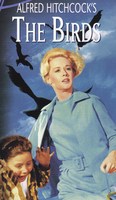

The most horrifying horror of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds occurs in a single, fleeting instant. Thrown from the comfort and security of his own bed, we are allowed only a glimpse of the aftermath of a brutal attack by these inscrutable creatures, where what has happened just moments before is almost too awful to imagine. As the camera jerks forward, we are left with a close-up of the bloodied face of a man with no eyes.

This act of violence remains un-witnessed by us – in the briefest of moments an innocent man has been forcefully reduced to a weak body, left with no agency, where we can only stare into the dark gaping holes of nothingness he has become. The first death as a result of the bird attacks, crucially an attack on the sight, this moment violently re-orientates our own sense of self – our own privileged sense of consciousness as human beings. Freud attributed the loss of eyesight to his own theories on the fear of castration, where the loss of this organ only serves to remind the self of their own inherent lack. Lacan’s theory of the gaze is intimately linked with this – that uncanny moment when we realise the object of our eye is looking back at us, and our own superior sense of self and our surroundings is destabilised. The arbitrary process of assigning meanings, of signification, is realised, and, as in this case, we are left to be defined only by a weak and useless body that bears no privilege to or power over an animal consciousness. We become empty. Our own notions of the rational faculties that orders the world around us and gives us our moral values – that promises us we will be safe and protected within the walls of the home, the walls of linguistic meaning and thought, is violently displaced when the residents of Bodega Bay realise that the birds have a gaze too, and are capable of these seemingly purposeful purposeless attacks. The eye/I is ultimately meaningless, and can be destroyed within a single second of a film’s frame.

The visual excess of the entire film is most poignantly realised in this scene, though crucially the animal agency is not, and does not need to be, overplayed. Its subtlety itself is disorientating for the viewer – whose own privileged cinematic gaze is itself removed by the refusal to show the attack, coupled with the lack of score or other emotional markers at the point of reveal. We are left with just visual, though paradoxically we too become distressingly blind. Everything in the film is reduced to its relation to the senses – to the removal as well as heightening of sensation. Meaning – and with this comes power, violent power – can only be created and maintained through the senses, by embracing this animal shell that hides our nothingness, our lack, and accept the potential force of an animal sexuality that humanity wants to deny in place of seemingly innocent and idyllic country values.

Works Cited

The Birds. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Universal Pictures, 1963.

Lacan, Jacques, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan,

Book XI, trans. by Alan Sheridan, ed. by Jacques-Alain Miller (New York & London: W. W.

Norton & Company, 1981)