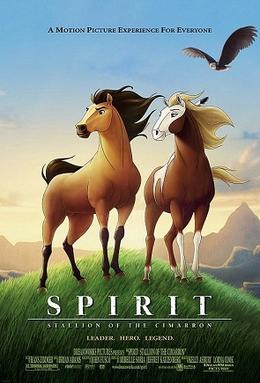

The eponymous character Spirit in Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron (2002)[1] is a stallion who lives freely in an area that would come to be known as the ‘Old West’. Unusually for an animated film, none of the animal characters partake in any spoken dialogue with eachother -instead expressions, naturalistic animal sounds and movement are used to convey action and discourse, with music and occasional narration expressing Spirit’s own consciousness to the audience. The film documents his struggle to regain his freedom after he is captured first by white European settlers and then by Native American Indians, the latter with whom he starts to feel an emotional bond. Ultimately he returns to his homeland to rule his herd as a free horse.

Spirit is a hybrid genre combining the popular form of animation with the Western, a form that has declined in popularity significantly since the mid-twentieth century.[2] In choosing to combine the two forms the animators can be seen to be bringing a new life and relevance to what is often seen as a dated genre. Not only do they animate it, and thus appeal to younger audiences who may not otherwise watch Westerns, but they present it from the view of a horse. This placing of the horse as a protagonist in a Western serves to give a voice to a previously silent character. Westerns are most often concerned with the battle between good and bad, civilisation and nature.[3] The horse as a protagonist in a western must therefore engage directly with these issues and as such becomes a part of the moral conflict, placing it into the role previously established as a human one, despite the film’s endeavour to portray Spirit as a free creature. This tension is compounded as Spirit, though presented as a free creature is ultimately a cartoon; created by humans in a mechanical and industrialised process which is a modern art form.[4]

The filmmakers made a conscious effort to depart from the norm[5] when they decided to not have animals speak. They aimed to create a more realistic representation of the horse, with animators studying equine anatomy and movement patterns, notoriously difficult to draw[6], to create a more naturalistic portrayal. [7] The opening scene of horses running (02:29) is a visually stunning example of this, as it looks incredibly similar to cases of real wild horse herds. Plot and discourse between characters (besides humans, who talk themselves) are shown through body movements, expressions and realistic sounding animal noises.

When Spirit enters the Fort after his first capture by wranglers his eyes widen and he cowers (19:00), and in doing so the audience can clearly interpret that he feels horrified by the suppression and uniformity of the horses in the fort in contrast to his own herd. There is a

camera shot of his face with his eyes gazing down, shortly followed camera shot at the low level of the horse’s legs which march in complete synchronisation. Through simply Spirit’s action and expression the audience comes to understand his emotions and this is constant throughout the film, yet there is also the inclusion of narration and of songs to reinforce Spirits feelings, often unnecessary to the audience’s understanding of the plotline. When trapped in the Fort, Spirit looks to the stars with a sorrowful look on his face; just as his herd do at the same time in an obvious parallel of emotion. This is enough to tell the audience that they are thinking of each other, but via overhead narration Spirit adds “My heart galloped through the skies that night. Back to my herd, where I belonged. And I wondered if they missed me, as much as I missed them” (my emphasis -25:00). This narrative example indicates a more poetic and philosophical element to Spirit as he considers his separation from his herd, not only his emotional pain. It also indicates his intellectual level as he uses a metaphor pertaining to his own physical status as a horse. This serves to complicate Spirit’s character to something that is not just a horse who suffers emotional pain from his separation, but one as who has a conscious awareness of his situation and of his pain.

The film’s musical numbers are also used in a similar way. The songs were performed by Grammy Award winning rock star Bryan Adams. The filmmakers remarked that using Adams, because of his rock star credentials, added to Spirit’s ‘playful’ and ‘cocky’ sides of his personality, [8] personality traits that can be associated with a Western hero. The song ‘Get Off Of My Back’ (22:20) is the song that encapsulates this personality, and plays during Spirit’s rebellion as the humans try to ride him. The audience sees that Spirit’s interactions with these men are cocky, playful and violent by his ferocious bucking action juxtaposed with his playful whinnying. The music serves as an added element that is therefore independent from the understanding of the plot, but what it does add is Spirit’s contemplation of the events.

The use of celebrities also adds an unmistakable ‘human’ quality to the film, in that the audience may recognise particular people and engage with them, rather than the character they are trying to portray. The narration is provided by Academy Award Winner Matt Damon. Damon, Adams and Hans Zimmer, the score composer, are well-known in both their respective artistic fields and in popular culture. Especially with the use of Adams, these celebrities are used in the film as means to display Spirit’s personality, while also being used to increase interest in the film among audiences, a technique becoming popular in animated films.[9] This indicates the necessity of human presence to add interest to the film in a way that could not be achieved without it, and lessens the ‘other-ness’ of Spirit as his singing voice is one that is easily recognisable as a famous human one. This makes it hard to separate Spirit’s horse personality traits from a human presence.

The very fact that Spirit is an animated horse poses problems when trying to show him naturalistically as he is created by an industrial and labour intensive process of animation. The film makers stress how they wanted a more naturalistic portrayal then usual in animation features and to a large extent this is fulfilled. Nevertheless the animators use small ‘cheats’ in creating the animals. One such example is that the animators add eyebrows to the horses, when in reality horses only have eye ridges.[10] Eyebrows are incredibly useful to animators in conveying expression, but physically a human attribute, not a horse one. The addition of eyebrows shows that the animators seek to convey emotion in a way its audience would understand easily in relation to themselves, not how a horse would naturally show emotion.

Understanding Spirit as an active figure is possible, but the filmmakers choose to add narration and music to make him a more intellectual, contemplative being. These added dimensions helps the audience to empathize and relate more to him as a character than they would if he was seen as something as separate and as unknown as animals often are. Being and acting like a horse is not enough for the film makers, he must have a combination of intellectual and emotional capabilities in order for him to engage with issues of morality vital to fulfil the Western hero’s role. It is this endeavour that helps Spirit to become a Western hero in that he has to make a conscious and moral choice between what he sees as right and wrong.

By not speaking in the film itself, Spirit retains his sense of ‘otherness’ to the human characters even as he bonds with one of them. He bonds with Little Creek only when Little Creek shows a love and respect for him that has nothing to do with domination. Little Creek respects Spirit to make his own choice to let him ride him (01:03:33) in contrast to the white settlers in the film who view riding Spirit as a symbol of their own power. Spirit’s relationship with Little Creek is an unspoken bond built on trust in each other’s actions, which stands in contrast to the relationship between Spirit and the audience which grows largely in part to Spiri’ts narration and the songs. The film therefore indicates that this bond between animals and humans which does not rely on language is one that cannot be gained through a movie screen, but only physical relationships with horses.

The lack of language communication in the film between the human and animal characters is similar to that in Ratatouille (2007), where humans initially pose a threat to the welfare of the animals. Remy the rat protagonist feels separated from humanity but comes to bond with a human character, Linguini the garbage boy, without the use of language. The characters find ways of communicating to each other without spoken language and form a relationship that is mutually beneficial; Remy controls Linguini to realise his own dreams of cooking, while Linguini benefits from the rats superior cooking skills and earns the reputation of a talented chef. In Ratatouille the relationship is first based on mutual benefits, and from this a friendship is formed, yet in Spirit, horse and man earn each other’s respect and become friends before benefitting from the relationship by escaping from the colonel.

Further Reading and Internet Sources

- Burt, Jonathon, Animals in Film (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2002)

- Burt, Jonathan, Madagascar, Eric Darnell and Tom McGrath (Eds.), (Dreamworks,2005) https://www.animalsandsociety.org/assets/library/620_reviewsection.pdf (accessed 24/03/2013)

- Buscome, Edward and Pearson, Roberta E. (Eds) ‘Introduction’ in Back in the Saddle Again: New Essays on the Western (London: British Film Institute, 1998), pp. 1-7

- Clifford, Laura and Clifford, Robin, ‘Review- Spirit – Stallion of the Cimarron’ https://www.reelingreviews.com/spirit.htm (accessed 23/03/2013)

- ‘The Making of Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron Part 1 of 2’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMSQYl5shRo (accessed 24/03/2013)

- ‘The Making of Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron Part 2 of 2’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eRYttvufZMo (accessed 24/03/2013

- Meslow, Scott, ‘How Celebrities Took Over Cartoon Voice Acting’ in The Atlantic 28-10-2011 https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/10/how-celebrities-took-over-cartoon-voice-acting/247481/ (accessed 24/03/2013)

- Mitman, Greg, Reel Nature: America’s Romance with Wildlife on Film (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999)

- Mizuta-Lippit, Akira, Electric Animal: Toward a Rhetoric of Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000)

- Newman, Kim, Wild West Movies: How the West was Found, Won, Lost, Lied About, Filmed and Forgotten (London: Bloomsbury, 1990)

- Sisk, John P., ‘ The Animated Cartoon’ in Prairie Schooner Vol. 27, No. 3, Fall 1953, pp. 243-247

- Walker, Elaine, Horse (Reaktion Books Ltd, 2008)

- Wells, Paul, The Animated Bestiary: Animals, Cartoons and Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008)

- https://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html (accessed 23/03/2013)

[1] Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron Dir. Kelly Asbury, Lorna Cook, DreamWorks, 2002

[2] Edward Buscome, and Roberta E. Pearson (Eds), ‘Introduction’ in Back in the Saddle Again: New Essays on the Western (London: British Film Institute, 1998), p. 1

[3] https://www.filmsite.org/westernfilms.html (accessed 23/03/2013)

[4] Burt, Jonathan, Madagascar, Eric Darnell and Tom McGrath (Eds.), (Dreamworks,2005) https://www.animalsandsociety.org/assets/library/620_reviewsection.pdf (accessed 24/03/2013)

[5] ‘The Making of Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron Part 1 of 2’ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMSQYl5shRo (accessed 24/03/2013)

[6] Clifford, Laura and Clifford, Robin, ‘Review- Spirit – Stallion of the Cimarron’ https://www.reelingreviews.com/spirit.htm (accessed 23/03/2013)

[7] ‘The Making of Spirit’ Part 1

[8] ‘The Making of Spirit’ Part 1

[9] Scott Meslow, ‘How Celebrities Took Over Cartoon Voice Acting’ in The Atlantic 28/10/2011 https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/10/how-celebrities-took-over-cartoon-voice-acting/247481/ (accessed 24/03/2013)

[10] ‘The Making of Spirit’ Part 1