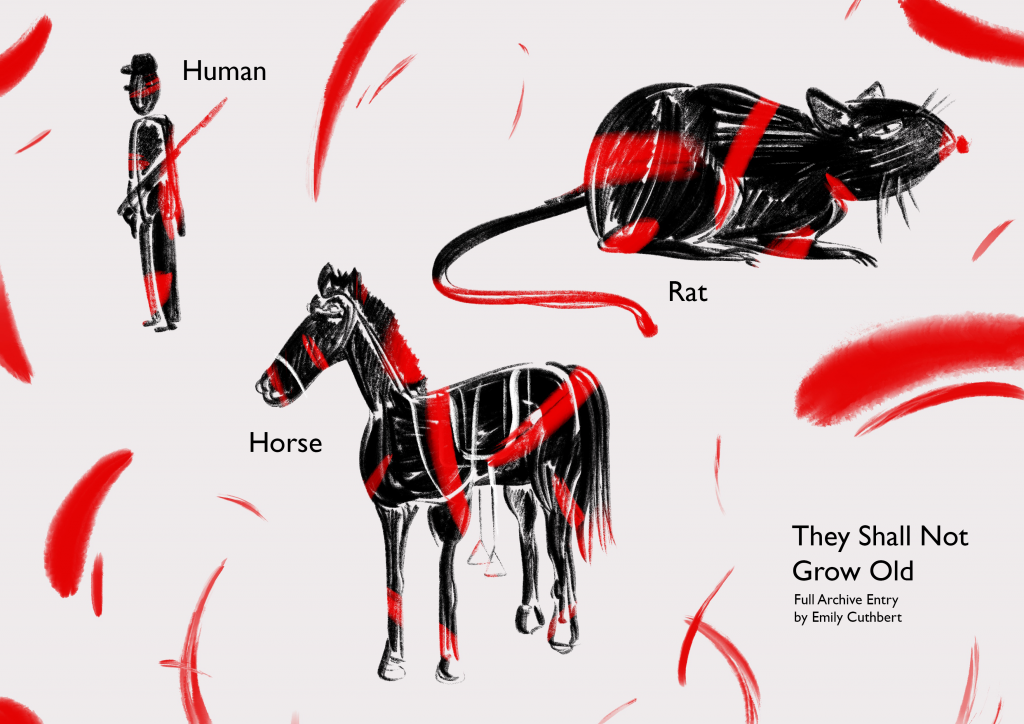

Not often is a film’s purpose so clearly stated in its title, yet Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old1(TSNGO) is a documentary with meticulous dedication to preserving the stories of those who fought in World War One. Framed by black and white footage of pre-war conscription and the return home from combat, the documentary’s centre is filled with painstakingly detailed footage, colourised and restored by hand. The film is narrated by voice-overs from the Imperial War Museum’s archives, whilst the restored film has even been lip-read and then dubbed over by currently serving military personnel. Through the film’s chronological retelling of The Great War, horses come to provide men with companionship and steadiness, whilst rats are viewed with disgust and hostility. The two species produce tremendously different responses, yet both have a commanding and poignant onscreen presence. With their inclusion, Jackson is ensuring that they too, shall not grow old.

The film is a carefully woven together patchwork of footage and interviews chosen by Jackson, which neatly categorises it as an archival documentary. In an interview with The Guardian on why he chose to tell this specific story (Jackson picked from an astonishing 100 hours of footage and 600 hours of interviews), the director responded; ‘There is probably five or six films of this sort that could be made from that archive’2. Jackson’s directorial choices include significant representations of animality; particularly horses and rats. These animals’ representation on film is crucial for the preservation of World War One’s history. TSNGO is dedicated to showing accurate memories of a conflict from which, a hundred years on from 1918, no first-hand witnesses now remain.

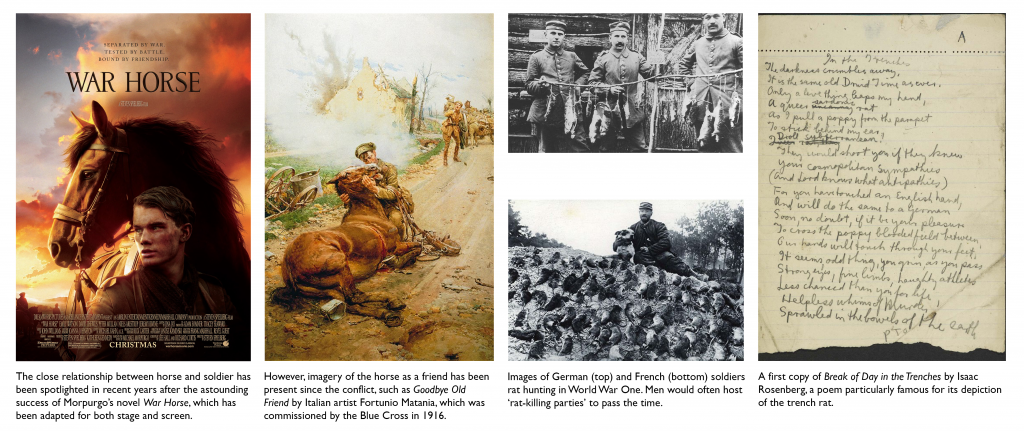

Horses are frequently anthropomorphised, framed as companions in combat – a soldier’s best friend. Jackson’s narrative builds on this history, further reinforcing the message that the soldier and his horse have a unique and personal bond. When a soldier loses his equine companion, the resulting emotions are devastation, grief and heartbreak.

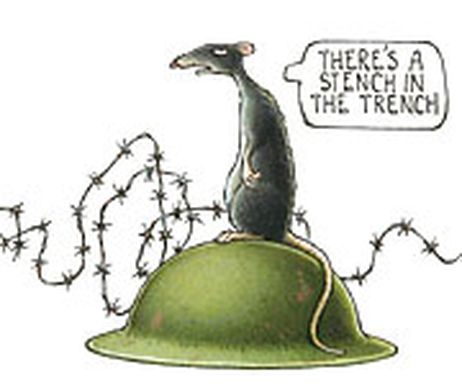

In stark contrast, rats are framed as the enemy of the soldier. In Rat, Jonathan Burt notes that ‘These creatures embody human degradation’3, which is clearly seen in the film’s hostile reception of the species. Their bodies (‘big fat ones’ as one man narrates) become symbols of struggle and violence, as their consumption of flesh transforms them into living reincarnations of the dead for the soldiers.

The difference in reception between horses and rats in TSNGO is clearly signposted by a specific short section in the film, whereby it enters into a direct discourse on soldiers’ encounters with these two species in the trenches.

In his seminal text Why Look at Animals?, John Berger writes that ‘animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange’4. In TSNGO, Jackson conveys this exact opinion in the context of The Great War; horses provide men with a restorative kinship and unbiased gaze. Horses are depicted in unison with humanity, as soldier’s ride atop them, their combined bodies assimilate into the landscape as ‘the cavalry’. From a distance, the two beings merge into one object on-screen, bolstering the union. Jackson shows that this is different to kinship amongst men by the use of wide-angle shots from a great distance. As the viewer is only shown the pairings from afar, the fact that neither horse nor man can linguistically communicate with each other becomes irrelevant. The camera’s physical distance becomes a metaphor for their communicative differences, yet their bodily closeness signifies their compatibility goes beyond language. The long distance shot pans around slightly to view the trauma, producing a POV shot. This in turn distances the audience from the bond, reminding them that the two are of different species, unable to linguistically communicate, yet sharing a unique relationship due to the hellish backdrop of war. One voiceover poignantly notes ‘to lose a horse was like losing a friend’ whilst the sweeping shot of mounted troops being fired at plays. The landscape they ride against is coloured idyllically, with bright blue skies and green grass. This utopian image demonstrates the purity and love with which soldier’s viewed their horses.

Jackson’s choice to contrast the image and narration with each other creates an emotive opposition, which Burt notes the animal image often experiences; ‘This is a tension between their depiction of the ‘authentic’ and the values of feeling and entertainment’5. In TSNGO, this occurs by the gluing of the visual and audible narrative. The audience hears both commentary on the anthropomorphised friendship between man and horse and grizzly descriptions of their deaths. Whilst this takes place, the mise-en-scène focuses on this bond being irreversibly severed by death in a harmonious setting, as explosions and a mix of carcasses litter the screen. However, rather than the separation of authenticity from feeling and entertainment, this juxtaposition places the two together. Jackson pieces together fragments of authenticity, in order to tell an entertaining story about animality.

The director employs the same technique to produce a compelling story about rats. Through his merging together of archival footage, interviews, stills and illustration, the rat too becomes a figure of feeling and entertainment. However, whilst the horse is individualised for entertainment, the is rat objectified.

The film’s direct discussion on the animals is introduced by the transition from a discussion on death; ‘Wherever there was a grave or a body, there were rats’. From this moment, we are aware that the animals are treated as a violent opposition to the horse, their bodies a constant reminder of the deceased. Despite the film’s colourisation, Jackson’s onscreen treatment of the animals is desaturated. In one shot, rats are just made visible by a singular torchlight directed at them whilst they scurry underground. Depictions of living rats are dingy, darkened shots below ground in the trenches, with the only light image of a rat above ground being an illustration. Portrayals of dead rats are distinctly different; shots are lit by daylight and consist of their small carcasses laid atop each other in heaped piles. Jackson makes a distinct point of depicting the rat as a creature that thrives on death and the horrific conditions of the conflict.

Interestingly, rats are also represented as being relentlessly unbiased. In Rat, Burt notes ‘they take no sides and in that sense capture a more general spirit of war.’6. We are aware that rats only arise in the film through a discussion on death, and this small section is the only time they are the central focus of a shot. This is a complete reversal in tone to the sequence of the horse’s death. Instead, we are hearing of the trauma the rats cause (‘the devil scratched my face with the claws of his hind feet’), yet witnessing them thrive. The image of their demise still represents their triumph, as their bodies survive and grow due to the corpses of human and horses. When viewing images of dead rats, Jackson leads us to believe that we may as well be looking at pictures of dead soldiers.

Despite these opposing attitudes to horses and rats, TSNGO adds an additional layer of tension to their animality, as both of their images are romanticised by colourisation. The use of colourised footage breathes a 21stcentury desire for modernisation and empathy with the past into the film. This action confuses the purpose of animal presence, as the restoration of footage capitalises on the relationship between the soldier and animality in order to entertain. The restored image simultaneously pulls itself closer to the reality of the conflict and the perspective of the human eye, yet pushes itself further away from this by deploying the restorative technique to create a performance. From this process comes an equality, as human, horse and rat are given identical treatment.

In the restorative process, film is sped up and frames are blended together. With this transformation the motion of the living becomes smoother and similar to real life motion, yet this highlights the stillness of the deceased. Regardless of species, the motionlessness of the corpse is inescapable in TSNGO. In the trenches, human, horse and rat bodies intermix, and remain voiceless. Archival voiceovers are completely separate from the images projected and were recorded many years after the war ended. As the films were silent, it is only the image of their dead body that was captured. This removes all language from the human corpse, rendering them as voiceless as the animals. Despite the restorative process, no voice can ever be given to the corpses. I am again reminded of Berger’s Why Look At Animals?; ‘Only in death do the two parallel lines converge’7. In death there is no language, and also no ability to have voice. For the first time, human, horse and rat are all equal, and share the same lifeless gaze.

Evidently animality is mandatory when we study men’s experience in the First World War, demonstrated by Jackson’s directorial choices. It is impossible to ignore the polarising impact of horses and rats upon soldiers and the extreme emotions they inspired. After analysing these reactions, it has become apparent that men’s responses to animality are shaped by their removal from society.

The film’s Wizard of Oztransition to colour signifies the relocation away from society. With home a distant space, horses are treated with compassion and intimacy. They become replacements for lost human friendships, families and relationships. Rats replace men’s repressed angst. Particularly in the First World War, soldiers would rarely see the enemy due to spending their life below ground. Rats became the only visual enemy that they would encounter daily. In showing the restorative process onscreen by the shift from black and white to colour, and back again, Jackson exhibits the role that animals played in soldier’s lives by clearly signposting the trenches as a space distant from civilisation. The black and white bookends of the film serve as a reminder of the soldier’s civilian identities where animality is secondary to humanity, whilst the coloured centre creates a microcosm within the film, where humans and animals are equal.

In this central section, Jackson shows that in death, all fades. Horses that were friends and rats that were enemies become equal. Berger’s ‘parallel lines’8cross for a second, and all language is lost, in place of a glossed and unreturnable gaze. The colourisation almost seems a futile addition to the corpse, as the deathly stillness penetrates the image. However, although hard to digest, the inclusion of these images is paramount to the success of the film’s titular objective – to ensure They Shall Not Grow Old.

In showing both the alive animal, and the dead animal, TSNGO comes to illustrate to the viewer that in The Great War, animality came to represent the fleeting nature of life between 1914 and 1918. His rapid-fire selection of shots, one second showing live beings, the next the deceased, remind us that, as Jackson so eloquently puts it; ‘It was a war in full colour if you were a soldier there’9. A war that was inescapably filled with red.

The film’s release date marks the centenary of the end of the conflict, acting as a memorial of the past whilst using the technology of the future. It is a blending of the dramatization of All Quiet on the Western Front and War Horse with the actuality of The Battle of the Somme. In many ways, TSNGOis the culmination of 100 years of filmmaking about The Great War, and with that, animality in war. The two are inextricable bound together.

It is apparent when watching the documentary that by including horses and rats, Jackson places a spotlight upon the extreme opposites in reaction to them over the last century. In doing so the viewer is educated on their significance as a constant outlet in men’s lives in a time when they were hastily conscripted and sent away. It also triumphs in its demonstration of the unique and strange equality humans and animals experienced during The Great War. TSNGO succeeds in its quest to immortalise these important topics regarding animality in the First World War, and performs the critical task of preserving them for present and future generations.

[1] Peter Jackson, They Shall Not Grow Old(United Kingdom: Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., 2018).

[2] Luke Buckmaster, ‘“The Faces Are Unbelievable”: Peter Jackson on They Shall Not Grow Old’, The Guardian(London, 2018).

[3] Jonathan Burt, Rat, 1st edn (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2006), p. 84.

[4] John Berger, ‘Why Look At Animals?’, in About Looking(New York: Pantheon, 1980), pp. 1–28 <http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/gustafson/film 161.f08/readings/berger.animals 2.pdf> [accessed 20 December 2018], p. 6.

[5] Jonathan Burt, ‘Animal Life and Death’, in Animals in Film(London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2002), p. 165-6.

[6] Burt, Rat, p. 84.

[7] Berger, p, 6.

[8] Berger, p, 6.

[9] ‘Peter Jackson: World War One footage brought to life by Lord of the Rings director’, BBC, 2018 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/entertainment-arts-45803977/peter-jackson-world-war-one-footage-brought-to-life-by-lord-of-the-rings-director> [accessed 3 January 2019].

Further Reading & Viewing

Baumel-Schwartz, Judith Tydor, “Beloved Beasts: Reflections on the History and Impact of the British ‘Animals in War’ Memorial.”, History and Memory, 29.1 (2017), 104–133 <www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/histmemo.29.1.0104>

Burt, Jonathan, Rat(London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2006)

Emden, Richard van, Tommy’s Ark (London, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2010)

Jury, W. F., The Battle of the Somme (United Kingdom: British Topical Committee for War Films, 1916)

Milestone, Lewis, All Quiet on the Western Front (USA: Universal Pictures, 1930)

Morpurgo, Michael, War Horse (London, Egmont UK Ltd, 2017)

Spielberg, Stephen, War Horse (USA: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2011)

Bibliography

Berger, John, ‘Why Look At Animals?’, in About Looking(New York: Pantheon, 1980), pp. 1–28 <http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/gustafson/film 161.f08/readings/berger.animals 2.pdf> [accessed 20 December 2018]

Buckmaster, Luke, ‘“The Faces Are Unbelievable”: Peter Jackson on They Shall Not Grow Old’, The Guardian(London, 2018)

Burt, Jonathan, ‘Animal Life and Death’, in Animals in Film(London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2002), pp. 165–98

Burt, Jonathan, Rat(London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2006)

Ioannides, George, ‘Re-Membering Sirius: Animal Death, Rites of Mourning, and the (Material) Cinema of Spectrality’, in Animal Death, ed. by Jay; Johnston and Fiona Probyn-Rapsey (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2013), pp. 103–18 https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1gxxpvf.12 [accessed 20 December 2018]

Jackson, Peter, They Shall Not Grow Old(United Kingdom: Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., 2018)

Johnston, Steven, ‘Animals in War: Commemoration, Patriotism, Death’, Political Research Quarterly, 65 (2012), 359–71 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/41635239> [accessed 20 December 2018]

Walker, Elaine, ‘Into The Valley of Death’, in Horse(London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2008), pp. 118–42

‘WW1 Footage Transformed into Colour’, BBC, 2018 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/entertainment-arts-45803977/peter-jackson-world-war-one-footage-brought-to-life-by-lord-of-the-rings-director> [accessed 3 January 2019]