The Mask[1] is a screwball gangster-comedy starring Jim Carrey as Stanley Ipkiss, a timid bank clerk who finds a Norse mask which turns him into a bold, charismatic and lustful character, much different to his usual self. The portrayal of his pet dog Milo, as well as the cartoon animal characters that share similarities with the mask persona, link together ideas about what it means to be a part of a human-pet relationship, as well as the animalistic behaviours that are demonstrated in mainstream comedy to depict lust and sexual desire.

Milo is Stanley’s pet Jack Russell, and displays typical traits of a loveable, playful dog throughout the entirety of the film. From the very first time we are introduced to Milo, we witness his excitable character: his love of the frisbee and playing with Stanley is what we as an audience would expect from him, and the frisbee grows to be a symbol and reminder of Milo’s behaviour as a dog, despite treated as a human at points within the film. These typical traits that Milo establishes early on are continued throughout the film, and his innate behaviour often gets Stanley into trouble or uncomfortable situations. For example, Stanley finds bags of stolen money that his mask persona has hidden and, in a panic, he throws Milo’s frisbee in the cupboard whilst trying to put the money back.

This irritates Milo, as he can’t understand why his toy has been hidden from him, and he attempts to claw open the door. Any pet in this situation would attempt to get their owners attention as, like Milo, they would be unable to understand why their toy has been shut away from them. Yet in this scene it is made more comical as it is clear that Stanley is in an uncomfortable position, only being made worse by Milo. The images from this scene show the progression of Milo’s impatience and desperation: Milo tries different ways of getting into the cupboard and is eventually carried off the door by Stanley. The quick changes of camera shot between Milo and the conversation Stanley and the police inspector are having heightens the comical nature of the scene: Milo’s unawareness of the trouble that his owner is in makes Stanley uneasy and panicked, and it gives the impression that Milo will become his liability throughout the rest of the film. We can also hear Milo scratching the door through the entirety of the conversation that is going on in the room, emphasising his persistent nature, a trait which, towards the climax of the film, eventually becomes beneficial to Stanley.

This example of Milo’s behaviour and his relationship with Stanley offers an insight into how their relationship will develop later on: traits and behaviours that irritate Stanley soon become aspects of Milo’s character that he is grateful for. When Stanley is trapped in prison, it is Milo’s determined and stubborn nature that helps Stanley escape: Milo’s persistence in trying to climb the wall to reach his owner succeeds in freeing Stanley, yet it is this stubbornness earlier on that irritated and angered Stanley.

This shift in Stanley’s opinion on Milo’s behaviour can also been seen in the climactic scene at the club, in which the mob members attempt to catch the mask as it flies through the sky, yet it is only Milo who has the ability to catch it. This mimics how he catches a frisbee seen earlier on in the film, that Stanley is reluctant and agitated when Milo wants to play. Yet, Milo arguably saves the day again by doing something that he enjoys doing, yet was punished previously for it.

Both these instances display how Milo was able to humiliate the humans around him, even his owner, simply by doing things that dogs usually do. Although he saves Stanley on multiple occasions, we are constantly reminded that he is still a dog, and still has innate abilities and traits.

Despite Milo becoming a figure of heroic rescue, compared to the other characters in the film, he is a dog and therefore has needs and wants to be expected from a typical pet, such as his desire to play fetch and be cared and nurtured for. Yet, he still is capable of saving his owner and expressing emotional intelligence that seems more endearing than that of a typical pet: when Stanley needs him, he is there, and he can be relied on to be both man’s best friend and his saviour.

When Stanley comes home after trying to get into the club and, in turn, is publicly humiliated, or when Stanley has a problem or is in trouble, such as when he tries to hide the money he has stolen from the bank, Milo still wants to play fetch. It is only when Stanley is taken hostage and can no longer look after him and play with him that Milo shows his true dedication and love as a pet and becomes his owner’s rescuer.

Milo’s constant desire to play and have fun can be seen even to the very end of the film, when Tina throws the mask into the river and Milo jumps in to fetch it, thinking it is still a game. Although this constant desire to play fetch adds comedic value to the film, it also reminds us of Milo’s dog instincts and wants, whilst also presenting Stanley as being helpless and somewhat incompetent without the help and assistance of his beloved pet.

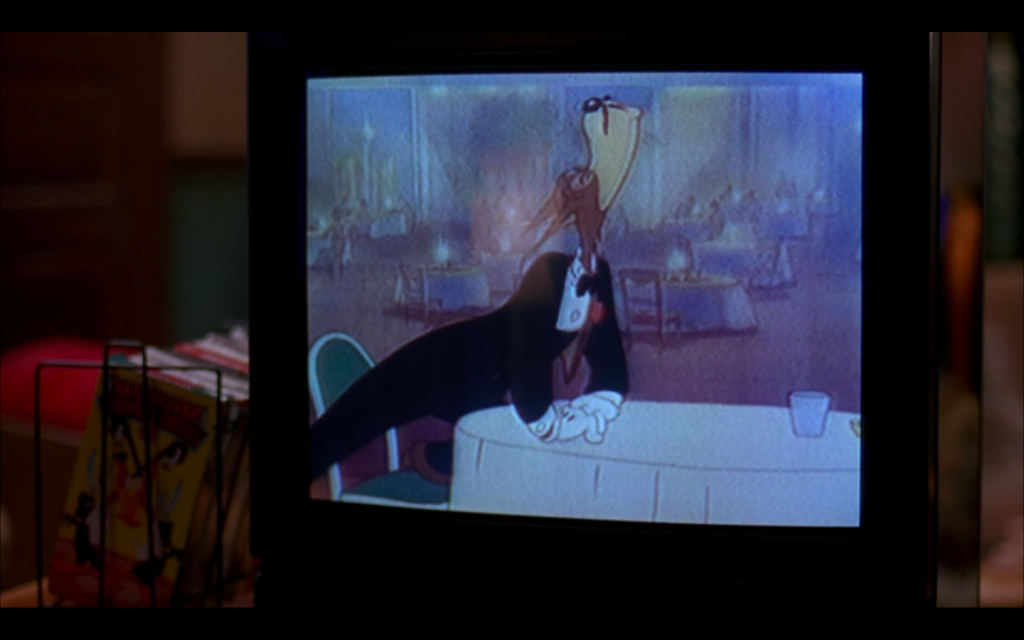

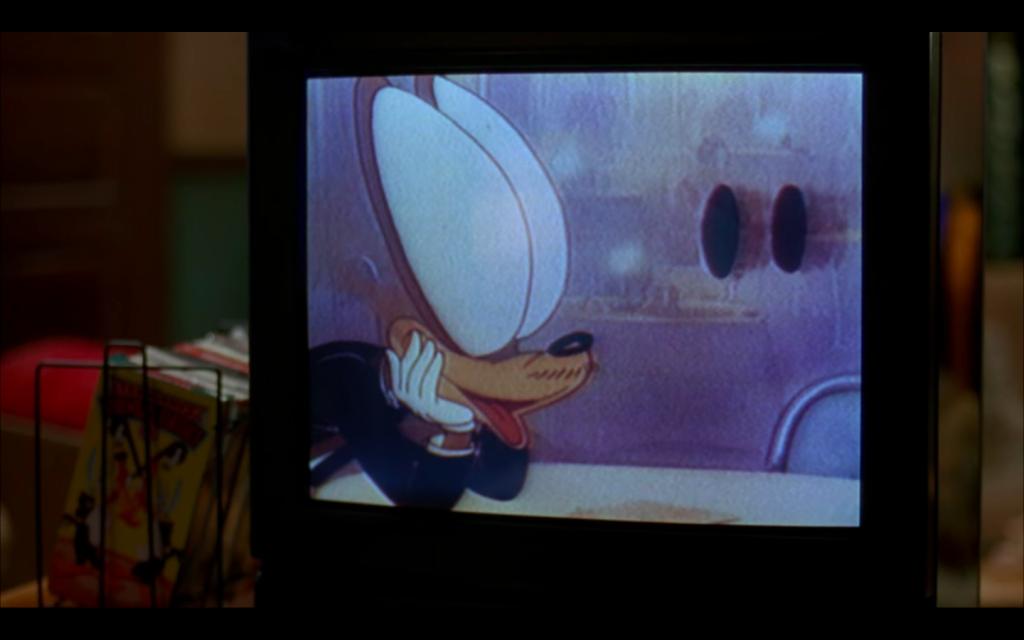

The cartoons that Stanley watches also feature an animal, a wolf, yet the creature is humanised, as he wears clothes and stands like a human. The cartoon shown is by Tex Avery, and was released by Warner Brothers Studio in the mid 1940’s. It is a screwball cartoon in which we see the main character reacting to a woman he finds attractive, making several gestures and sounds commonly used in cartoons to express lust and desire that are almost animalistic in their nature, despite the dog being anthropomorphised. These screwball cartoon character traits can be seen again in Stanley when he turns into The Mask, as he mimics the gestures and sounds that that is made by the cartoon when he witnesses Tina singing in the club, and ultimately becomes a human caricature of his inner self.

The over-the-top reactions imitate the cartoons Stanley enjoys to watch, suggesting that his Mask persona is really a reflection of the kind of person he wishes he was: confident, charming, yet promiscuous and daring. As he watches Tina perform, The Mask turns into a wolf caricature of himself, similar to that seen in the screwball cartoons. This transformation is used to express Stanley’s inner lust and desire for Tina: in the cartoons, Avery depicted these types of animations as a way to express “the sexualised male gaze at women-as-spectacle”[2], and Stanley’s recreation of these lustful expressions makes it clear that he has sexual desires towards Tina.

In Darragh O’Donoghue’s piece on Tex Avery, he also places importance on the phallic imagery that can be seen in the cartoon: “Eyes take on a life of their own, become aggressively phallic, escape their inadequate bodies in order to get a better view, a view craving full possession”. This feature of the cartoon is also replicated by Stanley, as his eyes bulge out of his head, creating a grotesque image of lust, and subjecting Stanley to a state of animalisation. The mimicked behaviour seen from the cartoons depict The Mask character to be sexually motivated, and uses an animalistic libido, comparative to that in the cartoons, to bring a surreal and larger-than-life undertone to The Mask character.

Stanley in his usual form is known for being a ‘nice guy,’ and lacks confidence and a desire to express his sexuality, yet when he puts on the mask, he becomes hypersexual and overly seductive. It is this hyperactive behaviour that mimics the animals in mainstream classic cartoons: as well as Tex Avery’s Screwball Classics, The Mask’s outlandish behaviour harks back to Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and Wile E. Coyote, timeless cartoon animals that are anthropomorphised and display similar slapstick traits that we see from The Mask character. It is this behaviour – the “vulgar caricature and gross exaggeration”[3] of the animalistic nature – that creates the confidence and sexuality that we see from Stanley’s dream self.

Animals in their different forms play various roles throughout the film, impacting on protagonist Stanley’s behaviour and the situations he finds himself in. His pet Milo offers him love and care, although more importantly, he rescues and helps Stanley, to the point in which Milo is really the hero of the film, not Stanley. Yet, the cartoon animals have a greater impact on Stanley’s mask persona: despite the brief shot showing the cartoon of the wolf and the behaviour it displays, those characteristics and gags are repeated and mimicked by Stanley in order to give the mask character a sense of animalistic lust and desire for Tina. Milo is a representation of innocence and the love that is shared in a human-pet relationship, whereas the animated wolf enables Stanley to play out his deepest desires and act with a confidence and seduction that, deep inside, he has always desired to express. The wolf embodies what Stanley is lacking from his life and what he wants to become, whereas Milo represents what Stanley needs and relies on.

References:

[1] The Mask, dir. Charles Russell (New Line Cinema, 1994)

[2] Darragh O’Donoghue, “Tex Avery: Screwball Classics, Volume 1.” Cinéaste (New York, N.Y.), vol. 45, no. 3, 2020, pp. 59. <https://www-proquest-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/docview/2404085850/fulltextPDF/487086A4DBD14973PQ/1?accountid=13828> [Accessed 26th January]

[3] Joe Chidley, “Put on a Happy Face — The Mask Directed by Charles Russell and Starring Jim Carrey.” Maclean’s, vol. 107, no. 32, 1994, p. 54. <http://web.a.ebscohost.com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=70894cd0-c6c5-4533-9e7e-13bb5e4407c1%40sessionmgr4007&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=9408117602&db=buh> [Accessed 27th January]

Bibliography:

Chidley, Joe. “Put on a Happy Face — The Mask Directed by Charles Russell and Starring Jim Carrey.” Maclean’s, vol. 107, no. 32, 1994, p. 54.<http://web.a.ebscohost.com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=70894cd0-c6c5-4533-9e7e-13bb5e4407c1%40sessionmgr4007&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=9408117602&db=buh>

O’Donoghue, Darragh. “Tex Avery: Screwball Classics, Volume 1.” Cinéaste (New York, N.Y.), vol. 45, no. 3, 2020, pp. 58–60.<https://www-proquest-com.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/docview/2404085850/fulltextPDF/487086A4DBD14973PQ/1?accountid=13828>

Russell, Charles, dir.The Mask, New Line Cinema (1994).