastermind in their friendship. Here anthropomorphism works, as Gromit’s human behaviours and enhanced intelligence allow him to carry out Wallace’s eccentric ideas. The effect of anthropomorphism generates humour and comedy, as Park successfully subverts the human/animal power dynamic. By placing Gromit as the more powerful and intelligent agent within the duo Park promotes animal agency and equality. For example, after Wallace’s disastrous bunny-brainwashing exercise backfires Wallace is transformed into a were-rabbit at the full moon, his innate animalism overpowers his previously human characteristics. Wallace becomes vulnerable and it is up to Gromit to act human in order to save the day.

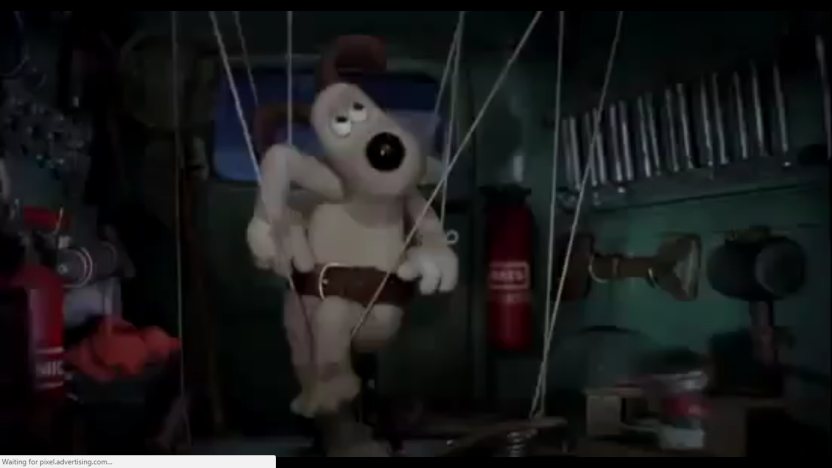

As Wallace and Gromit embark on catching the beast, Gromit is depicted in the back of a van tied to a puppet of a more seductive female rabbit, a scheme devised by Wallace in order to entrap the beast. As Wallace shouts ‘a bit more alluring’ Gromit begins dancing to stereotypical show girl music, kicking his legs in a cancan fashion and winking. Gromit is performing as a female in order to sexually attract a male rabbit, implying that rabbits have the same sexualised inclinations as humans. It also poses the concept that sex is the only way to detract a rabbit from their obsession with vegetables, Park plays on the phrase ‘at it like rabbits’ to decode a rabbit’s innate animalness. Park’s presentation of human and animal sexuality generates subtle comedy suitable for adult audiences, who laugh at the understated reference to sex in children’s animation.

As Wallace disappears the shot focusses on Gromit and his fear in the darkness. Gromit is shown to be sat knitting in the car and listening to the radio, fearfully awaiting Wallace’s return. As Gromit is unable to talk his facial expressions give the audience a clear indication of his emotions, the close-up shots show his eyes widening in fear and then narrowing in determination in order to chase the were rabbit down. This presentation of Gromit is distinctly anthropomorphic; his innate dog-ness is overshadowed by his human-like characteristics. Arguably Gromit’s animalistic traits have transferred to Wallace, who’s were-rabbit persona complies with audience expectations of an innate animal. Park complicates our understanding of human and animal stereotypes by reversing the roles. Each character aligns with the animal/human binary in an unexpected way, generating the humour. The audience reacts to recognisably human traits in Gromit, causing us to respond and align with his character. Contrastingly, Wallace’s transformation has reduced any human traits he possessed, his human personality has succumbed to his beastly alter-ego.