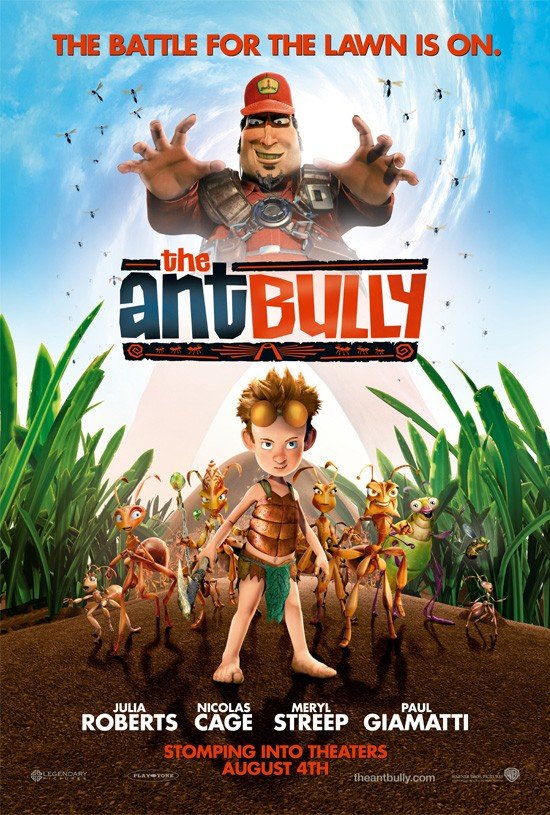

The Ant Bully chronicles the adventure of Lucas Nickle, who demolishes an anthill one day in frustration over being bullied by the neighbourhood kids. In response, the ants shrink Lucas down and sentence him to live and work in the colony as one of their own, with the hope of creating “a brighter future for all ants.” By experiencing the world through an ant’s eyes, Lucas not only gains empathy for those smaller than him, but learns to overcome enemies much greater than him too. The film looks at human-animal relations through the lens of size and power, arguing that an understanding of animals can bring power to a human.

The film is a computer-animated, family-friendly romp, placing it firmly adjacent to Pixar and Dreamworks films of similar theme and tone, blending comedy with fantastical adventure and fable-esque life lessons. More specifically, the film belongs to a trend centred around insects and bugs, which peaked in the 2000s, beginning with Antz and A Bug’s Life, and continuing in 2007 with Bee Movie [2][3][4]. The Ant Bully stands out among the others as being a ‘bug film’ where the main character is a human learning to relate to insects, instead of rarely featuring humans like the former two, or being about an insect learning to live with humans like Bee Movie. Positioning human-animal relations as the arena for an anthropocentric coming-of-age story in this way, the film uses the towering scale of the human world alluded to in its familiars, to put pressure on human views and treatment of animals. Although bug protagonists in other films are anthropomorphised and relatable, Lucas as a human provides a more direct audience surrogate; instead of seeing the film through an ant’s eyes, we see through the eyes of a human seeing through the eyes of an ant, making the human-animal comparison much more apparent.

In the beginning of the film, power and powerlessness are visualised through differences in size. After attacking Lucas, a large bully taunts him with the line “Well, what are you going to do about it, huh? Nothing. Because I’m big, and you’re small.” The link between Lucas’ size and his disempowerment is made clear by this line; he is ‘small’ and therefore cannot, or will not, stand up to his bully. With the words ‘you’re small’ the film presents a medium shot of Lucas, beset on either side by the bully and an anthill.

The bully covers a large portion of the shot, while the anthill is much smaller, and all three subjects are situated next to each other in a horizontal line. By including both humans and animals in this makeshift diagram depicting the relativity of size, and by linking on-screen size difference to implied power difference, the film signals two ideas. Firstly, that the power differences which allow humans to victimise each other also apply to the victimisation of animals by humans; and therefore, that the scale of power which allows for victimisation crosses human-animal boundaries. This sentiment is built on when Lucas attacks the anthill; he repeats the bully’s line word for word. A simple but powerful point is presented; because power scaling crosses human-animal boundaries, a human who is victimised along that scale can in turn pass that victimisation down the chain to animals. One could make the point that the indiscriminate nature of power difference is what allows humans and animals to both be victimised in this way, but the film presents a very different point, as we will see.

The film uses its connection of size and power to illustrate the extent of the power difference between animals and humans. In the next scene, Lucas attacks the anthill, and this is depicted in a way which focuses on the difference in size between Lucas and the ants. The water jets from the toy water gun make high-pitched whizzing noises archetypal of war artillery, as well as being presented through point of view style close-ups, a stylistic flair reminiscent of certain modern war films such as Pearl Harbor [6]. Meanwhile, extreme long shots of the ants escaping from the colony draw focus to the smallness of the ants in the wideness of the destruction, mirroring shots from disaster films such as The Day After Tomorrow, the use of water particularly evoking connotations of flooding and thus natural disaster [7].

By blending war and disaster film tropes together, the film creates a generalised image of the cataclysmic scale on which animals may experience simple acts of victimisation by humans. Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel’s concept of the ‘war against animals’ suggests that it is evident that humans are ‘at war’ with animals owing to the ‘sheer spectrum and magnitude of the legalized lethal violence that humans use against other animals’. In reference to this, Chloë Taylor notes that, ‘we [humans] can easily see ourselves as at war with ‘pests’ such as rats and termites, fighting over the same territories that are our homes’ [8]. Considering these ideas, this scene comments on the nature of animal victimisation by implying that, absent of concerns over territory or utilitarian purposes for killing animals such as pest control, and regardless of societally sanctioned legal animal slaughter, the sheer power humans wield over animals alone is what causes human-animal violence to resemble war. Lucas does not attack the anthill for any reason other than his own victimisation; it is his size, his power, that causes the war-like image. These ideas are cemented when the camera tilts up to give a long shot of Lucas, as the non-diegetic orchestral brass music swells.

A contrast is presented; the mise-en-scène displays a scruffy young boy holding a toy gun, but the upward tilt of the extreme long shot exaggerates his towering size from the perspective of the ants, and the music aggrandises him as a truly fearsome foe. The absurd comedy of this contrast draws emphasis to the idea of human-animal power difference; the tantrum of even a small human child is equal to both war and natural disaster to an entire queendom of animals. In these ways, by tying visual size difference to power difference, the film implies that when human victimisation crosses the human-animal boundary, its effects are magnified to massive proportions because of the relative powerlessness animals experience toward humans. The scale of power which allows animals to be victimised the way humans victimise each other, is also what allows animals to be victimised in ways so disproportionate to humans they resemble an entirely more existential level of human danger. Humans are big, and animals are small.

In light of these ideas, the film articulates an idea of ‘animal power’ through Lucas’ transformation into an ant. Near the end of the film, Lucas takes part in a battle where ants and wasps unite to take down an exterminator, with Lucas himself playing the part of an ant. His ant mentor, Hova, is pinned down by a fallen wasp, and Lucas saves her by lifting it off. Here an echo of the destruction at the beginning of the film is presented; like its predecessor, this moment is also accompanied by the swelling of orchestral brass, but the use of major chords instead of minor fosters a noticeably more positive and heroic sound. This mirrors the music in the earlier scene in a way which specifically signposts transformation; the universal tropes used to describe the two scenes remain in the same realm, but are now being manipulated in the opposite direction, presenting Lucas superficially as hero instead of destroyer.

Lucas is filmed through an upward tilt, and the camera’s position aligns itself with the gaze of an ant once more. Referencing the exaggeration of Lucas’ size from the earlier scene, when considering the ongoing ‘size as power’ metaphor, the repeated angle implies that it is the power itself that is being transformed here. This idea is rounded off through Lucas’ line, “That’s not the way ants are!” meaning that this transformation of power is linked with animality; with ‘being an ant’. In essence, here the film articulates a distinctly coded ‘animal power’, which is separate from the human power of size showcased at the beginning of the film, which a human can tap into by embracing the ‘animal side’.

A look at the mise-en-scène in this moment illuminates the ideas the film associates with animal power; Lucas is not gigantic but small, the wasp is much bigger than him, and his power comes in the form of saving a friend. As such animal power is presented as reversing the established ‘size as power’ motif, and because of the hero-destroyer contrast of this scene with the aforementioned one, the film implies that the transformative nature of animal power can reverse the human-animal relationship of victimisation. Lucas possesses ‘human power’ earlier with his towering size, and later possesses animal power with his small size. Through the small size of animal power the film argues that, if power difference leads to the disproportionate victimisation of animals, the same difference of power implies the disproportionate strength of animals, to push back against such victimisation.

Two central ideas of human-animal relations emerge through The Ant Bully. Firstly, that humans wield overwhelming power over animals. The film displays this by taking intrahuman victimisation, and showing how the power differences which lead to such victimisation apply to human-animal relations as much as they do to humans, if not even more. The visualisation of power difference through size goes a long way to explaining the result of this idea; the film creates a ladder where pain is passed down from humans to animals, showing the gulf of power difference between them. In opposition to this and with the same use of size as a visual cue, animal power is presented as something which pushes back against this dynamic, with the typically moral slant of children’s films, turning Lucas into an animal folk hero. Jonathan Burt argues that, ‘‘Animal agency’ is a phrase that always needs to be qualified by the lack of power animals have in relation to that which humans have over them,’ and this is highly relevant to the topic [10]. The Ant Bully does present animal power as something ‘qualified by’ the otherwise vulnerable position of animals to humans; invariably the ants remain small, but the film argues that animal power is still capable of overcoming ‘human-sized’ destruction, of making a hero out of a tiny ant-boy, and of transforming the destructive power of a human into the heroic power of an animal.

Overall, it is important to consider that The Ant Bully is about transformation. The film’s style and use of images focuses not just on the comparison between, but the movement from big to small; that it showcases human and animal power in this regard is part of explaining how animal power can be adopted or understood by humans. Its viewpoint is distinctly anthropomorphic, not just through the situation of its protagonist as a human, but through its relation to tropes and other films, and that serves to provide an easier foundation for arguing that a human specifically can adopt the ‘being’ of an animal, and become strong like animals are.

Further reading:

Akira Mizuta Lippit, Electric Animal (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000)

Amy Ratelle, Animality in Children’s Literature and Film (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

Dinesh Joel Wadiwel, The War Against Animals (Boston: Brill, 2015)

Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2012)

Notes

[1] Warner Bros., The Ant Bully – Promotional Trailer (2014), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UArmfHdeyk> [accessed 22 January 2021].

[2] Antz, dir. Eric Darnell and Tim Johnson (Dreamworks Pictures, 1998).

[3] A Bug’s Life, dir. John Lasseter (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1999).

[4] Bee Movie, dir. Simon J. Smith and Steve Hickner (Paramount Pictures, 2007).

[5] Honey, I Shrunk The Kids, dir. Joe Johnston (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1989).

[6] Pearl Harbor, dir. Michael Bay (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2001).

[7] The Day After Tomorrow, dir. Roland Emmerich (20th Century Studios, 2004).

[8] Chloë Taylor, ‘Foucault and Critical Animal Studies: Genealogies of Agricultural Power’, Philosophy Compass 8.6 (2013), 539–551, (pp. 540).

[9] Juan Carlos Ulate An ant, or a neuron? (2019), <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/an-ant-colony-has-memories-that-its-individual-members-don-t-have/> [accessed 22 January 2021].

[10] Entomology Today, Ants Can Lift up to 5,000 Times Their own Body Weight (2014), <https://entomologytoday.org/2014/02/11/ants-can-lift-up-to-5000-times-their-own-body-weight-new-study-suggests/> [accessed 22 January 2021].

[11] Jonathan Burt, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2012) p. 31.

Bibliography

Antz, dir. Eric Darnell and Tim Johnson (Dreamworks Pictures, 1998)

A Bug’s Life, dir. John Lasseter (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1999)

Bee Movie, dir. Simon J. Smith and Steve Hickner (Paramount Pictures, 2007)

Burt, Jonathan, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books, 2012)

Carlos Ulate, Juan, An ant, or a neuron? (2019), <https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/an-ant-colony-has-memories-that-its-individual-members-don-t-have/> [accessed 22 January 2021]

Entomology Today, Ants Can Lift up to 5,000 Times Their own Body Weight (2014), <https://entomologytoday.org/2014/02/11/ants-can-lift-up-to-5000-times-their-own-body-weight-new-study-suggests/> [accessed 22 January 2021]

Honey, I Shrunk The Kids, dir. Joe Johnston (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1989)

Pearl Harbor, dir. Michael Bay (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2001)

Taylor, Chloë, ‘Foucault and Critical Animal Studies: Genealogies of Agricultural Power’, Philosophy Compass 8.6 (2013), 539–551

The Day After Tomorrow, dir. Roland Emmerich (20th Century Studios, 2004)

Warner Bros., The Ant Bully – Promotional Trailer (2014), <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UArmfHdeyk> [accessed 22 January 2021]