Content Warning: This post contains images of a sexual nature including artistic depictions of bestiality.

Park Chanwook’s 2016 erotic thriller The Handmaiden vilifies an octopus as the symbolic ensnarer and physical entangler of the plot and its characters. The complex and intricate plot revolves around Lady Hideko and her handmaiden Sookhee, who fall in love and conspire to free themselves from Hideko’s controlling and exploitative Uncle Kouzuki. The existence of the octopus is constantly implied throughout the film, yet we see little of it: only glimpses behind Kouzuki’s shoulder of a writhing mass of tentacles gruesomely squirming in a large glass container in his basement.

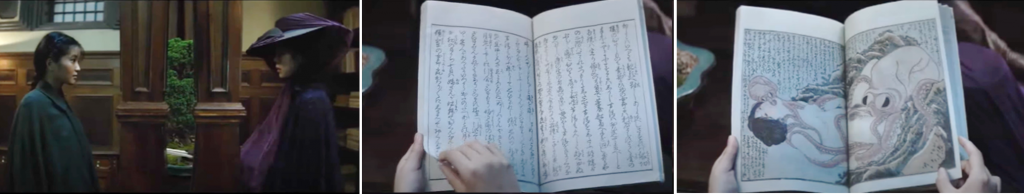

Figures 1-3 – Hideko reveals the art to Sookhee

The octopus’ image becomes a central focus in the emotional climax of the film. The scene consists of Hideko revealing to Sookhee that she has been taught from an early age to read and perform erotic texts to patrons of Kouzuki’s book auctions. Retrieving a book from the shelf and passing it to Sookhee, Hideko crosses a boundary created by a large wooden plinth that splits the screen between the two women. We then move to Sookhee’s point of view, integral to the film’s overall storytelling and particularly impactful here; the camera pans from Hideko’s resigned face to the pages of Japanese verse in Sookhee’s hands. The scene begins with entirely diegetic sound, each rasp of folding paper strikes harshly against the silently mounting tension. Turning the pages reveals to us a shunga artwork of a woman engaged sexually with two cephalopods. The woman and the large octopus share the cramped foreground of the frame as her body and genitals are engulfed in the grasping embrace of tentacles.

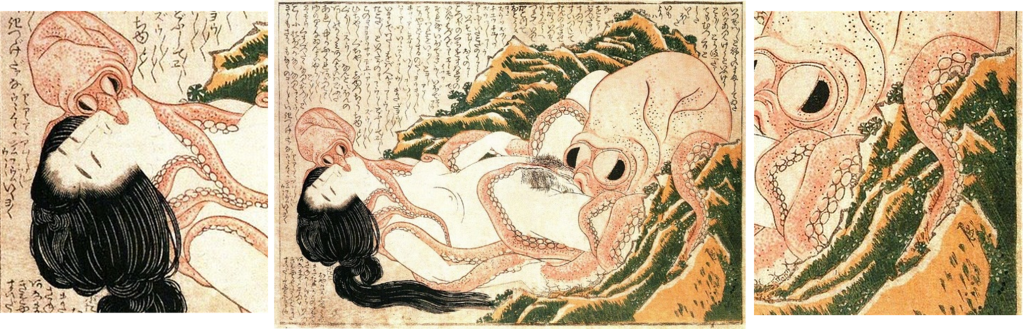

Figures 4-6 – ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ (Hokusai, 1814)

It is significant that Hideko chooses to show Sookhee this particular artwork and not an equally graphic human-centered piece. The artwork itself is ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ (1814) from renowned Japanese artist, Hokusai. Japanese erotic art, or shunga, rose to prominence during the ukiyo-e era of Japanese art and consists mainly of caricature illustrations of comedic sexual scenarios. The works were bought, displayed, and enjoyed by all genders and classes in Japan with the more extreme or absurd pieces often gaining the widest recognition. The inclusion of cross-species encounters in erotica, such as in Hokusai’s print, has therefore garnered a humorous spectacle that is reinterpreted in Park’s film. The whimsical silliness of the original print and its contemporaries has shifted to a more traumatic reality of sinister objectification. This has multiple implications in terms of the film’s themes of cultural contention, sexual indulgence, and the policing of women’s bodies; explicitly placing animals at the centre of this discussion. This representation of bestiality as Hideko’s method of unveiling her abuse epitomizes the interrelation of the film’s sexually explicit scenes, intertwining machinations, and psychological tension.

Figures 5-7 – Depictions of the octopus in Japanese erotic art

Although the octopus is typically deemed to be merely a symbol of Hideko’s exploitation, we must also consider how its image and characteristics have been objectified and fractured throughout the film. We only briefly see its physical existence concealed within the depths of the house, leading our interpretation of the octopus to be drawn only from traumatic flashbacks, Kouzuki’s threats, and the exploitative artwork. With each iteration of the octopus, the animal obtains a calculated depiction as both gruesome and inherently malicious. This is not the first time that Park has included cephalopods in his films. Many viewers of The Handmaiden will be aware of the incredibly horrific scene from Park’s Oldboy (2003) that involves actor Choi Minsik brutally eating a live octopus. This literal consumption of an octopus is carried in spirit to The Handmaiden which consumes the octopus’ image and identity as well as its mantle. Park interweaves allusions to the octopus throughout the film’s imagery from Kouzuki’s ink-stained tongue to the theatrical poster including the tangling of the protagonist’s eight arms.

Figures 8-10 – Octopus allusions in the film and its marketing, and the now infamous scene from Oldboy (2003)

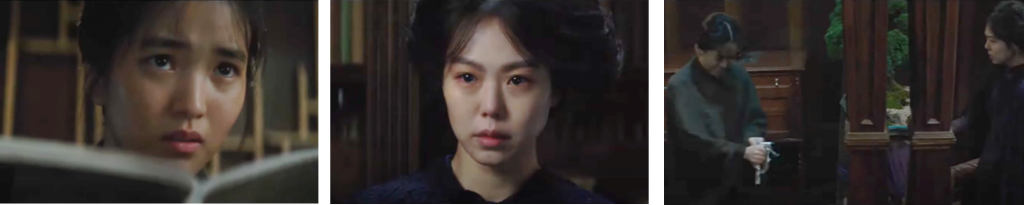

This continual appropriation of the octopus’ image is heightened as Sookhee rips the book from Hideko and begins to tear the pages in wild frustration. A close-up of her frantic hands involves us directly in the destruction of the octopus and the switch to non-diegetic orchestral music sweeps us into the relief of the action. While destroying the print provides catharsis for the protagonists, the physical act of violence solidifies the octopus as a signifier of slimy exploitation. Here Park is establishing conflict between an aged tradition of comical tentacle erotica with our anachronistic disgust towards bestiality and our desire to see Hideko and Sookhee’s liberation. The nature of bestiality is doubly binding for the involved animal who has no agency to resist both the sexual objectification and the consequential fracturing of their identity. By tearing the artwork, Sookhee frees the psychological shackles enforced on Hideko’s sexuality. For the octopus however, its only escape from sexual objectification is its own destruction.

Figures 11-13 – Sookhee destroys the artwork

Park, Chanwook, dir., The Handmaiden (CJ Entertainment, 2016)