Hannibal the Animal: An Analysis of Animal Presence in Hannibal

Fig. 1. Hannibal Lecter. All pictures are taken directly from film unless otherwise stated.

The sequel to The Silence of the Lambs, Ridley Scott’s Hannibal is set a decade after FBI Special Agent Clarice Starling (Julienne Moore) closed a serial-murder case with the help of incarcerated cannibal Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins). The case is re-opened when Hannibal’s only surviving victim, Mason Verger (Gary Oldman) – left facially mutilated and paralysed – decides to use Clarice in an attempt to capture his attacker and take revenge. Sure enough, the agent soon receives a haunting letter from her old acquaintance, announcing the end of his cannibalistic retirement in Europe, and thus the hunt begins. Starling mustrestrainChief Inspector Rinaldo Pazzi (Giancarlo Giannini) from meddling with her investigatory work in Italy, whilst defending herself from the corruptive agenda of FBI official Paul Krendler (Ray Liotta), in order to ensure she finds Hannibal before he is captured by Verger and served to his herd of man-eating boars.

As a crime thriller, one can expect a great deal of psychoanalysis permeating the film and its characters. The presentation of animals in the text is hugely important in the exploration of genre; Hannibal is not about animals as cinematic characters, rather the animalistic portrayal of humans. The influence of animal psychology pervades the film, from pigeons to pigs, and it is in this way able to offer an understanding of the complexities of humanity through the use of animals. The ‘thriller’ element of the film is embellished with excessive violence and gore, bordering on horror – a genre obsessed with the animalistic portrayal of the antagonist. Adopting inhuman behaviour and desires, the horror monster, in our case Hannibal the cannibal, is a psychological enigma; they are at once an ‘attractive and mesmerising figure’[1], whilst remaining unacceptable to human society. Hannibal excels by this criterion; his behaviour erratically traverses the human-animal species divide.

The establishment of animal presence within the film arrives with the introductory sequence – a compilation of surveillance footage in a cityscape[2]. The intrusive nature of these shots establishes the theme of voyeurism, both of police authority as well as the unnerving gaze of the unknown. The shots of human activity are sharply cut against footage of pigeons, most notably a writhing mass of the birds pervading the square and the screen. Like rats, pigeons are typically thought of as vermin, congealing around human habitation and thriving from its secretion. The diegetic sound of the birds scratching and beating their wings is amplified by the soundtrack to an uncomfortable level. They are typically associated with uncleanliness and disease, their vast number making them indistinguishable as individuals. It is therefore significant that the footage is intercut with that of human activity, drawing some sort of characteristic duality between the species.

Fig. 2. Hannibal’s image emerges from pigeons in the film’s introductory sequence.

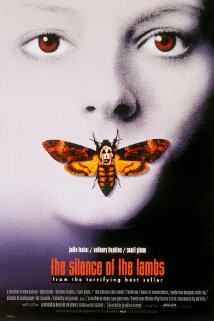

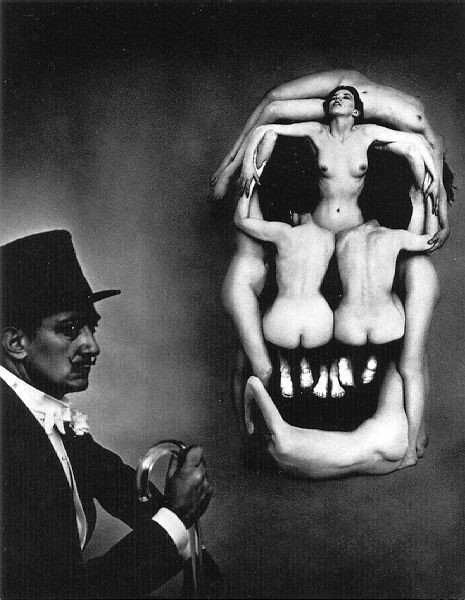

Significantly, the pigeons briefly form the outline of Hannibal’s face at the end of the sequence (00:04:28). This becomes prevalent in the film’s increasing concern with human-animal duality, seen throughout the Hannibal series. The Silence of the Lambs film poster depicts a black and white portrait of Starling (Jodie Forster), her mouth covered by a moth. Known to be a Death Head’s hawk-moth, the pattern on the insects head evokes a skull. It has been widely noted that this image, upon closer inspection, appears to be constructed by the naked female body, emulating vividly Salvador Dali’s ‘In Voluptas Mors’ – a sculpture of five women forming the image of a skull, shot by photographer Phillipe Halsman. Translated roughly as ‘voluptuous death’, the image presents a sinister amalgamation of desire and morbidity, evoking the pleasure of consuming beauty visually, or in Hannibal’s case, physically.

Fig. 3 & 4. The Silence of the Lambs film poster and close-up.

Fig. 5. ‘In Voluptas Mors’, Phillipe Halsman and Salvador Dali (1951) (rebeccambender.wordpress.com).

Hannibal similarly establishes a thematic duality between human and animal. The analogy provided by our cannibal concerning roller pigeons becomes one of the film’s most prominent concepts. These pigeons are known for their inclination to fly high into the air before plummeting to the ground in a backwards rolling motion. ‘Shallow rollers’ Hannibal states (01:31:08), stabilise themselves at a safe distance from the ground, whereas ‘deep rollers’ fall dangerously far before banking last minute. Some deep rollers never manage to bank at all. Clarice Starling, Hannibal concludes, is a deep roller, thus leaving the audience to decipher his meaning. In regards to animal behaviour, there is no clear explanation as to why the birds roll; they do ‘something that is not essential to survive’[3]. Jong Atmosfera indicates the birds seek the sensational effects of the fall, something that can perhaps be read into Clarice’s character. Her commitment to Hannibal’s case goes beyond the call of duty, but ultimately has a destructive risk. In relation to the film, Atmosfera claims the analogy ‘portrays the irregular behaviour of people’, using the phrase ‘naturally foolish’ to define the instinctive desire to behave in a way that is ultimately senseless. To put it frankly, perhaps Clarice persists in the man-hunt because it makes her feel alive.

Fig. 6. Birmingham roller pigeons doing their thing to The Verve (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TO8eLn_h9FQ).

The cross-species embodiment of certain characterisations is most prominent in Hannibal himself. As a cannibal, he is the epitome of the inhuman. He adopts behaviour that is forbidden by the social and cultural laws that human nature is founded upon. He thus becomes the abject of humanity, cast from acceptable normality and deposited against the species boundary. He selects his prey, attacks, and feeds, often eating his victims alive – behaviour associated with wild animals. He is indeed so far removed from humanity that the animal presences within the film appear to acknowledge this distinction. When he enters Krendler’s house, the guard dog, presumably trained to attack intruders, cowers from him. This avoidance occurs again when Hannibal is captured by Verger in an attempt to feed him to a herd of man-eating boars. Bred specifically for the purpose of this execution, the animals, when released, bypass Hannibal completely and instead gorge on Verge’s unfortunate footman. In both instances, the animals are trained to recognise human behaviour, yet fail to identify Hannibal as a target as a result of his inhumanity. Another interpretation is that Hannibal is the apex predator; he is top of the food chain, the alpha, and other animals subsequently avoid him from fear.

Fig. 7. Hannibal, carrying Clarice, make their escape from the man-eating pigs.

Freudian analysis suggests that cannibalism stems from early stages of human identification, in which ‘the object that we long for and prize is assimilated by eating’[4]. The cannibal does not progress through this, maintaining what Freud calls a ‘devouring affection’ for people. These urges derive from primal instinct, along with hunger and libido. Verger reinforces the idea of the Hannibal’s animalistic agenda by questioning whether he wants to ‘fuck [Clarice], kill her or eat her’ (01:22:26), indicating that there is no civilised human motive behind his attraction. He continues to state that ‘to draw him, she needs to be distressed…when the fox hears the rabbit scream he comes a-running, but not to help.’ The primal roles of predator and prey are thus assumed by Hannibal and Clarice Starling (a small tasty bird?), therefore disregarding the animal/human boundary.

The presence of animals in Hannibal directly challenges the concept of human-animal distinction. The film fundamentally rejects a typical biological understanding of the essential nature of the animal; rather than being defined by certain set of non-transferable characteristics, an animal (humans included) adapts and develops its behaviour as environmental circumstances dictate, traversing species boundaries in the process. The film presents this in the human adoption of animalistic behaviour – seen in extended metaphors of pigeons and rabbits, as well as in the smaller details of the film. Clarice analyses the hand-cream absorbed by Hannibal’s letter in order to trace his location; she hunts him by smell, and is subsequently hunted herself as she is stalked through the woods like a deer (01:21:48). The film also reverses human behaviour in direct concern with animals; pigs feast on human flesh, disrupting human cultural contingencies as well as affirming the duality of Hannibal and the animal.

Hannibal and its prequel The Silence of the Lambs both delve into the world of criminal psychology, offering the average viewer a thrilling insight into the twisted minds of those who threaten our happy normality. What is fascinating about the duo is that we meet Hannibal Lecter, not as the horror antagonist and hunted felon, but as a ‘retired’ criminal, working with our protagonist in order to catch the real villain. This approaches the narrative from an unconventional angle, offering the audience a refreshing perspective as well as reflecting the way in which the film challenges the perception of human-animal distinction. Another film which similarly explores the behavioural adaption of a human protagonist is Joe Carnahan’s The Grey, in which John Ottoway (Liam Neeson), stranded in Alaska after a plane-crash, must both psychically and psychologically become the wolf in order to territorially challenge the pack that threaten him. This permeable boundary of animalism is further explored by the character of Hannibal and his fundamental displacement. He clearly exhibits very human qualities; a lover of the classical arts and fine wine, he is fashionable and intellectually charming – overlooking his murderous cannibalism. The film carefully constructs Hannibal to be an unstable embodiment of animalistic conflict, generating a constant sense of unpredictability. This fantastic fusion of the gentleman and the predator is a cinematic reminder to the audience that primal urges forever remain in our instinct; despite our self-endowed superiority as a species, we are ultimately animals, born to kill and eat, and thus be killed and eaten.

I wish you, dear reader, the best of luck in suppressing your inner cannibalism.

Fig. 8. Cheers. (http://etlevinfut.com/vin-et-cinema/)

[1] Barbra Creed, ‘Dining with Dr. Hannibal Lecter’, in Horror and Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Worst Nightmare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 20

[2] ‘Hannibal, dir. by Ridley Scott (MGM, 2001). (00:03:08) All further references given in text.

[3] Jong Atmosfera, Deep Rollers (2009) < https://innerminds.wordpress.com/tag/deep-roller/> [accessed 24 November 2015].

[4] Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1922), in Bartleby, <http://www.bartleby.com/290/7.html> [accessed 24 November 2015].

Biblography:

Atmosfera, John, Deep Rollers (2009) <https://innerminds.wordpress.com/tag/hannibal-lecter/> [accessed 24 November 2015]

Creed, Barbra, ‘Dining with Dr. Hannibal Lecter’, in Horror and Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Worst Nightmare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) pp. 198-202

Freud, Sigmund, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1922), in Bartleby, <http://www.bartleby.com/290/7.html> [accessed 24 November 2015]

Filmography:

‘Hannibal, dir. by Ridley Scott (MGM, 2001)

‘The Grey’, dir. by Joe Carnahan (Open Road Films, 2011)

‘The Silence of the Lambs’, dir. by Jonathan Demme (Orion Pictures, 1991)