Introduction

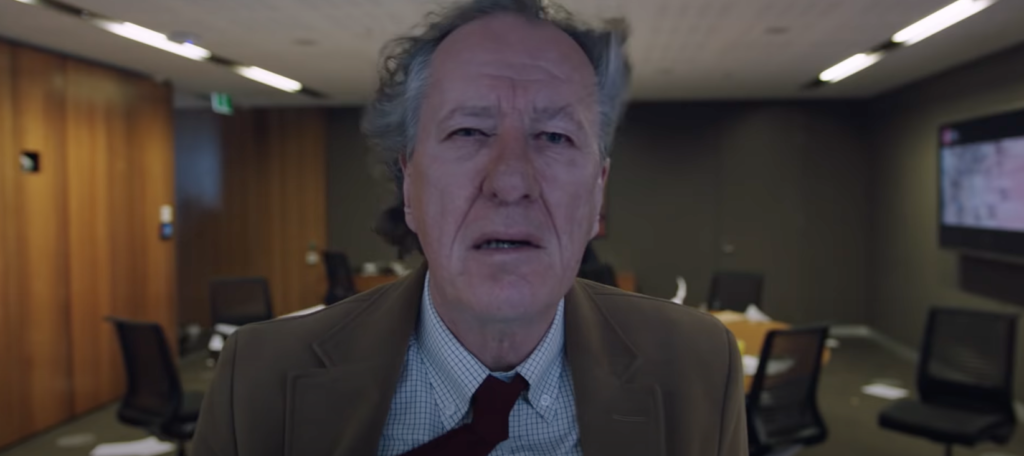

Storm Boy (2019) is an Australian film adapted from the 1964 children’s novel of the same name by Colin Thiele, explores the extraordinary bond between a young boy named Michael and his relationship with pelicans. The story unfolds with an adult Michael being troubled by the impending business deal in the company he founded. He was distressed since this deal has a potential to threaten the nature and animal life he cherished as a child. The initial scene, with the ominous stormy weather, starkly contrasts with the film’s other beautiful coastal scene settings, leaving a strong impact.

As the atmosphere turns dark and dangerous, adult Michael strides towards the window, symbolises that he will confront the environmental destruction. His gaze is fixed on a bird perched on a street light amidst the storm, while the conference room window is shattering. This powerful scene with a significant impact to initiate the exploration of intricate issues and relationships between human and nature depicted in the film.

Human-animal relationships

The film intricately explores various dimensions of human-animal relationships, emphasising the interconnectedness of animal life and humans, the human impact on nature, and the importance of empathy and compassion in the conservation of wildlife. Following a striking opening scene, Michael recalls his childhood in the past, a time when he and his father resided on an Australian beach, detached from the outside world. There he found three pelicans who had lost their mother that was a victim to hunters’ gunfire.

He persuaded his father to raise them in their house. One of those pelicans in particular, Mr Percival forged a profound bond with Michael, becoming an integral part of the family. Around the same time, Michael encounters Fingerbone, who has a Ngarrindjeri Aboriginal background.

Michael learned from him how Aboriginal people have historically coexisted with pelicans and nature in general. Those relationships form the core of the film’s exploration of the delicate balance between human and the natural world.

Figure 4: Fingerbone and Michael

Beautiful Friendship or Crossing the border?

The profound connection between Mr. Percival and Michael, as one of the major themes in the film, has a huge impact on shaping Michael’s life. After rescuing orphaned pelicans, Michael initially enjoyed the company with them. However, as the pelicans mature, his father insists that the pelicans must return to their natural habitat as wild animals. Understanding the necessity, Michael reluctantly releases them, sinking into solitude. To his surprise, one morning, he discovers Mr. Percival, a pelican he particularly considered part of his family, returning to his house. Intriguingly, Michael’s father does not object to him keeping Mr. Percival this time. Preceding Percival’s return, there is a scene where the father shares his grief about the loss of his wife and daughter with Fingerbone.

This moment suggests that his father, witnessing the pain of Michael, may have empathised with him and Mr. Percival’s family connection, promoting a change of mind.

While the film portrays the decision to keep Mr. Percival as a beautiful emotional one, scepticism arises about its appropriateness, especially considering the tragic fate that awaits Mr. Percival at the hands of a hunter. Shortly after Mr. Percival’s return, Michael’s father faces a life-threatening situation on the boat, close to being swallowed by the raging sea. Michael and Mr Percival cooperate together, successfully rescuing the father eventually. After that, the incident was on the news and the story of the remarkable relationship between the boy and pelican gained attention in the town.

Soon after their story earned widespread fame, Mr. Percival was shot by the hunter. While the blame for Mr. Percival’s tragic end unquestionably falls on the shoulders of the hunter, lingering doubts persist about Michael’s decision to keep the pelicans as a family may have crossed a line. There is a moral quandary especially considering that hunters had repeatedly threatened Michael by expressing their annoyance at him drawing attention by keeping the pelican as a pet, which are subject to hunting for them.

“Bird like him, never dies.”

Towards the end of the film, there is a scene where the adult Michael imparts to his granddaughter the wisdom that “bird like him, never dies”. This line, however, raises questions about accountability. It seems as if Michael, in acknowledging the magnificence of natural wildlife, although he was not exempt from those who misunderstood the balance within the human-animal friendship and the responsibility associated with preserving animal lives. The story’s portrayal of Mr. Percival’s murder as a beautiful story without addressing the potential burden on the consequence that Michael and his father’s decisions lead introduces a thought-provoking and somewhat questionable dimension to the story.

Business achievements and environmental preservation

Beyond the connection between the pelican and Michael, the film deals with intricate moral dilemmas surrounding environmental conservation and business, constituting another central theme. However, this theme seems to overcomplicate the story, introducing ambiguity and weakensweakens the overarching standpoints of the film’s respect for nature. When an adult Michael wrestles with the situation of his company striking a deal with a mining company that poses a potential threat to the Australian coastal environment, the granddaughter, concious about environmental conservation and apprehends about the potential consequences, passionately urges him to reconsider.

Although he initially intends to delegate the decision to other executives of the company, Michael is swayed by her persuasion and leaning towards discontinuing the deal, while reflecting on his past experiences along the coast.

Figure 8: granddaughter talking to Michael

The narrative, however, takes an unexpected turn. Instead of actively pursuing his son, current top of the company, to abandon the deal, Michael decides to extend the meeting, placing the destiny of the company’s agreement in the hands of his granddaughter, who holds a 25% stake. The decision not only prolongs the ambiguity but accentuates Michael’s tendency to absolve himself of responsibility. This makes it harder for audiences to identify the film’s message and stance about accountability and responsibility, especially in decisions with significant implications for environmental preservation.

Storm Boy (1976)

In the 2019 adaptation of Storm Boy, while Michael formed the real relationship with the pelicans in his childhood, he appears irresponsible in dealing with both the Mr. Percival incident and the fate of the company he founded. These aspects are depicted in a distinct way when compared to the 1976 version film of the same name.

While those two versions share the same streamline with the same reference to the 1964 book, the most notable difference lies in the absence of the contemporary adult Michael in the 1976 version.

Unlike the 2019 version, the 1976 version presents Michael’s life with his father and the pelicans along the Australian coast throughout the film without the back-and-forth timeline. This absence of present-day scenes in the older version means that the social issue that the latest version raised where Michael grapples with the tension between business interests and environmental ethics is not discussed in the older version. Instead, the 1976 version concentrates on the formative period in Michael’s life, offering a more profound exploration of his relationships with both his relationships with both his father and the pelicans.

Fingerbone in two versions of the film

While the two film versions differ in some parts of their narratives, the key similarity is the pivotal role played by Fingerbone in both versions. He embodies the wisdom and deep innate understanding of the way people of the Nagarrindjeri Aboriginal community have respected pelicans. His portrayal in both films illustrates his cultural role as a mentor of Michael, shaping his understanding of the importance of respect and coexistence with those pelicans and natural lives in general, with a delicate balance of values. Although Michael looks a little wary about Fingerbone when he first talks to him, they form a natural bond, transcending their differences in age and background. Fingerbone’s character contributes to imparting a profound sense of respect and responsibility for environmental conservation.

However Fingerbone plays the major role by conveying those profound cultures in both versions of the story, the way that the newer version of the 2019 film presents “Aboriginal culture” raises questions. Throughout the film, he is depicted as a mysterious figure who came out of nowhere with unexplained aspects of his personal life such as his place of residence and family. For instance, when Mike asked him where he comes from, he just said “Just about.” While Fingerbone shows Michael how to coexist with pelicans effectively, the film falls short of delving deeper into Fingerbone’s culture, failing to showcase various Aboriginal ways of life beyond pelican interaction. He remained to be portrayed as an “indigenous” figure who has a profound but different, ancient culture, providing limited insight into his broader cultural practices.

Michael respects how Fingerbone treats pelicans and he enjoys spending time together with pelicans and Fingerbone. However, the film primarily focuses on the bond between Michael and pelicans, sidlining Fingerbone’s Aboriginal traditional culture and his individual personality, which seems that Fingerbone’s Aboriginal traditional culture is used just as a tool so that Michael can help pelicans.

The way that he is presented in the film of 2019 version seems that Fingerbone’s Aboriginal traits are put into “wild” category and aligns his character with wildlives like pelicans, potentially perpetuating stereotypes associated with “othering.” While the film successfully captures the beauty of nature and wild pelicans, more careful attention should be paid to the representation of certain cultures especially those which often are subject of “othering” so as to ensure appropriate and respectful portrayal.

In contrast to the 2019 version, Fingerbone is portrayed as a character with even deeper cultural depth in the 1976 verstion. Unlike the latest version, Fingerbone in the 1976 version less actively mentors Michael through explicit teachings. Instead, he lives his own life with dignity, intervening to help Michael only when necessary. The way he appreciates nature also appears different. In this older version, Fingerbone always carries a gun, symbolysing his understanding that, despite his love for the land’s nature, there are boundaries in interacting with the magnificence of nature and wildlife.

This choice reflects Fingerbone’s nuanced appreciation of the delicate balance between acknowledging the interconnectedness of the natural environment and recognising the limitations of human interaction with it.

“Bird like him, never dies”

same line, but by Fingerbone this time

Furthermore, in the 1976 version, the line “bird like him, never dies” is attributed to Fingerbone, whereas in the 2019 rendition, the same line is given to the adult Michael. It holds significant impact as it serves as the final line in this version of the film. These words encapsulate Fingerbone’s cultural depth, his profound understanding of nature, and the genuine care he holds for Michael. They symbolise Fingerbone’s nobility, emphasising the film’s thematic elements of cultural richness and the enduring connection between humans and nature.

Conclusion

In essence, although the responsibility of characters like Michael and his father in their impacts on environmental protection was insufficiently addressed particularly in the 2019 film, both versions of the film vividly portray the beauty of the coexisting human-animal relationship and grandeur of nature. The story emphasises the importance of empathy and compassion for achieving an interrelation between animal life and humans. Furthermore, by presenting Fingerbone Bill, with an Aboriginal background, the films align the survival of their tradition with the preservation of nature and wildlife. While the presentation style to project him as a wild presence especially in the 2019 film remains questionable, his presense allows the audience to contemplate another form of human-animal relationships, such as the connection of Aboriginal culture with the natural world and the significance of wildlife conservation.

This article critically examines the message conveyed by the film, particularly by scrutinizing the newer version of Storm Boy. By juxtaposing it with the older version, we can understand a profound respect for wildlife and traditional culture in narratives. The 2019 adaptation delves into the intricate issues such as the dilemma of modern development and the conservation of the natural environment, adding complexity to the narrative. Still, it is worth noting that the issues raised, particularly in this new version, remain unresolved, leaving room for improvement in the portrayal. While the film’s central stance on the natural environment might be obscure in the newer version, both films excel in portraying the magnificent nature through beautiful cinematographically techniques.

Bibliography

Good Deed Entertainment. “Storm Boy (2019) Official Trailer HD, Jai Courtney, Finn Little Family-Friendly Movie,” Youtube Video, February 28, 2019, https://youtu.be/GZlOXR75Bx4?si=dFbGr9LqmJE4rIY9

National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA), “Storm Boy (1976) – original trailer,” Youtube Video, August 25, 2016, https://youtu.be/siKxwFpYEQc?si=UW31RfQ67TxNxu5k

Safran, Henri, dir. 1976. Storm Boy (South Australian Film Corporation)

Screen Australia, “Storm Boy – Behind The Scenes”, January 16, 2019, https://youtu.be/O1u1PSs1H6A?si=oTYmMFkKYwO9yVfi

Seet, Shawn, dir. 2019. Storm boy (Sony Pictures)

Further Reading

Bousé, Derek. 2000. Wildlife Films. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Cox, Laura, and Tamara Montrose. “How Do Human-Animal Emotional Relationships Influence Public Perceptions of Animal Use?” Journal of Animal Ethics 6, no. 1 (2016): 44–53.

Stoddard, Jeremy, Alan Marcus, and David Hicks. “The Burden of Historical Representation: The Case of/for Indigenous Film.” The History Teacher 48, no. 1 (2014): 9–36.