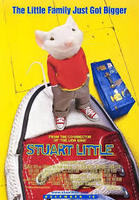

Columbia Pictures’ Stuart Little (1999) follows the Little family’s adoption of an anthropomorphic mouse, Stuart, whose debonair mannerisms and soaring intelligence allow the family to embrace him as an addition to their brood. Whilst Eleanor and Frederick Little’s son George does not conceal his initial doubts regarding the adoption of a rodent, the film presents the notion that the familial bond prevails all, including George’s misgivings; thus, Stuart is soon accepted as a fully-fledged Little. Slower to accept the fact that his stereotypical meal has become hierarchically superior to him is the family’s pet cat Snowbell, who allows his rivalry with our rodent protagonist to create calamity in an attempt to rid his household of his new ‘master’.

The animated family film incorporates elements of adventure and comedy genres to play up to the idea of Stuart as humanlike. Whilst there has been a critical concern that animated animal characters are created “‘hav[ing] a Dell computer chip where their heart should be’”,[1] Stuart engages with humanised emotions and the concept of family to such an extent that he becomes much more loveable than a robotic character. When combined with Stuart’s intelligence, an arguably human quality, it’s the rodent physicality that seems out of place rather than the fact he walks and talks like a young boy. However, there is an overt presentation of binaries throughout the film, with a “construction of the natural world as wild and [a] recognition of culture as a model of apparently civilised social order” used to evoke comedy. Rather than this polarity of the Littles and Stuart “rendering animals and humans as absolutely separate”[2], there is an implication that the family break cultural normality through their adoption of a mouse; yet the fact that the majority of the film’s comedic element derives from them as antithetical entities contradicts this. Stuart Little presents many examples of binaries throughout the film, with a “construction of the natural world as wild and [a] recognition of culture as a model of apparently civilised social order” used to evoke comedy. Rather than this polarity of the Little family and Stuart “rendering animals and humans as absolutely separate”, the Littles attempt to break cultural normality by remaining committed to their adoption of a mouse; yet the fact that the majority of the film’s comedic element derives from them as antithetical entities contradicts this: mainly at Stuart’s expense, for example showing the complication of Stuart brushing his teeth: a task that rodents don’t tend to do.

Despite their eventual bond, George is quick to highlight a number of differences between himself and his new brother in an attempt to support the idea of “animals and humans as absolutely separate” from each other. When the Littles share their first family meal with their new addition, George is encouraged by his parents to interact with his new ‘brother’- yet the only question George can muster up is to “Pass the gravy” (8.36). The mise-en-scene of this scene pokes fun at Stuart’s miniature size, drawing uncomfortably on the disadvantages of being so comparatively small when sat at an overwhelming dinner table next to three (comparatively) gigantic humans. To place Stuart in a shot where he is barely visible against tall chairs and he is served with a plate of the same size that his towering family members is visually hilarious, whilst George’s blunt request merely shatters the mouse’s hopes to establish himself as an equal within the family. The above frame allows the gravy boat, symbolic of domestication, to dominate the shot; visually suggesting that humanity and everything associated with it will remain dominant over animals, and by extension, Stuart. His size is continually presented as his downfall, with Stuart breaking a boat remote control almost shattering his bond with George once again.

As Stuart panders to many aspects of humanisation, it is acceptable for the Littles to acknowledge him as an equal within their family, whereas Snowbell the cat acts purely as a cat and therefore is denounced purely as a family pet. For example, whilst the mouse interacts with his parents verbally, Snowbell mutes himself around humans; allowing the Littles to assume that he is simply a cat, rather than an anthropomorphised animal. Additionally, upon his adoption, a priority for Stuart’s new parents is to provide him with suitable clothing, taking the mouse to a toyshop and choosing clothes from a toy doll, merchandised as ‘Ben’, to dress him in. The novelty costumes presented cause Eleanor Little some concern, hoping to provide Stuart with standardised menswear, rather than the caricatures offered by this superhuman motif. Asking for something suitable for a “simple family party” (16.22) prompts the purchase of a bourgeois toy suit for the rodent, juxtaposing the connotations of “simple”. This antithesis implies that the adoption of Stuart is acceptable because of the family he is entering; a middle-class, nuclear family who have perhaps seen a novelty value in the concept of a rodent son, rather than a genuine attempt to break cultural prejudices. Moreover, whilst Stuart dresses like a human, Snowbell is left unclothed which exaggerates the separation between him and Stuart further, complicating the hierarchy between animals by suggesting that different kind of animals are more humanlike and thus higher up the ‘hierarchy’ than stereotypical animal creatures.

Stuart, Snowbell and Monty hierarchy scene:

The notion that some animated “film programs [are] devoted to the life story of one particular animal” is ostensibly supported throughout Stuart Little, with the eponymous mouse adopting the role of both our hero and protagonist, arguably leaving minimum room for Snowbell’s own narrative development. However, the portrayal of the Persian cat depicts him as one of the film’s antagonists, with him being presented to be isolated from the family he is housed by following the arrival of Stuart. A prime example of this occurs when the Little parents, George and Stuart share an intimate moment and decreeing that they are “the whole family” (32.16). The shot then pans out and shows Snowbell isolated from them on the staircase, a recurring shot that continually reinforces the idea of him as a separate entity from the Little family. Whilst the narrative arc implies that it is the sociological assumption that a cat cannot be inferior to a rodent that prompts Snowbell to seek assistance from the ‘alley cats’ in attempt to rid his territory of Stuart, arguably the actual cause is an emotional longing for acceptance and recognition from the Littles. In many ways, it could be contended that whilst Stuart is more dominant throughout the narrative, most of the film’s climaxes rest on Snowbell’s character and his development with him being responsible for both jeopardising and later securing the mouse’s safety. Thus, it may be considered that that Stuart Little’s narrative is partly “devoted” to Snowbell’s character development, and in turn, his “life story”.

The argument that there’s a great amount of stigma throughout Stuart Little to the notion of adopting an animal as a child is difficult to deflate. Whilst Eleanor and Frederick barely hesitate in ‘choosing’ Stuart, indicating to an underlying sense of commodity as demonstrated through their statement that they’re “leaning towards a boy”, Snowbell, George and many other human characters are initially confused by the Littles’ investment. Upon being introduced to Stuart, his new family members visibly display shock, before stuttering “He’s a… -dorable!”, avoiding the stigmatic term ‘mouse’. Their adoption of Stuart is increasingly problematic due to the unblemished benefits that he has over the resident pet, hinting to a hierarchy that appears to prioritise humans followed by anthropomorphic animals, pets and finally wild animals such as the ‘alley cats’ that are not domesticated. The less human or influenced by society the animals are, the further down this hierarchy they appear. This social order contradicts what the Littles ostensibly represent in their morality, as both Eleanor and Frederick are eager for Stuart to be accepted, but their almost disregard of Snowbell as an equal to Stuart or themselves does not support them as ethically sound. Furthermore, the general depiction of cats throughout Stuart Little furthers the problematical ethos of the film; a first instance being the difference in how the Littles communicate with their two resident animals. Whilst Eleanor will offer a hand for Stuart to stand upon, on the occasions that Snowbell is interacted with he is lifted from under his legs and carried in a way that allows him much less freedom to move. Also, whilst Stuart’s new mother converses with him in coherent sentences, she subjects her pet cat to tirades of disjointed sentences of incorrect English, as though Snowbell possesses the intellect of an infant. Both the adoption of Stuart and the treatment of both Snowbell and the ‘alley cats’ in the film contribute to an injustice concerning the portrayal of the whole animal community; as the film does not conceal the favouritism of humanised animals such as Stuart.

Many animated films can be recognised as highlighting the same issue of a hierarchized portrayal of humanity and animals. In Disney’s Dumbo (1941), a group of flamboyant crows discourage Dumbo from flying and ridicule his belief that he is capable of doing so. This cruel and malicious attack from the crows, who smoke cigars and cackle in the elephant’s face, has been perceived as a racial attack; with the genre of their featured song ‘When I See An Elephant Fly’ being reminiscent of the jive-style that surfaced amongst the African-American community in the 1930s. Moreover, a similar criticism has been made of Lady and the Tramp (1955), with its antagonists featuring two Siamese cats that bully the ‘Princess’ [3] Lady and contribute to an eerie nature of the film through their disturbing voices and unpleasant personas. Both Dumbo and Lady and the Tramp favour certain species of animals over others, contributing to the notion of a hierarchized portrayal of animals in modern cinema.

[1] The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture by Paul Wells (Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, New Jersey and London) p. 23

[2] The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture by Paul Wells (Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, New Jersey and London) p. 27

[3] “Propp identifies the attaining of a Princess as the typical goal of the folktale hero”: from ‘Introduction’, Fairy-Tale Transformations by Vladimir Propp https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=kY8XFN6smdsC&oi=fnd&pg=PA73&dq=propp+princess&ots=HOvzkeT9l8&sig=zwWNFEzz7wBIoE72gxafloXgC5s#v=onepage&q=propp%20princess&f=false p. 4