Representation of Animals in the Horse Whisperer

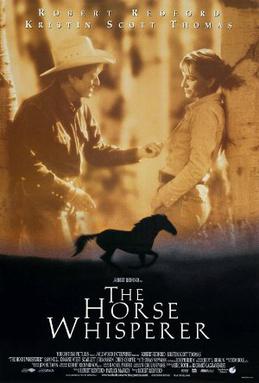

Robert Redford directs and stars in the novel adaptation, The Horse Whisperer (1998). Set between the conflicting environments of urban New York and the rural countryside of Montana, we witness a family fall apart following a tragic accident. Whilst out riding, the film’s young protagonist and her friend come into collision with a truck, which kills Grace’s friend Judith and her horse. Grace survives the tragic accident but both she and her horse Pilgrim are left mentally and physically traumatised. Grace loses her leg, and specialists believe Pilgrim is so badly injured he should be put down. Grace’s mother refuses to give permission to end Pilgrim’s life and instead, determined to reconnect her family, drives to Montana in search of the allusive ‘Horse Whisperer’. As the family move from the chaotic, career driven characteristics of the city, into the sweeping beauty of the countryside, what’s important become apparent. As unexpected relationships blossom, those already existing thrive; as the horse heals, so too does the family.

Despite The Horse Whisperer being set in the American West, the filmredefines the genre of the traditional Western. Commonly associated with ‘ten gallon hats, swinging saloon doors, stagecoaches and showdowns’[1], there are few genres that ‘capture the hearts of their audiences like the Western’[2]. Evidently, The Horse Whisperer succeeds in captivating its audience, yet does not abide by the familiar tropes of the traditional Western to achieve this. In her essay Philosophy of the Western Jennifer L.McMahon states that Western’s ‘explore the nature of human relationships and social organization’. Evidently The Horse Whisperer transcends this Western ideal of the importance of human relations, and instead shifts the focus onto human- animal relationships. Traditionally, Westerns ‘have the tendency to emphasize particular values and exclude, marginalize or misrepresent figures who are nonetheless integral to the history of the American West such as Native Americans… women and animals’[3]. The horse regularly marginalized within the Western, is instead placed in the focus of the action, and given profound significance within a genre within which it was once ignored. The ‘desire to dominate horses that westerns illustrate and promote’ is drastically diminished within The Horse Whisperer, where the plot is driven by the prospect of Pilgrim’s wellbeing and recovery[4]. The conflict often associated within the setting of the Western genre, is instead replaced by the common cause for the horses wellbeing. The Horse Whisperer does still maintain some traditions associated with the Western genre; Barry Langford in his essay: Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond contends that ‘the Western is supremely a genre of exteriors’[5]. Evidently Redford recognises the importance of this generic feature, which is evident in the films use of the beautiful Montana countryside. Gary J Hausladen in his essay Western Places, American Myths argues that ‘the literature of the West is not suited to the novel. It is a genre of visually spectacle’[6]. This is interesting as the film is a novel adaptation, which highlights the fluidity of the genre of the Western, in both literature and film. While still possessing elements of the traditional cowboy as ‘strong in his physical, intellectual, and moral capacities’ and at times is ‘not a man of words, is a man of deeds’, Tom Booker is not a typical ‘stock character’ archetypally found in the Western genre[7]. He is, in fact, an extremely diverse character, who through his appreciation, rather than domination of Pilgrim, is able to re-connect a damaged and broken family, and ultimately save an animal so commonly misused within the Western genre.

The friction between the hectic civilisation of the city and the simplistic tradition of the rural lifestyle is a conflicting theme which threads throughout the film. Interestingly, it is the presence of Pilgrim that brings these two polarised environments together; highlighting the power of animals to defy these conflicting ideals. The fact that an animal, often silenced within the genre in which it is commonly portrayed has the power to bring two opposing environments together sharply undermines the Western which places little significance on the horse. The fact Redford refrains from using such methods as anthropomorphism to portray Pilgrim reinforces the power of the animal in its natural environment. Therefore rather than existing as a mere subplot to the tropes of the Western genre, horses have profound importance within the film. They are symbolic of the conflict between urban and rural life, and embody the fragility of the natural world at the hands of industrialisation. The film begins with the powerful silhouette of a horse galloping across a wide expanse of landscape, whilst the sound of a child laughing can be heard in the background. The freedom the horse evokes becomes synonymous with the notion of childhood innocence. This is reinforced further when Grace wakes and sneaks out of the house; rushing out into the bleak, snowy morning to be reunited with her horse. Here nature becomes a form of escapism from the confinements of urban life, as Grace and Judith find solitude and freedom amongst the vast wilderness.

During this scene, there is an evident parallel, as the camera persistently pans back to scenes of Grace’s mother; Annie jogging through the cemented streets of New York, and working in the suffocating and stressful confinements of the office as editor of a popular magazine. This creates a visual juxtaposition between these polarised environments. Evidently Pilgrim exists in the gulf between these two surroundings; he is most free when surrounded by nature, yet still struggles to escape from the threat of technology and thus the urban influence. This notion is optimised in the brutally visual and tragic scene where the riders and their horses get hit by a truck. The truck is a manifestation of the encroaching threat of urbanisation and technology infiltrating society. By physically knocking down the horses it is symbolic of the city’s threat to nature. As a result of this horrific accident the family escape these confinements, to the sweeping countryside of Montana to the roots of mankind and nature. The Western becomes the embodiment of the idyllic pastoral scene, where the complexities of life are reduced and the importance of nature is revealed.

The animals in the film do not appear as central characters; instead the plot is driven by the human protagonists. However rather than merely existing as an aid to the cowboys in the film like the other horses, Pilgrim is the embodiment of the collision between rural and urban ideals, and stands in the abyss between these two parallels. It is through Pilgrim’s trauma that powerful relationships develop, particularly those between human and animal. The ‘Horse Whisperer’, Tom Booker, is an exceptionally allusive character, who initially appears hostile and unhelpful. In keeping with the Western genre, Booker is portrayed as a ‘lone figure’ that appears ‘estranged from society’. Here the tropes commonly associated with the Western genre are incorporated to develop the plot and further heighten the parallel between rural and urban. Booker’s solitary character stands in stark contrast to Annie, who is symbolic of the east and city lifestyle. She is continuously on her mobile phone to her colleagues back in New York, neglecting her daughter Grace in favour of her career. Interestingly, Annie’s phone rings whilst Tom is training Pilgrim, and it startles the horse quite drastically, resulting in him galloping off into the distance. This is symbolic of Pilgrim’s desperation to escape the associations of city lifestyle to the comfort and solace of nature. As a result of this, Tom spends all day sitting in the field near Pilgrim, until the horse eventually comes to him, which reinforces the strong bond between animal and humans underlying the film. This raw, untainted relationship between cowboy and horse is so rarely conveyed in Western films, where the horses are often simply a prop to aid the action. The power of the bond is reinforced by the frequent close up camera angles which highlight the intimacy between horse and human.

Despite the tragic accident which drives the main plot, there is a strong sense of optimism underlying the film’s intentions. The family leave the entrapment of the city and travel to the rural landscape. Commonly associated with showdowns and violent gun crime, the Western environment, instead becomes a space of escapism and solace for the family and, in turn Pilgrim. As the visual settings change from the suffocating chaos of the city to the freedom and expanse of nature, we witness the power of the natural world to heal. The stark contrast of colour evident in these photos optimises this juxtaposition of environments; moreover the human/animal bond is profoundly more visually obvious once Pilgrim is given the freedom he desires.

It is interesting to note that there are other animals present in the film, yet the focus is solely on Pilgrim’s growth and development. Pilgrim exists between the parallels of urbanisation and industrialisation, so therefore, unlike the rural horses in the film, who are imbedded in that way of life, Pilgrim stands as a stark contrast, as the fusion of rural and urban becomes apparent in his fiery and untameable countenance. Whilst the title of the film places a significant emphasis on Tom Booker’s influence over Pilgrim to heal him, it is in fact the desire to help the animal and the common cause for Pilgrim’s wellbeing in the film which brings the two lovers together, and inevitably the family,. This highlights the underlying power of the horse which has commonly been ostracised and dismissed in previous Western films.

The representation of animals in The Horse Whisperer can be likened to those found in the epic film; War Horse. Similarly to Pilgrim, the horse Joey is a profoundly important character of symbolic meaning; both horses bring characters together and heal them despite the violence which undercuts the films. War Horse begins in the sweeping countryside of Devon, yet abruptly the setting changes to the brutal environment of the War. Similarly to the Horse Whisperer, the film evidently plays around with the parallels between urban and rural; technology and nature. The encroaching influence of machinery and industrialisation is a clear anxiety present in both these films. Similarly to Pilgrim, Joey exists in the gulf between two contradictory ideals; nature and the violent reality of the war and industrialisation. As a result of Joey’s conflicting identity, the protagonists in the film begin to share a kinship through the use of animals in the film, which is a strong message of the power of animals. The titles of both films are interesting to note as they both highlight the importance of the animals in the film, yet place a more weighty emphasis on human influence, through the presence of war and the healing words of Tom Booker.

Further Reading

Brown,J,T.(2004). Deconstructing the Dialectical Tensions in The Horse Whisperer: How Myths Represent Competing Cultural Values. 274

Zamir, N. (1991) War Horse: The North American Review Iowa: University of Northern Iowa 4-8

Bibliography

Hausladen. G, J (2003). Western Places, American Myths: How We Think About the West. Nevada: University of Nevada Press.

McMahon J.L (2010). The philosophy of the Western, . Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. 2.

Langford, B (2005). Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 55.

[1] Langford, B (2005). Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 55.

[2] McMahon J.L (2010). The philosophy of the Western, . Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. 2.

[3] McMahon J.L (2010). The philosophy of the Western, . Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. 7

[4] Ibid, 8

[5] Langford, B (2005). Film Genre: Hollywood and Beyond. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.64

[6] Hausladen. G, J (2003). Western Places, American Myths: How We Think About the West. Nevada: University of Nevada Press. 296.

[7] McMahon J.L (2010). The philosophy of the Western, . Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. 3