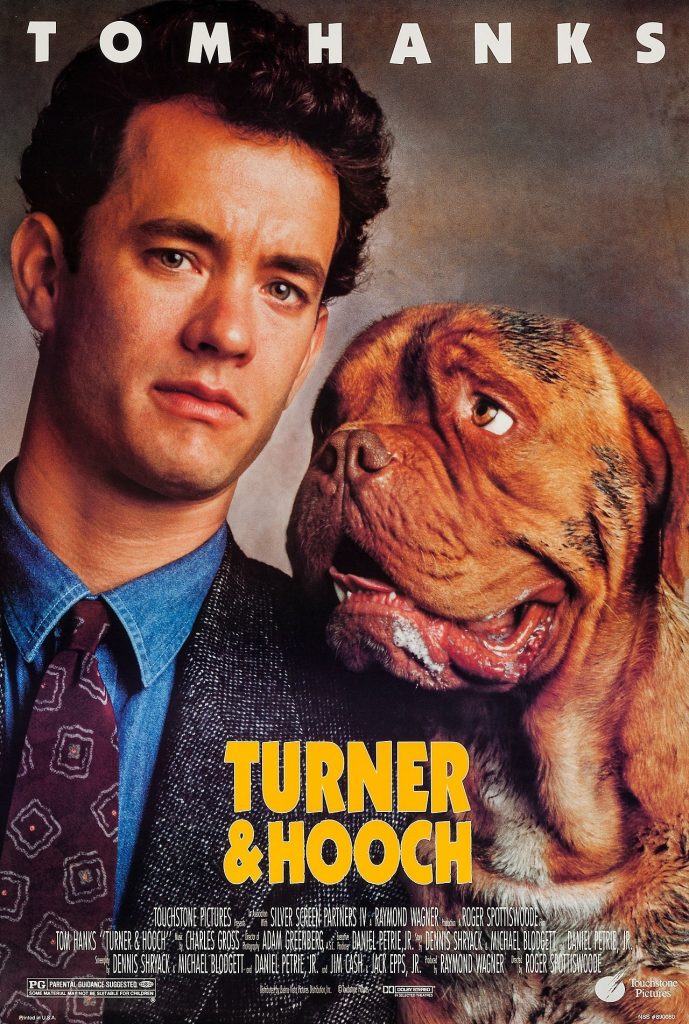

Charles Darwin once stated ‘It is scarcely possible to doubt that the love of man has become instinctive in the dog’. [1] In the case of Turner and Hooch (1989), Hooch’s love for Turner and vice versa takes its time and only arises onside the development of a perfect police office-police dog understanding and partnership. After his previous owner is murdered, Hooch (a Dogue de Bordeaux, described as ‘an immensely powerful mastiff-type guardian’) is taken in by Turner to both prevent him from being euthanized, as well as hoping he will help track down the killer. [2] Fundamental to this comedic buddy-cop dog film is the relationship between police officer Turner and the chaotic Hooch, and the balance between their battle for dominance and a developing friendship. Therefore, this film explores the companionship between man and dog and shows exactly why canines are the perfect police partners and life companions.

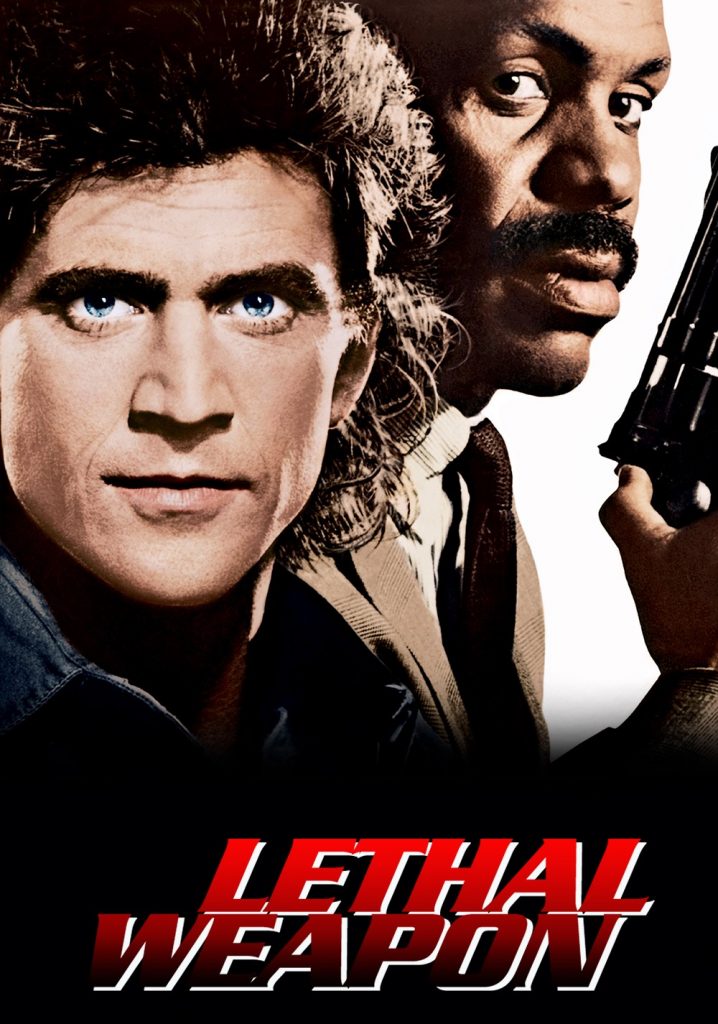

In creating a successful comedy, this film works in the same way as a buddy cop film such as Lethal Weapon (1987) but instead swaps one of the human officers for a canine. Similarly, to Richard Donner’s Lethal Weapon, comedic aspects are created within the plot as the two contrasting personalities of Riggs and Murtaugh clash. Within this film, a sensible police officer, Murtaugh, is forced to partner with the chaotic and complex Riggs. This mismatched duo, like Turner and Hooch, is what creates comedy in the film from their clashing personalities. As the plot thickens, both pairs develop a friendship and become great partners. By portraying one of the officers and main characters as a dog, Turner and Hooch generates a significantly greater emotional connection for the audience. This emotional response is due to humans feeling greater compassion for dogs both on and off the screen. Humans believe dogs lack a certain understanding, much like a child, and therefore feel attached to them as they are seen as innocent and naive. By seeing dogs as loyal companions, but also as animals the audience cannot fully understand, there is a particular emotional connection developed between the audience and Hooch. This is seen as the audience view him much like a child who cannot comprehend what he is doing is wrong. However, this article does further on address the intelligence of Hooch and claim he is to some extent anthropomorphised and therefore just as intelligent (if not more so) as Turner. Hooch and Riggs’s unpredictability and destabilisation of characters’ structured lives are what ultimately create comedy within the films, as well as Turner and Murtaugh’s reactions to this destruction and instability. Lethal Weapon, therefore, works in the same way as Turner and Hooch and demonstrates a relationship turned friendship that is so wrong it is ultimately right!

Turner and Hooch take this mismatched duo and develop the comedy further by having the dominant force of chaos that disrupts Turner’slife be caused by a dog. In both comparison and contrast, Lethal Weapon shows the developing ‘bromance’ created between the two, enabling them to fight the bad guys, whereas Turner and Hooch develop this film (two years on) and create a greater audience emotional response by having one role being a dog. Therefore, the emotional force and deep investment within this film come from a developing friendship between the two and witnessing Turner as he comes to love the dog as the audience does.

Within this film, there is a role reversal of what is usually associated with a human-pet relationship, in which the human has the power over the domestic animal. In this case, an argument can be made in Hooch’s favour where the audience sees complete dominance of the dog as he refuses to let a human control his actions. Consequently, the scene that follows is one in which Hooch’s power over Turner is evident and uncontrollable. In the bath scene, [Fig. 3 and 4], Turner attempts and fails to pull Hooch off of the bed, and then continues to forcefully try and gain the upper hand. Turner is unsuccessful, and the hierarchy which resides with Hooch is demonstrated here. As Hooch is positioned on the bed looking down at Turner, Turner is forced to reach and look up at Hooch. This eye contact between the two shows recognition of one for the other and also an unwillingness of either of them to give up power. In discussing the mutual gaze between animal and human, Jonathan Burt states ‘this exchange of looks is not just a form of psychic connection but also determines the practical interaction that is taking place. In that sense the exchange of the look is, in the absence of the possibility of language, the basis of a social construct’.[3] In this way, this exchange between the two is a mutual understanding between two animals and signifies recognition of both each other and a fight for species dominance. The relationship between the two is therefore already beginning to form, albeit not a positive one, in which there is a recognition of each other. As Hooch looks down on Turner, Turner is positioned below him, in minimal clothing, on all fours. Therefore, it could be argued Hooch’s dominance is seen further through Turner’s animalisation. Turner’s animalisation emphasises Hooch’s dominance and shows a switch of the power dynamic, in which the pet is usually submissive to its owner, and it is the human who towers over the animals. In this feeble attempt of tricking Hooch, it is Hooch who demonstrates intelligence and authority as he outwits Turner, and the ‘battle’ subsequently ends with Hooch over-powering Turner and Turning ending up in the bath he had ready for the dog. Hooch’s dominance within the film is therefore evident and, alongside Turner’s defeated, over-exaggerated reactions, is what creates comedy within the film. The audience, therefore, comes to love Hooch as he creates a heightened sense of joy and amusement, and represents the playful traits dogs have.

An issue raised within this scene, and arguably the entire film, is the question of if sharing spaces with dogs causes issues of species boundaries, considering Hooch here is very clearly shown as the dominant one in the household. Similarly, to us sharing beds and food with dogs, is there arguably a species boundary that is crossed in doing this?… Are dogs our pets or our friends?… Can they be both?… Daniel McCarthy discusses that ‘The notion that dogs exist as reflections of “nature” understate the connections they have with humans, destabilizing many of the inherent anthropomorphic assumptions rooted in biological difference between humans and animals’.[4] In this sense, the species boundaries here are unstable and the animalisation of Turner shows this to illustrate the relationship between men and dogs. However, what is interesting in this scene is when Turner finally does manage to clean Hooch. After tying him up to a fence outside – which we can only assume was a job in itself – Turner ultimately succeeds in bathing Hooch by hosing him down outside. As Hooch barks aggressively, Turner smirks and says ‘This is why man will prevail, and your kind will never dominate the earth. This is what you can do if you’ve got thumbs’. This significant line shows a species hierarchy that unfortunately Hooch cannot escape, despite his evident intelligence. Whilst this clearly shows a significant win for Turner, a certain animalisation of Turner is illustrated as he runs around (almost naked) in his back garden, an unusual thing for humans to do, and body shakes to get rid of water just like Hooch. This bath scene is therefore quite an ambiguous scene and creates comedy in Hooch’s dominance and Turner’s animalisation, but also Turner gaining his dominance back. These significant similarities between the two suggest species categorisations are irrelevant and show equality between humans and animals. Does this equality between the two make you see man and dog as friends, and not master and pet? I think so!

The mutual recognition and equality between the two then develops into companionship and, as a result, Hooch becomes a trustworthy, intelligent police officer and partner. This contrast between Hooch’s defining characteristics of both chaotic and courageous is also what creates the perfect dynamic within the film style of both comedy and audience affection. Within their work relationship, Hooch is seen as what Sanders describes as the ideal patrol dog; ‘intelligent, readily trainable, and physically fit’.[5] As discussed in the bath scene, Hooch lacks the ability to be a properly trained house pet, but comparatively is seen as the perfect police officer by the side of Turner. Therefore, in portraying this police officer-police dog relationship, this film shows the emotional effect and also the safety and importance dogs have on human lives. In one of the final scenes, in which Turner and Hooch track down the murderer – Zack Gregory – Hooch is portrayed as the perfect officer. As Hooch grips Gregory’s throat and growls, Turner interrogates him. Here the audience is shown a popular good cop-bad cop scenario that usually occurs in cop movies. Turner states ‘I can’t stop him from snapping your neck in two’, showing both the authority Hooch has and the undeniable partnership of the two. Linking back to Lethal Weapon, Riggs also chooses a violent approach to battling bad guys in which Murtaugh realises this dangerous characteristic is a useful attribute. As Gregory answers Turner’s questions through blinking, Hooch’s anthropomorphisation is evident as, when he answers incorrectly, Turner states ‘Hooch says you did’. Turner’s trust in Hooch is shown here, as well as an understanding between man and animal through a mutual intuition.

In the next scene, as Turner crouches down next to Hooch outside the warehouse, an evident lack of species hierarchy is represented as Turner lowers himself to Hooch’s level, showing he views him as a friend and partner, not a pet. Turner looks Hooch in the eyes and states ‘Okay, now, Hooch. Is there any way I can get you to understand this? I need you to cover the back. Do you understand? I need you to cover the back’. As Hooch understands and runs off to guard the back entrance, Turner exclaims ‘what a good dog’ showing his acceptance of Hooch as both a pet and partner and the developed love and friendship between the two. In confirming this relationship of dogs as perfect police partners, Devon Thomas and Jenny Vermilya also support this argument by stating that ‘While the actions and attitudes of law enforcement and the criminal justice system communicate a social hierarchy of humans, we argue this same institution applies a similar hierarchy formula to dogs’[6], therefore illustrating the importance dogs have within our society and the power these dogs have if given the status of a K-9 police officer.

It is important to also mention the limitations within this argument. Further research will provide sufficient exemplary representations of other K-9 dogs and their relationships with their handlers, and more evidence can be provided from real companionships, as well as those portrayed in movies. This argument can be further developed through the other human-animal relationships within this movie, for example, Emily and her dog or Hooch’s relationship with Amos before his murder. Through analysing these representations, the emphasis is placed on the companionship between man and dog within this movie. However, this argument analyses Hooch and Turner’s companionship and creates comedy and love within this movie.

Turner and Hooch create an attachment within the audience for Hooch both through comedy, as the audience sees him as a disobedient dog, but also through his courage and faithfulness as a K-9. This film, therefore, presents dogs as both loving family pets and perfect partners. Through movies such as Marley and Me and films that show dogs as secondary characters such as The Other Woman, dogs are painted as loyal and heroic companions, reflective of their owners. However, Turner and Hooch combine these family attributes with dogs seen in films such as K-9 and Top dog, to emphasise the courage and loyalty of dogs. In doing so, this movie presents dog as man’s best friend and protector, illustrating the trust and companionship we place on dogs and the effect they have on our lives. In concluding, this article demonstrates that Turner and Hooch portrays dogs (and arguably all animals) as partners and friends, not pets and inferiors.

Footnotes:

[1] Chares Darwin, The Origin of Species, (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1998), pg. 165.

[2] n/a, ‘Dogue de Bordeaux’, American Kennel Club, < Dogue de Bordeaux Dog Breed Information (akc.org)>, [accessed 08 January 2021].

[3] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), pg. 39.

[4] Daniel McCarthy, ‘Dangerous Dogs, Dangerous Owners and the Waste Management of an “Irredeemable Species”’, Sociology (Oxford), 50.3, (2016), 560-575, (p. 565).

[5] Clinton R. Sanders, ‘” The Dog You Deserve”: Ambivalence in the K-9 Officer/Patrol Dog Relationship’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35.2, (2006), 148-172, (p. 155).

[6] Devon Thacker Thomas, Jenny R. Vermilya, ‘Framing “Friend”: Media Framing of “Man’s Best Friend” and the Pattern of Police Shootings of Dogs’, Social Sciences (Basel), 8.4, (2019), (p. n/a).

Bibliography:

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film, (London: Reaktion Books, 2002).

Darwin, Chares, The Origin of Species, (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited, 1998).

Lethal Weapon. Dir. Richard Donner. Silver Pictures. 1987.

McCarthy, Daniel, ‘Dangerous Dogs, Dangerous Owners and the Waste Management of an “Irredeemable Species”’, Sociology (Oxford), 50.3, (2016), 560-575.

Sanders, Clinton R., ‘” The Dog You Deserve”: Ambivalence in the K-9 Officer/Patrol Dog Relationship’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35.2, (2006), 148-172.

Thacker Thomas, Devon and others, ‘Framing “Friend”: Media Framing of “Man’s Best Friend” and the Pattern of Police Shootings of Dogs’, Social Sciences (Basel), 8.4, (2019).

The Other Woman. Dir Nick Cassavetes. LBI Productions. 2014.

Turner and Hooch. Dir. Roger Spottiswoode. Touchstone Pictures. 1989.

n/a, ‘Dogue de Bordeaux’, American Kennel Club, < Dogue de Bordeaux Dog Breed Information (akc.org)>, [accessed 08 January 2021].

Further Readings:

Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

Charles Darwin, Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

Rebekah Fox, Nancy R. Gee, ‘Great Expectations: Changing Social, Spatial and Emotional Understandings of the Companion Animal-human Relationship’, Social and Cultural Geography, 20.1, (2019), 43-63.

Jamie L. Fratkin, David L. Sinn, Erika A. Patall, Samuel D. Gosling, ‘Personality Consistency in Dogs: A Meta-Analysis’, PLoS ONE, 8.1, (2013).

William F. Handy, Marilyn Harrington, David J. Pittman, ‘The K-9 Corps: The Use of Dogs in Police Work’, Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 52.3, (1961), 328-337.

Reginald Arundel, Police Dogs and their Training

Further Viewings:

K-9. Dir. Rod Daniel. Gordon Company. 1989.

Top Dog. Dir. Aaron Norris. Tanglewood Entertainment Group. 1995.

Marley and Me. Dir David Frankel. Fox 2000 Pictures. 2008.