It’s fun to have fun but you have to know how! So, when up-tight, control-freak Sally, and born-to-be-wild child Conrad are left at home for the day, Welch’s reimagining of Seuss’ eponymous, anthropomorphic, wisecracking Cat in the Hat makes it his mission to show them how to enjoy themselves within the bounds of their constraining, oppressive capitalist world that sees both humans and animals as commodities rather than individuals. Accompanied by the animated Fish, Cat and the children go on a mission to retrieve Nevins (the family dog) from the grasp of the film’s villain, Larry, wreaking havoc on the once seemingly “perfect” town of Anville. In this self-reflexive parody of middle-class America, Welch crafts a surrealist world in which Cat constantly blurs the boundaries between realities, forcing the audience to encounter various human-animal relationships, and driving the audience to come to terms with the fickleness of the human exceptionalism paradigm.

Though this may not be the first film that comes to mind when discussing human-animal relations, Cat’s quips about humans’ mistreatment of animals in their capitalist society connects social politics with species politics, making this film an important study in the examination of human-animal relations.

Reimagining its namesake Seuss’ 1957 children’s book (figure 1), the esteemed set designer, Bo Welch, delivers a zany, satirical, carnivalesque, family-friendly comedy that is every snobbish critic’s nightmare in his directorial debut of The Cat in the Hat 2003. Though being incredibly similar to the source material in terms of plot (which is aimed at children of 2-6 years), Welch’s surrealist masterpiece still holds children as its primary audience, catered to through the use of bright colours and dynamic narrative, but manages to keep adults entertained, with hidden, crude innuendos and references to animal pop-culture, in which The Cat in the Hat pushes the boundaries for not only age-rating but also subversive topics regarding animal-human relationships. This film accommodates to all, making it an important film in its study of biocentrism, as its capitalist critique and nuanced views of animal agency are made accessible to all ages.

By mixing the artistic mediums of live action and animation, along with the presence of at least three perspectives (Cat’s, the children’s, and the viewer’s) Welch explicitly raises important issues regarding pet-keeping, stereotyping and the capitalist commodification of animals, ultimately encouraging his viewers to question and even redefine their own human-animal relations, making The Cat in the Hat a threat to the fickle paradigm of human exceptionalism.

“a town that’s not huge, but quite big enough. For buyers and sellers to sell and buy stuff”

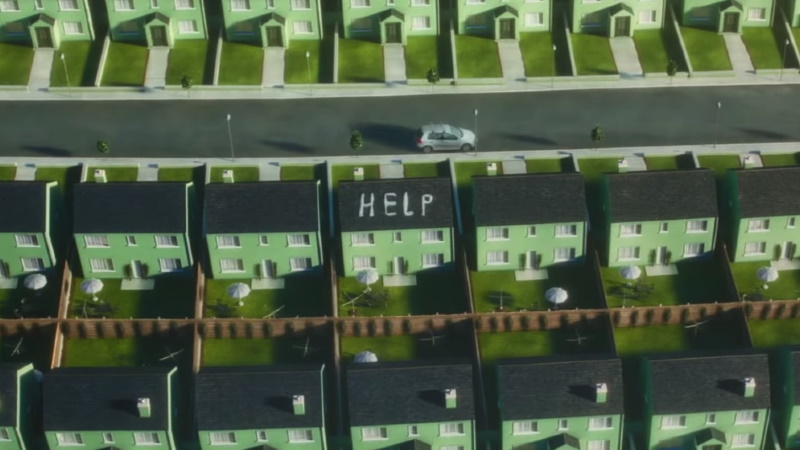

In order to make the audience to understand the necessity of freeing oneself from the deadening nature of capitalism and subsequent commodification of human and animal lives1, McDowell crafts a hellish capitalist suburbia, visually referencing the modern-day middle-class suburbian nightmare (figure 6).

A wide angle shot first introduces the audience to the remarkably constructed dystopia that is Anville (figure 3), showing its isolated nature, already inducing feelings of uneasiness within the audience, readying them for the Cat’s arrival and the realisation of their own toxic human exceptionalism paradigm. The identical, two-toned houses (green and purple – figure 4), are like something out of horror film Vivarium (2019), and the shop signs simply showing the products they sell (figure 5) show the narrow-minded, and capital-and commerce-driven nature of the people that live there. This monotonous setting provides the perfect environment for Cat to infiltrate, and question whether it is possible for human and animals to live harmoniously side-by-side in a world defined by capitalist endeavours.

“I’m a cat that can talk that should be enough for you people!”

Cat’s introduction in the film pays homage to its namesake, Seuss’ text, through the film’s dialogue which reflects the illustrated book exactly, however, using a low angle shot, Welch initially portrays the “humongous Cat” (as Conrad states) in a much more sinister way than Seuss, showing the threat he holds to the anthropocentric mentality that children of their society undoubtedly hold. Despite film Cat’s physical characteristics being very similar to that of the ones Seuss illustrated, he attempts to break out of the boundaries that he was originally written with, “I’m not that good with the rhyming, not really”, showing him in the process of gaining agency by self-identifying his character traits. Despite this he is still shown trying to prove his worth as an individual being to the children stating, “I’m a Cat that can talk that should be enough for you people!”, showing the sad reality of being an animal in an anthropocentric world that in order to be taken seriously non-human animals must do the (usually) impossible.

Cats’ introduction immediately establishes him as the only fourth-wall character, as he exclaims “well that could’ve gone better!” after the children are scared away by him, in a low-angle medium-close up. This proximity unnerves the audience, preparing them for the uncomfortable topics of capitalist conformity and subsequent animal exploitation that follow. But Cat doesn’t only break the fourth wall, he absolutely demolishes it, his interventions showing his absolute removal from the capitalist society the children (and the audience) are a part of and the power he has over the entire film.

As the Cat is introduced to the film after much world building, it is obvious that he is has arrived to disrupt the boundaries of the “peaceful” town that is riddled with capitalist and anthropocentric violence, with his hedonistic philosophy to just “have fun!”.

As he clashes with the social boundaries of Anville, he also clashes with it on a colour theory level. In the “Plan Scene” Cat is shown in close proximity to both the two-toned buildings of Anville and the people within it, all dressed in yellow or green tones (figure 10). The people passing him, stare at him (as you would if you had just walked past a giant talking Cat) but do not react, creating an incredibly Truman Show (1998) atmosphere, showing the deadening nature that capitalism has instilled in Anville’s residents and suggesting that animals are there for the entertainment of humans. The low-angle medium shot makes it feel as if he is addressing the audience, and it is through these particular shots that Welch works to create a sense of familiarity between himself and the audience, subsequently working to debunk the human exceptionalism paradigm.

Cat’s fluid hybrid nature allows him to also take on many human roles within his own, examining first-hand human-animal relations from the side of the humans. He notably presents himself as a mechanic (figure 11), a matador (figure 12), and a hippie activist (figure 13). Looking specifically at the scene where Cat embodies a matador (figure 12), Cat is portrayed in a medium shot in a spotlight as a bull runs towards him from behind. He quickly closes the door just in time, and the bull’s horns pierce through it on either side of him. The spotlight he is placed in references the unfair balance of bulls being placed in the ring for human entertainment, over time wearing the bull down and yet it is the humans who get the glory and the spotlight. The bull’s attempt at getting through the doors of the house reflects the animal’s wanting to break free of the performance sport that humans have undoubtedly forced him to take part in.

By placing this scene in the midst of a diegetic track titled “The Fun Song”, Cat is able to show the cruel juxtaposition between the humans’ callous opinion of what is “fun” and the harsh reality of animal entertainment.

“C’mon kids, you gonna listen to him? He drinks where he pees!”

The fish is the Cat’s opposite, demanding order and unwilling to embrace change. Starting the film as a real goldfish in a bowl, Fish is then transformed into his animated, sentient, and highly-strung self on the arrival of the Cat. Fish works to interrupt Cats grotesque chaos and contradicting his views on anthropocentrism. Being stuck in his restrictive bowl has allowed him to heavily internalise the anthropocentric town of Anville, and the (ironic) fisheye lens and melodramatic music through which Welch depicts him, makes fun of this self-sabotaging internalisation.

Cat plays into this as he works to constantly undermine Fish, reminding the children “he drinks where he pees!” and subsequently of Cat’s own superiority as a ‘sophisticated human/animal hybrid’2. Cat refers to him as “Shamu” referring to the Orca that died as a result of abuse at American entertainment park SeaWorld, showing the catastrophic impacts that human’s commodification of animals for their entertainment.

Furthermore, Fish also works to show the unequal balance of animals in the pet-keeping world, stating that he “Came home in a baggie, loved me for two weeks, and then… NOTHING!” and “A dog goes, “Woof woof,” […] But a fish speaks in plain English…”, establishing the hierarchy of a human world that places more value on some animals than others.

“Nevins, come back!”

Nevins is the only main non-human animal that isn’t present in Seuss’ illustrated text, and it is his addition to the story line that adds to the Fish’s capitalist critique on the effect commodification of non-human animals has on the household pet. He is also the only main non-animal that cannot speak but he still manages to find human-like conscience elsewhere, raising his eyebrows and eating chocolate.

By depicting him as constantly running away, Welch shows Nevins as actively trying to escape the limits that are placed upon him by capitalism. He is literally running away from the anthropocentric ideology that defines him and the humans that dictate his life, even down to his pampering as seen by the bows he wears. Furthermore, as Nevins’ running away is used by Larry in order to get Joan to send Conrad to military school, he represents the multitude of animals (especially household pets) that ‘as nature in general, they are super-exploited and despotically oppressed by the capitalist class’3.

Overall, through the Cat’s obvious crude jokes about the status of animals in society and his plan to get the children to have “Fun!”, the film’s underbelly of the capitalistic commodification of not only animals but also humans is revealed. The Cat’s ability to take on many human-specific roles plays a major part in the exploration of non-human animals’ exploitation for the purpose of human entertainment.

Where Nevins’ character works to show household pets as overly pampered and crafted by humans for humans in the way that they see fit, the Fish represents the “forgotten pet” who has reached its entertainment threshold for the kids, therefore being rendered as “boring”. Welch criticises the human-established hierarchy within the branch of house-hold pets.

Costuming and setting play a massive part in this movie in order to make absurd the capitalist ideology modern-day society relies so heavily on. The neo-1950s temporal setting, gives reference to the time that the original source material is from, whilst also working to show how incredibly backwards ideas of human superiority and exceptionalism are. The cat’s intervention within this world shows the possibility of change in a broken and constraining environment.

Welch’s The Cat in the Hat, is a violently self-destructive satire, forcing all those who watch it to face up to the human exceptionalism paradigm that affects all of us in our society whether we want it to or not, due to the deep-rooted nature of capitalism. It addresses everyone, both adult and children, but not condescending either one, proving to both audiences the importance of dismantling human exceptionalism.

Through the breaking of the 4th wall, the medium-close up through which the Cat is presented in creates a sense of unease, when Cat is trying to get people to think critically for themselves as it discusses humans’ incapability to commit to treating non-human animals with the same respect they have for each other.

This films garish and over-the-top nature works to mask the horrific reality of the position of animals in modern days society as Cat unearths everything about the capitalist structure that plays into the human exceptionalism paradigm and keeps these human-animal hierarchies intact.

This Day has been amazing! Thank you, Cat!

- Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, 1887 < https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-I.pdf> ↩︎

- Kerry M Mallan, ‘The cat’s back! Regenerating subversive humour in The Cat in the Hat’ in Proceedings Children’s publishing between Heritage and Mass Culture, 1-17 (p. 12) <https://eprints.qut.edu.au/4060/1/4060_1.pdf> [accessed 7 January 2024] ↩︎

- Christian Stache, Abstract of ‘Conceptualising animal exploitation in capitalism: Getting terminology straight’, Capital and Class, 44.3 (2020), 401-421 <https://doi-org.sheffield.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/0309816819884697> ↩︎