In an old house in the midst of the Second World War, entry to the magical world of Narnia is discovered hidden away in a dusty wardrobe behind even dustier coats. Once in this magical land, whose rule by the omniscient lion Aslan has been overthrown, the Pevensie children must help restore Narnia to its former great sovereign by defeating the White Witch and ending the Hundred-Year Winter. Having already crossed a physical boundary in entering this enchanted land, the children must face creatures that transcend the status of animal. With the help of a hilarious pair of beavers, a fox evincing all forms of bravery and an army of centaurs surrendering their life to the cause, the Pevensies lead this animal army to victory, before being crowned kings and queens of this great land. The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, adapted from the first of C. S. Lewis’s novels in The Chronicles of Narnia series, embodies Bouse’s affirmation that one of the most important elements of animals in film is the idea of identification with them as they become ‘idealized embodiments of morally and socially desirable qualities’[1] and this is done through the attribution of what are considered human qualities onto animals.

Ward states that ‘film is a powerful storyteller; employing narrative, visuals, and music enhances its power to communicate a vision of moral living’ [2] and this made TLTWaTW a perfect candidate for Disney’s adaption. The fantasy genre grants animals speech and trees the ability to form an army unquestionably; thus the audience is unsurprised by these fantastical elements. Fowkes suggests that the ‘use or misuse of power is a central theme in a number of fantasy films’[3] and this is true of TLTWaTW – the audience must cross the line that divides human and animal in order to recognise the misuse of power in its land, with the hope they will return with a view that is morally ‘right.’ A genre built on escapism and with an emphasis on happy endings[4] the fantasy genre allows Narnia to expose its moral message, intrinsically through the attribution of human characteristics onto animals. Enticing through strangeness[5] the genre of fantasy grants these creatures the ability to act as humans while appearing as animals, which subsequently engages children with the fantastical elements of the narrative while being exposed to greater questions of morality – Bane argued that ‘Lewis could communicate very subtle shades of human personality without taxing his young audience’s level of comprehension or interest. What better way to show royal majesty and glory then by making Aslan “the King of the Beasts?’[6]

In the fantastical world of Narnia we witness four human children entering a world governed by animals with the purpose of making a positive change for them, and this arguably entertains the idea that it is a reflection of humans going into the animal world and wreaking havoc. TLTWaTW questions what we do with control and power, and as a result poses ecological questions about how we as humans abuse the natural world in which we live. A response to C. S. Lewis’s own personal ideology, as an advocate for the rights of animals he believed that animals do not suffer due to evil choices on their part, though they do suffer due to bad choices on the part of humans.[7] Thus, the actions of human have direct, or indirect, consequences for the animal world.Fantasy provides ‘the opportunity to experience ideas outside of the framework of reason and the boundaries of everyday reality’ and in this heightened world divisions between species become allegorical for our world and the way we act, while accentuating the power of speech and language and what makes us human/animal.

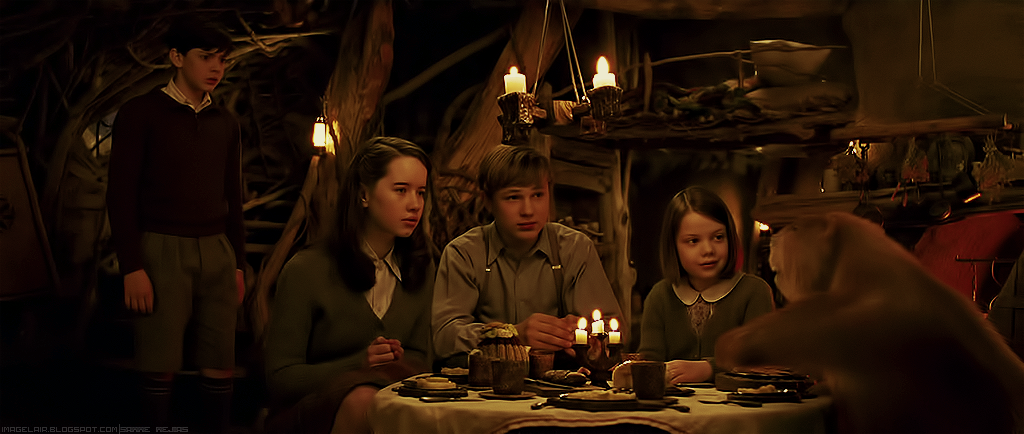

Animal presence can be split into two parts, summarised by Wells who argues that ‘the animal is most noble when nearly ‘human’ while the human is most ignoble when nearly ‘inhuman’’[8] in animation films. This draws on questions of what makes someone human, and is vital in exploring the greater moral message that the film reveals. It is the ‘salt-of-the-earth Cockernee beavers’[9] who look far from human that exhibit the most ‘human’ traits, while the White Witch who appears mostly ‘human’ is defined by her barbarity. Mr and Mrs Beaver are full of compassion and rationale, and comically conform to human gender stereotypes –Mrs Beavers asks the Pevensie’s to “’scuse the mess […] he’s been out with Badger!” This gendered anthropomorphic behaviour plays on the stereotype of a married couple, characterising these animals as ‘human’ through notably signified ways – their compliance to gender stereotypes merely extend from the human world to the animal world, carrying with them the force of humanisation. In the domestic setting in which they prepare fish and chips the framing of these anthropomorphic animals is essential in portraying their equality. When their knowledge is greater than the humans they appear bigger in the frame, almost equal to them, however when they need the power of the Pevensie’s they appear much smaller. This seems to draw on the idea that in the fantasy world of Narnia kinship and equality is not bound among species, and equality is based on the things they do, not the things they are expected do. Beaver mourns the murder of his “best mate” Badger in an incredibly human way; a sombre, melancholic soundtrack plays to denote the effect this has had on him. Similarly, Narnia is also home to Centaurs who condemn betrayal, and a horse who, when told “whoa, horsey!” reprimands Edmund telling him “my name is Phillip.” These human traits being attached to animals extends simple aspects of emotion outwards, treating the animal world as if it were human, while also reducing the complexity of human emotion by presenting the audience with creatures who can also experience emotions we believe to be privileged to majestic world of the humans.

Picture: The ‘Pevensie’s and Mr Beaver’

In contrast, the character whose identification appears as most ‘human’ is the White Witch, yet she rules through barbarity and violence, inverting the typical stereotype of a bestial characteristic by projecting it onto a human form. She wears a fur coat as if to accentuate her contrived bestiality, while her most loyal companions are dwarves – a race of ‘humanoids’ considered as Sons of Earth in the world of Narnia, while also being explicably much more human in appearance than a beaver. Again donned in polar bear fur this implies a cloaking of humanity by animal fur will make them more animalistic, more ‘ignoble’ in terms of Well’s theory. The idea of cloaking is a crucial part of the fantasy genre; the contrast of appearance, which is false, and essence of self, which is true, is key to both the fantasy genre and the moral world of Narnia.

It is the character of Mr Tumnus who bridges the gap between human and animal as his status as a faun – he is neither fully human nor fully animal. A gentle faun with a taste for tea, aesthetically half-animal and half-human, he is the catalyst for the children’s quest, and takes on the role of ‘the (magical) helper’ in accordance to Propp’s character theory. His status as animal then is blurred – he expresses extreme human sentiment in refusing to hand over Lucy to the White Witch once a friendship has been forged between the two of them, arguably siding more with his ‘human’ self than his animal. This is intriguing in regard to Well’s ‘bestial ambivalence’ and the facilitation of animation for cross-species it allows. Well’s draws upon a logic that the animal/human divide and the nature/culture divide have been supposed, and that assumed distinctions between animals and humans means that the line that has been drawn between nature and culture makes them totally separate. Mr Tumnus then rebels against this logic – he has crossed the line between human and animal in order to inhabit two opposite worlds, and seems to inhabit a fantasy land in which this is possible. In accordance to Well’s ‘Bestial Ambivalence Model’ Mr Tumnus could be viewed as the “aspirational human” as he does demonstrate ‘favourable human qualities and heroic motifs’ if we recognise him as an animal – again the blurring of boundaries makes the problematic. Wells draws upon the idea that there is an essential sameness/difference in the divide between nature and culture, and serves as a reminder that while nothing in the fantasy world is fixed, the anthropomorphic capabilities of characters can and will play with expectations. Again, the dichotomy of what is human and what is animal is questioned, challenged, and arguably overturned.

Picture: ‘Lucy and Mr Tumnus’

The implication of this is that one cannot always separate animal and human, and this crossing and blurring of boundaries, from worlds to species, subtly implies that no boundaries are concrete. In Narnia Aslan warns the humans that they must continue to apply the lessons they have learnt in Narnia to their own world – these messages do not only extend through the dusty wardrobe but break the fourth wall and expand into the audiences’ world. These CGI characters exist in the fantasy genre to project this greater message, therefore it doesn’t matter that we don’t all know a family of beavers to pack jam sandwiches as we embark on our next adventure or a fox ready to surrender his life for us, fantasy allows greater moral message to be communicated in an exciting and intriguing way.

While existing on the level of a fantasy film, Lewis’s original narrative was laced with his own personal ideology, and this was something the film could not stray from incorporating. Elemental to the world of Narnia is the biblical model of dominion that Lewis draws on; to have dominion does not grant rights and privileges, but a responsibility to govern well.[10] In Narnia, this holds ecological morals – the responsibility to govern well by protecting the land of Narnia and all who inhabit it. Dominion is held by those in power – here it is the humans, and they must respect this by not misusing the power they have been granted. On the subject of Christianity in his novels Lewis proclaimed that “at first there wasn’t anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord” and it is difficult to watch Narnia without noting the religious allegories that it uses – Aslan is the figure of Christ, represented most obviously through the regeneration scene. As dominion over Narnia is a religious notion, Lewis calls humans to a higher ethical standard in the treatment of creation. Lewis puts the humans of our world and Talking Beasts of Narnia on a higher moral plane than animals (of our world) or dumb beasts (Narnia),[11] and believes that animals possess a conscience, yet on a different level to the one possessed by humans. They hold a different moral compass to humans – we cannot judge an animal for killing another animal in their world, yet as the greater beings we must recognise that we cannot enter their world and abide by their rules – we must act above this. Humans should not act like animals in their treatment of animals.[12] While we can’t look at Narnia and see a truly allegorical representation of a Christian world, Lewis himself wrote that “the Narnian books are not as much allegory as supposal. Suppose there were a Narnian world and it, like ours, needed redemption. What kind of incarnation and Passion might Christ be supposed to undergo there?”[13] thus he is exploring this through the anthropomorphic animals; he does not to need to critique or overly engage in the morals of a human world as it can be explored through the animal world.

This leads on to purpose of the children’s entry into Narnia – the prophecy demands humans for change in Narnia to be brought about, implying that only humans possess enough power to make change. This implication again makes the White Witch a representation of the potential harm this power can do. With this then, the animals in Narnia teach us that our power must come with an awareness of right and wrong. If we as the ‘talking animals’ exploit those considered ‘below’ us we are misusing our power, while presupposing that being in possession of speech comes with responsibility to do so.

Picture: ‘Aslan and Peter’ https://www.moviemuser.co.uk/MovieImages/narnia-lion-witch-wardrobe-slideshow-pic.jpg

What is most important in this however is the idea that responsibility, through dominion, lies at the heart of Narnia, and the anthropomorphic animals symbolise the level of power which is associated with responsibility. In Narnia animals possess a conscience which they express by their complex manner of speech; Aslan grants some of the animals the gift of speech with the expectation that with this comes rationality and responsibility. Aslan rules that if the rational, talking animals are unkind to the mute Dumb Beasts they themselves will become Dumb Beasts also. This degrading of animals by rank for what is considered immoral behaviour projects that there are consequences for possessing these traits, while facilitating the ultimate utopian vision of good triumphing evil. It presupposes that talking animals should behave better than those who do not possess this valued attribute, and thus implies that we, as humans, are the talking animals in our world. The White Witch becomes an example of a human ruling through evil and is an example of unjust power. In a world where status is stratified through the possession of language, Susan’s earlier proclamation that “he [Mr Beaver] shouldn’t be saying anything!” is invalid – fantasy encourages the distribution of traits in any way it pleases, making this disregard of logic a key point to the genre.

In conclusion, The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe is not the only film in the Chronicles of Narnia series which poses such questions of dominion, responsibility and the power of anthropomorphic animals. Prince Caspian (dir. Andrew Adamson, 2008) further develops these ideas, again playing on the expected characteristics of humans and animals and overturning them. The characters of Reepicheep and Nikabrik both disregard logic and refuse to comply to supposed emotions and actions – the former being a mouse who cuts off his own tale in a heroic self-sacrifice to Aslan, the latter a dwarf whose fear of death leads him to betray those closest to him. However, Prince Caspian presents far greater, and more damaging, results of the act of dominion gone wrong – a misuse of power in Narnia means many animals lose their humanlike abilities and return to being Dumb Beasts – possibly a result of exhibiting immoral behaviour. This is presented through Lucy’s encounter with a bear that perceives her as lunch, not a friend or equal.

Other animal fantasy films, take the Ice Age franchise as an example, take a far off setting and use it to promote a moral and right way of living. While Lewis vies for a responsibility over the natural world, Ice Age (dirs. Chris Wedge and Carlos Saldanha, 2002) takes us back millions of years to explore global warming and the effects it can have – a prevalent issue for a twentieth century audience. Similar to the Narnia films, Ice Ages takes advantage of anthropomorphic animals and the power they can represent in animation films to explore such issues, with Roger Ebert arguing that “if kids have been indifferent to global warming up until now, this “Ice Age” sequel will change that forever.”[14] These films then, while having very different plots and production means, use anthropomorphic animals to reveal a greater moral message to the audience, and in particular children, in the hope that they will take from these moral messages and apply them, great and small, to their world.

Picture: ‘Ice Age Movie’ https://ia.media-imdb.com/images/M/MV5BMjEyNzI1ODA0MF5BMl5BanBnXkFtZTYwODIxODY3._V1_SX214_AL_.jpg

Bibliography

Bouse, Derek, Wildlife Films, (Penslyvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000)

Ebert, Robert, ‘Ice Age: The Meltdown’, Robert Eber (2006) <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ice-age-the-meltdown-2006>

Fowkes, Katherine A., The Fantasy Film, (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010)

Freer, Ian, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, Empire Online, <https://www.empireonline.com/reviews/reviewcomplete.asp?DVDID=117198&page=4>, [accessed 19 November 2014]

Higgins, James E., ‘A Letter from C. S. Lewis’ in The Horn Book Magazine, (October, 1966), accessed via <https://archive.hbook.com/magazine/articles/1960s/oct66_higgins.asp>

Walter,James, Fantasy Film: A Critical Introduction, (Oxford: Berg, 2011)

Ward, Annalee R., Mouse Morality: The Rhetoric of Disney Animated Film, (Texas: Texas University Press, 2002)

Wells, Paul The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (London: Rutgers University Press, 2008)

Further Reading

Bane, Mark, Myth Made Truth: The Origins of the Chronicles of Narnia,

<https://cslewis.drzeus.net/papers/originsofnarnia.html> [accessed 20 November 2014]

BBC News, <https://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/5078462.stm> 14 June 2006, [accessed 20 November 2014]

Notes on C. S. Lewis and Animal Advocacy:

BBC, <https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/people/cslewis_1.shtml> 6 August 2009, [accessed 19 November 2014]

Dickerson, Matthew T., and O’Hara, David, Narnia and the Fields of Arbol: The Environmental Vision of C. S. Lewis, (Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009)

MacSwain, Robert and Ward, Michael, eds. The Cambridge Companion to C. S. Lewis, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Pacelle, Wayne C.S. Lewis: Chronicles of Narnia Author andAdvocate for Animals, 12/15/2010 < https://www.huffingtonpost.com/wayne-pacelle/cs-lewis-chronicles-of-na_b_796677.html>

Root, Gerald, Ph.D., C. S. Lewis as an Advocate for Animals, The Humane Society of the United States, < https://www.humanesociety.org/assets/pdfs/faith/cs_lewis_advocate_animals_gerald_root.pdf> [accessed 20 November 2014]

IMDB page:https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0363771/

IMBD page for Ice Age: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0268380/

Trailer for the film:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lWKj41HZBzM

Interesting Newspaper Reviews: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/filmreviews/10535310/The-Chronicles-of-Narnia-The-Lion-the-Witch-and-the-Wardrobe-review.html

[1] Derek Bouse, Wildlife Films, (Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), p. 128.

[2]Annalee R. Ward, Mouse Morality: The Rhetoric of Disney Animated Film, (Texas: Texas University Press, 2002), p. 5.

[3]Katherine A. Fowkes, The Fantasy Film, (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 12.

[4] Fowkes, The Fantasy Film, pg. 6.

[5] James Walter, Fantasy Film: A Critical Introduction, (Oxford: Berg, 2011), pg. 20.

[6] Mark Bane, Myth Made Truth: The Origins of the Chronicles of Narnia, <https://cslewis.drzeus.net/papers/origins-of-chronicles-of-narnia/> [accessed 3 January 2015]

[7] Gerald, Root, Ph.D., C. S. Lewis as an Advocate for Animals, The Humane Society of the United States, < https://www.humanesociety.org/assets/pdfs/faith/cs_lewis_advocate_animals_gerald_root.pdf> [accessed 20 November 2014]

[8] Paul Wells, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons, and Culture (London: Rutgers University Press, 2008), p. 48.

[9]Ian Freer, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, Empire Online, <https://www.empireonline.com/reviews/reviewcomplete.asp?DVDID=117198&page=4>, [accessed 19 November 2014]

[10] Matthew T. Dickerson, and David O’Hara, Narnia and the Fields of Arbol: The Environmental Vision of C. S. Lewis, (Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009) p. unknown.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] James E. Higgins, ‘A Letter from C. S. Lewis’ in The Horn Book Magazine, (October, 1966), accessed via <https://archive.hbook.com/magazine/articles/1960s/oct66_higgins.asp> [accessed 5th January 2015].

[14] Robert Ebert, ‘Ice Age: The Meltdown’, Robert Eber (2006) <https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/ice-age-the-meltdown-2006> [accessed 5 January 2015].