Zak Hilditch’s 2017 adaptation of Stephen King’s 1922 follows the story of Wilfred James, a corn farmer living in Nebraska, who, alongside the assistance of his teenage son, Henry, conspired to murder his wife, Arlette, after a dispute about selling her recently inherited land to move to the city. The story unravels the consequences of their actions, and is primarily told through Wilfred’s flashbacks, however, in his retelling of events, Wilfred appears to be heavily distressed by the hallucinations of his victims and his crimes, causing his account to be one-sided which subsequently provides the sense of an unreliable narrator. After his wife’s murder, Wilfred is significantly haunted by his crimes as a result of his growing feelings of guilt, which is portrayed through the presence of rats throughout the film. The rats themselves are symbolic of guilt, and their portrayal is used to comment upon ideas surrounding morality and the egotistical nature of humans,which allows the film to use these animals to encapsulate the journey of Wilfred’s crimes eating away at guilty conscience, ultimately leading to a state of complete insanity.

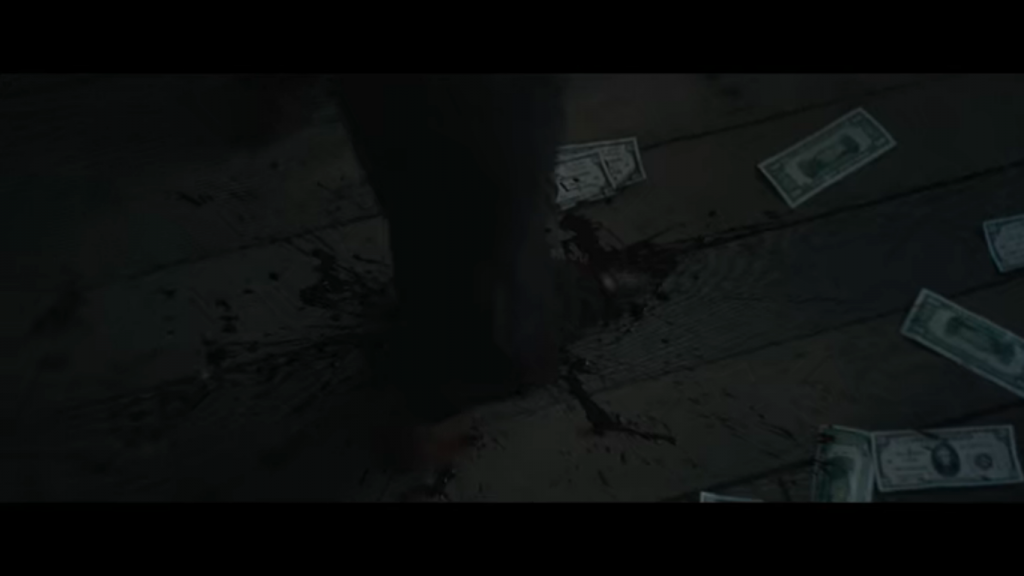

As a psychological thriller, the narrative of 1922 relies heavily upon “the psychological effect that unremitting relentless suspense produces on the audience”[1] that is created in the aftermath of Wilfred’s crimes, through both the growing haunts of the rats as well as his determination to cover up his wife’s murder as a runaway by an unsatisfied wife. 1922 successfully stimulates the mood of the audience by providing high levels of uncertainty and anxiety in the narrative of Wilfred’s insanity, which is represented in the film by the presence of the rats, both in ‘real-life’ and Wilfred’s hallucinations, and the torments they inflict upon Wilfred as a direct result over his growing guilty conscience. These feelings of suspense and the unknown subsequently induce an overwhelming sense of excitement for the audience, which, in turn, acts as a fundamental aspect to the foundations of the film by enabling the narrative to use the role of the rats as a tool to physically thrill the audience, therefore satisfying their cinematic cravings. The film also adheres to the conventions of the ‘psychothriller’ by including a “combination [of elements] borrowed from both horror films […] and from crime films”[2], such as grotesque shots of Arlette’s corpse in Wilfred’s hallucination after her murder (Fig 3), thus allowing the film to encapsulate the ideas surrounding guilt and immoral actions.

Fig 4 shows a rat breaking through the wall.

Fig 5

Rats have made an appearance in many of Stephen King’s novels, allowing this non-human animal to be used as a tool that forces the audience to reflect on the events that occurring and the impact this causes on the characters involved. The significance of the role of the rats is immediately clear from the offset of 1922. The opening scene shows an elderly Wilfred in a hotel room before his attention is drawn to the noises of rats scurrying behind the wall in an attempt to breakthrough. Hilditch’s use of close up shots of both the wall and the fear in Wilfred’s face (Fig 5) to foreshadow the grim reality of the events that we are about to be told in Wilfred’s confession, which in itself is a consequence of the immoral nature of his actions. The state of Wilfred’s mental stability is also made clear from this opening scene; the rats are a hallucination in Wilfred’s mind which is made apparent due to the unrealistic force he has given the rats in his imagination. The small size of these “voracious rodents”[3] makes it unrealistic for the rats to break through the wall by only the force of their own body, suggesting that Wilfred views the rats as a more powerful being than himself due to the torture his hallucinations have inflicted upon him.

The presence of rats in 1922 also highlights the egotistical nature of humans and how they view things as disposable for their benefit, including non-human animals. In an attempt to dispose of his wife’s body, Wilfred throws Arlette’s corpse down the well in his backyard, however, after a few days the body begins to rot (Fig 6). It is in this scene where we are first informed of the presence of the rats within Wilfred’s flashbacks, and how they directly correlate with the murder of his wife as well as his uncontrollable growing guilt. This growth in guilty is portrayed through the handful of rats we see scurrying over Arlette’s body in this scene in comparison to the overpowering numbers that are present in the final moments of the film. The rats that we see surrounding Arlette’s body in this scene are not a hallucination of Wilfred’s mind, subsequently causing the audience to reflect on why rats were specifically chosen as the non-human animal to drive Wilfred to complete insanity.

Within contemporary society, rats are “regarded as dirty, unclean vermin […] typically associated with decay and death”[4] and are present in the more grotesque scenes that occur within films as a result of human stereotypes that are enforced upon the animal. Since rats are viewed to be towards the lower status in the animal rankings and their benefit to humans, it can be argued that this makes them a suitable contender for the source of Wilfred’s insanity. The reality of Wilfred’s crimes places him at the bottom of social rankings due to the selfishness and violent nature of his actions, causing the audience to view Wilfred’s character in the same way they view the rats, therefore, a link can be drawn between the human preconceptions of the worth of rats within society and Wilfred’s new social status, ultimately forcing both animals to be deemed of the lowest status in the society that surrounds them.

Fig 7

Fig 8

Wilfred proceeds to commit his second murder in his attempt to cover the increasing number of rats that are in the well alongside his wife’s body. In this scene, Wilfred and his son, Henry, walk one of their cows on top of the wooden cover of the well (Fig 7) until it eventually breaks, forcing the cow to plummet down and let out a cry of pain before being fatally shot by Wilfred (Fig 8). It is important to note that the cow who now lays at the bottom of the well alongside Arlette is also female, therefore highlighting how animals in the film carry “cultural connotations”[5] by suggesting that the remains at the bottom of the well mirror how women were viewed within society during the early 1920s, and how both human and non-human animal are disposable at a man’s expense. Once the cow has died, all that can be heard in the scene is the scurrying of the rats at the bottom of the well, highlighting the dominance they have in Wilfred’s head. Despite being shot at and having a cow fall upon them, their presence continues to be heard within the scene, therefore highlighting how “Wilfred’s guilt becomes a literal infestation”[6] of rats as the film progresses.

Fig 9

Fig 10

These ideas surrounding the omnipresence of the rats are emphasised in a later scene where we see Wilfred struggling to sleep at night as a result of the dominating feelings of guilt he is experiencing. Before showing visions of large groups of rats that dominate Wilfred’s head (Fig 9), medium shots are used to focus on a hallucination of Arlette’s corpse stood in the doorway of the bedroom (Fig 10). The repetition of the rats’ presence occurring at the same time as the hallucinations of Arlette highlights the inescapable reality of Wilfred’s crimes and how the rats “aren’t just disgusting creatures, but disgusting creatures that reflect on him to his ultimate demise”[7], meaning that the longer he conceals the truth about his immorality, the more the terror of the rats will increase, ultimately highlighting how the rats act as a catalyst for the mental deterioration of Wilfred.

As Wilfred’s hallucinations and mental stability worsen, the film beings to address the contagiousness of immoral actions and the use of animals to “express ideas about human identity”[8] and “human behaviours”[9]. After falling into financial troubles, Wilfred searches his home for money his wife may have hidden from him before her murder. In the scene that shows his endeavour for greater fortune, Wilfred reaches behind a box that is inside the wardrobe in which a rat emerges from behind and bites his hand (Fig 11), putting Wilfred in a remarkable amount of pain due to the infection of the rat’s bite that later causes the amputation of his hand. Wilfred proceeds to retaliate by throwing the rat off his hand and onto the floor before violently murdering the rat by stamping on its’ body (Fig 12). By killing both a rat and a cow, 1922 highlights how within human and non-human animal relations, humans often consider the lives of non-human animals to be less valuable than their own, using them as disposable objects for their benefit with complete disregard towards to consequences that may occur as a result of their actions, thus emphasising ideas surrounding the selfishness of the human ego. Additionally, a sense of irony is created in the aftermath of the rat’s bite in terms of the detrimental impact it had on Wilfred’s health. The size of a rat is incredibly small in comparison to an adult male human, causing the rat to be completely defenceless during the murder yet the aftermath of its’ bite completely debilitates Wilfred.

The final shot of this scene focuses on crumpled up money notes that have been splattered with the rats’ blood (Fig 13), ultimately emphasising the domination of human greed in human and non-human animal relations, and how money, for a human, is regarded to be more valuable than an animal’s life.

The final scene of 1922 shows Wilfred hallucinating once again, however, this time not in flashback form but his hotel room instead, showing the corpses of three people in which his actions have been a contributing factor towards their death: Arlette, his son, Henry, and Henry’s wife, Shannon. During these final moments, Henry holds a knife towards Wilfred, urging him to kill himself whilst rats completely dominate the space in his bedroom (Fig 14). This combination of elements within Wilfred’s hallucination reveals his final state of complete insanity as a result of the dominating presence of the rats, as well as his inability to prevent the consequences that occur as a result of murder. Furthermore, Wilfred’s own hallucinations urging him to commit suicide highlights his desperation to escape not only the terror of his fragmented mental state but also the feelings of “unappeasable guilt”[10] that can never be overcome due to the constant presence of the rats, acting as a reminder of the grim reality of his actions.

Throughout its duration, 1922 adheres to the central theme of murder being “an unforgivable mortal sin that will forever curse its perpetrators”[11] by highlighting the detrimental consequences the act of murder has upon an individual’s guilty conscience, and the domination the feeling of guilt has on everyday life. It is Wilfred’s fragmented mental stability that repeatedly forces him to face the reality of his sinful actions through inescapable hallucinations of the dead and large numbers of rats that dominate his vision, consequently leading him on a downwards spiral to a complete state of insanity.

Rats play a key role throughout the film by symbolising guilt itself, and the way it eats away at Wilfred’s guilty conscience. Despite their lower status within human and non-human animal relations, their actions have a detrimental impact on Wilfred’s quality of life, causing him to have his physical health impacted through the amputation of his hand, as well as having an impact on his mental health by being the direct cause of his final state of insanity. Overall, the rats act as a bridge between the audience and the events that occur within the film by providing an insight into Wilfred’s mental instability and the consequences he is experiencing as a result of his immoral actions.

References

[1] Virginia Luzón Aguado, ‘Film Genre and its Vicissitudes: The Case of the Psychothriller.’ Atlantis, 24.1 (2002), 163–172 (p.165)

[2] Virginia Luzón Aguado, ‘Film Genre and its Vicissitudes: The Case of the Psychothriller.’ Atlantis, 24.1 (2002), 163–172 (p.166)

[3] Leydon, J., ‘Review: Netflix Takes A Stab At Stephen King’, Variety < https://variety.com/2017/film/reviews/1922-review-stephen-king-1202568940/> [Accessed 19 January 2021]

[4] A. Leadbeater, ‘1922’S Ending Explained’, ScreenRant, https://screenrant.com/1922-movie-ending-rats-explained/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]

[5] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2002) p.33

[6] A. Schroeder, ‘Netflix’s ‘1922’ Is A Nebraska Death Trip’, The Daily Dot https://www.dailydot.com/upstream/1922-review-netflix/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]

[7] A. Leadbeater, ‘1922’S Ending Explained’, ScreenRant, https://screenrant.com/1922-movie-ending-rats-explained/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]

[9] M. DeMello, Animals and society: An introduction to human-animal studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012) p.288

[8] M. DeMello, Animals and society: An introduction to human-animal studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012) p.296

[10] Leydon, J., ‘Review: Netflix Takes A Stab At Stephen King’, Variety < https://variety.com/2017/film/reviews/1922-review-stephen-king-1202568940/> [Accessed 19 January 2021]

[11] Leydon, J., ‘Review: Netflix Takes A Stab At Stephen King’, Variety < https://variety.com/2017/film/reviews/1922-review-stephen-king-1202568940/> [Accessed 19 January 2021]

Bibliography

- Aguado, Virginia Luzón, ‘Film Genre and its Vicissitudes: The Case of the Psychothriller.’ Atlantis, 24.1 (2002), 163–172

- Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2002)

- DeMello, M., Animals and society: An introduction to human-animal studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012)

- Hilditch, Zak, dir. 1922 (Netflix: 2017)

- Leadbeater, A., ‘1922’S Ending Explained’, ScreenRant, https://screenrant.com/1922-movie-ending-rats-explained/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]

- Leydon, J., ‘Review: Netflix Takes A Stab At Stephen King’, Variety < https://variety.com/2017/film/reviews/1922-review-stephen-king-1202568940/> [Accessed 19 January 2021]

- Schroeder, A., ‘Netflix’s ‘1922’ Is A Nebraska Death Trip’, The Daily Dot https://www.dailydot.com/upstream/1922-review-netflix/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]

Further Reading

- Caffrey, D., ‘Film Review: 1922’, Consequence of Sound https://consequenceofsound.net/2017/10/film-review-1922/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]

- Vincent, B., ‘Why Did It Have To Be Rats? Bev Vincent Reviews ‘1922’, Cemetery Dance Online https://www.cemeterydance.com/extras/why-did-it-have-to-be-rats-a-review-of-1922-by-bev-vincent/ [Accessed 19 January 2021]