Bo Welch’s 2003 interpretation of Seuss’ eponymous, anthropomorphic The Cat in the Hat throws the human exceptionalism paradigm into full-blown turmoil as Mike Myers embodies a character that takes on various socially specific, “human” roles all whilst staying in character as Cat.

Though it is not unusual for a film of this genre to depict an animal in disguise, it is unusual for it to use this specific practice to aggressively criticise capitalist conformity. Welch connects the inherent capitalist massification and commodification of non-human animals to the subsequent ethical imbalance of human/animal relations, thus making The Cat in the Hat an eye-opening study into how nonconformity connects social and species politics, a notion exemplified in the “Canine American” scene.

The scene begins with a Dolly-in on the film’s villain, Larry, stopping to frame him in a low angle, medium close-up (figure 1), increasing his perceived height and establishing his (human) superiority complex. The non-diegetic sound that accompanies Larry’s entrance can be likened to the Jaws theme, showing the approaching danger of Larry and the anthropocentric mentality he holds.

A percussion ensemble acts as an auditory cue for audience’s introduction to Cat’s role as hippie activist. Cat is depicted through an eye-level medium shot creating a sense of familiarity that Larry’s framing does not permit. As the scene progresses, however, the initially low angles that Larry occupies become more eye-level as the Cat works to undermine him, showing the shift of hierarchical boundaries between human and non-human, and encouraging the audience to question their own species exceptional discourse.

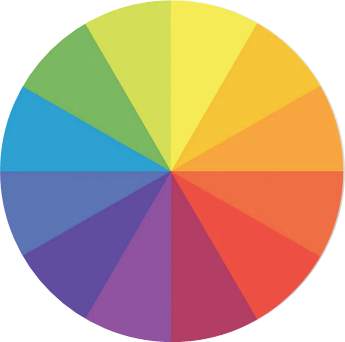

Cat shows an incredibly heightened social consciousness regarding hippie counterculture (so-much-so it could be deemed culturally appropriating was the larger framework of the film not zany and satirical, making fun of everyone and everything) through his dress, politic-stance and even his adoption of the “stoner accent” typically associated with hippicism and characterised by the distinctive vocal shift (“yahhh” instead of “yeah”). Cat’s ability to switch identity crosses the boundary of a fluid autonomy that anthropocentrism labels as strictly “human”. Furthermore, Cat’s dress perfectly encapsulates his own nonconformist, anti-capitalist objectives as, despite wearing the Rastafarian dress associated with Bob Marley and anti-institution hippie culture, Cat does not conform to the colours associated with it (red, yellow, green). He keeps his characteristic red, white, and black, contrasting heavily to the strict yellow, green, and purple colours of Anville’s oppressive milieu (which, thanks to the medium shot, the audience is able to retain a sense of) showing Cat’s unwavering resistance to any type of social structure.

In keeping his distinctive colours Cat controls others’ perception of him subverting ideas that cats are passive creatures and taking charge of the typically branded “human” ability to fluidly self-present. Cat is therefore depicted as an individual attempting to show, like hippie counterculture, that there is possibility for individuality in the rigid, fruitless system of capitalism where non-human animals are seen as a collective entity.

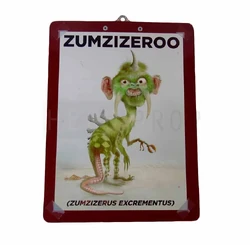

Along with costuming, Cat adopts an animal-rights activist stance holding a petition to save the Zumzizeroo from “senseless wholesale slaughter”. As Larry only signs the petition to “get [Cat] out of [his] face”, the audience is exposed to the sad reality of human indifference to animal cruelty.

Though Cat’s advocacy focuses on the undomesticated Zumzizeroo, the domesticated Nevins can also be seen as having no option but to be a mere instrument in the battle between Larry and children, being passed person to-person rather than having autonomy.

Cat acts affronted when Larry uses the “offensive” “D-word”, stating he would feel more comfortable with the term “canine American”. This technical euphemism pays homage to the myth that cats and dogs are unable to coexist, whilst the playful repurposing of civil rights discourse reinforces the genric conventions of satire, allowing Cat to poke fun at the new “woke” human-saviour tendency to over-categorise. Here, the film works to show that just as it is unhelpful to place dogs within a massified bracket which diminishes the characters of the beings within them (as capitalism endorses), it is unhelpful to over-attribute characteristics, especially for the purpose of social and political agendas, highlighting human’s ability to mindlessly take advantage of non-human animals.

The aggressive anthropomorphism in this scene makes fun of humans’ tendency to place themselves in a position of higher importance than non-human animals. Cat’s ability to change costume blurs the boundaries between non-humans and humans, threatens human exceptionalism and confuses the “standard” distinction between species identity and sentience that human superiority relies so heavily upon.