That fear of death. Do you feel it? Are you scared now?

– Sonnie

Content warning: sexual assault, female violence, abuse

Netflix’s animated anthology, Love Death & Robots, first aired in 2019, enticing viewers through a display of episodically unique art styles and stories. Created by David Fincher and Tim Miller, the series provided a creative leeway given to each episode’s directors. Despite this, the series seemed unable to break free of one fixation – the consistent, sexist depictions, female violence and sexualisation. WIRED news editor, James Temperton, writes: “Here, Love is the sexual abuse of women; Death is the physical abuse of women and Robots are either hulking evil things or smart-talking cuties[1].”

Good Hunting’s depiction of a fox spirit

Jibaro’s siren is beaten and her skin ripped

The Witness’ heroine runs half naked from a murderer

Evidently, even when animality and non-humans are brought into the scene, these issues can never stay out of the limelight for long. This is rooted in the anthology’s first episode, Sonnie’s Edge, which uses animalisation to represent Sonnie’s renegotiation of identity and revenge. Set in a cyberpunk Britain it follows Sonnie, the only female pilot, who controls a beastie[1] named Khanivore through neurological links, participating against male pilots in an underground fighting ring. When she refuses a bribe to lose the next match, her friend explains why. Sonnie was gang raped and attacked by a group of estate men, so these fights allow her to get back at those who wronged her. In a blood-shedded twist at the end of the episode, Sonnie reveals that the assault left her body in tact, but her skull broken.

Her brain needed a new host.

So she became Khanivore.

You wanna know my edge? Every time I step into that ring, I’m fighting for my life. That fear is my edge.

– Sonnie

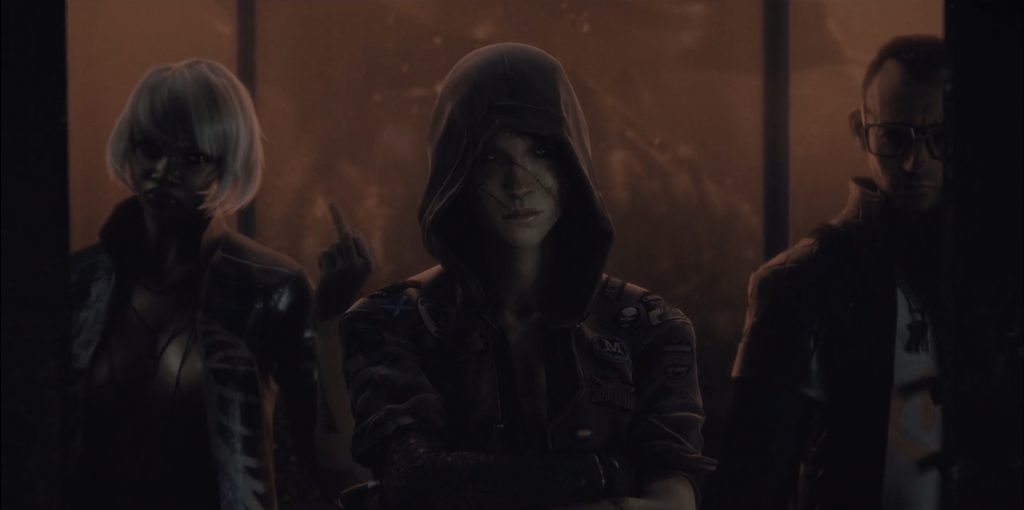

Ivrine, Sonnie and Wes

At its core, Sonnie’s Edge creates an empowering, feminist message of a woman who found her way after a traumatic assault, recovering her identity, strength and resilience through animalisation. However, its use of the rape-revenge sub-genre in line with animality leaves noticeable holes throughout this episode, raising questions in regards to what message the revenge portrays, specifically about women and their identities. This will be further explored through the two main animal identities prevalent within Sonnie’s Edge: the snake and the beasties.

Fig 1: A cobra, the specific snake species represented in the episode. Image credit: CNN

Fig 2: Sonnie’s beastie, Khanivore

Fig 3: Simon’s beastie, Turboraptor

Throughout the episode, Sonnie’s animalisation through visual design is evident from the beginning, specifically via snakes. In a wide shot from the opening, viewers see a man signalling Sonnie’s van to a stop, as he pulls out a UV light. This cuts to another wide shot of the side of the van, revealing the fluorescent snake pattern which is hidden in normal lighting. The camera remains still as the van moves into the building, and viewers see the pattern progress through the UV light, vanishing once it is outside its range, like a snake viewed at night through a torch, sliding through the grass. Here, by wrapping the van’s side in a snakeskin pattern, this visual design choice embodies the idiom, “a wolf in sheep’s skin”. The significance of this animalisation – being visible only under UV light – is that it evokes a sense of deceiving perception, thus mirroring Sonnie herself. Due to the rape, and being a woman in an all male, fighting ring, Sonnie is perceived as weaker and constantly troubled. This misconception allows her to catch her opponents off guard, like a snake striking unexpected prey. Consequently, this evokes an empowering depiction of female strength, amplified by the non-diegetic, blaring sound which briefly rings out like a warning sign as the van drives past. In a society where many women lack confidence to pursue opportunities which are stereotyped to be better accomplished by men[1], Sonnie’s symbolism through animality represents an inspiring message of unyielding resilience, regardless of sexist perceptions.

Fig 4: The man’s UV light reveals the snakeskin patterns alongside the van

Fig 5: The pattern of a real snakeskin. Image credit: Peakpx

Fig 6: A cobra tattoo is marked on Sonnie’s chest

Alongside the visual design of the van, Sonnie’s Edge explores renegotiation of identity through Sonnie’s own animalised appearance. Clarke (2008) defined identity renegotiation as the following: “The act…involves three steps: understanding the event, accepting the trauma, and recovering one’s identity by adapting what was to define what is[1].” The episode adheres to this, specifically in the scenes leading up to the fight. Whilst Sonnie prepares to switch into Khanivore (at this point, viewers are still under the impression that she links neurologically to control her beastie, like the others), an array of snakes is displayed tattooed onto Sonnie’s body, which – like the van – is only visible under UV light. As Sonnie finally switches into Khanivore, there is an extreme close up shot of her face, emphasising and highlighting the details of her animalistic markings. Here, the snake scales are centrally framed, covering the entirety of Sonnie’s nose, and overlapping but not concealing the scars inflicted by the estate men.

Fig 7: An extreme close up of Sonnie’s face. She’s ready.

This choice in an animalised, visual design reflects the recovery aspect of identity renegotiation. Specifically, as creatures that shed their skin, snakes have long been symbolised with rebirth, immortality and healing[1]. Therefore, by associating Sonnie’s identity with that of a snake, animality is used to reflect her recovery and adaptation. The jagged, harsh appearance of the scars forced onto her, serve as visual reminders of that night, but the overlapping, serpentine markings symbolise her rebirth and renegotiation of identity, refusing to let the trauma centralise itself in her image and self perception. This is echoed later, when Sonnie refutes the statement her friend had made prior, revealing that the rape has nothing to do with her strength. Consequently, the significance of Sonnie’s animalisation via a snake, and the rebirth symbolism behind it, combats a common issue within filmography and society in general, whereby rape survivors are permanently associated with labels of being damaged, mentally destroyed, and their identity or motives centralised around the trauma[2].

ARE YOU READY?

– Announcer

Through diegetic sound, the roar of both crowd and commentator erupts in excitement, as the battle commences and Sonnie’s Edge… … contradicts its own protagonist.

In a callback to the issues mentioned in the introduction, the pivotal battle fumbles its episode’s own message, indulging in the conventions of a rape-revenge fantasy sub-genre. Though Sonnie states:

Rape? Yeah it’s not that. They can’t see past it, no one can. But it ain’t what gives me my edge – angry little girl, out for revenge.

– Sonnie

Fig 8: Sonnie reveals, in an intimate exchange, the truth of her ‘revenge’

Fig 9: Khanivore’s P.O.V shot from within the tank

The battle itself undoubtedly serves as an animalised depiction of Sonnie’s rape, largely shifting the viewer’s perspective into that belief which Sonnie despises. Rape-revenge fantasy generally follows a female protagonist who seeks brutal, unrealistic revenge after male exploitation, and often includes explicit depictions of sexual assault – prompting many to question the necessity of it, due to risks of upholding the male gaze[1]. In two P.O.V shots, the viewer becomes immersed as Khanivore, symbolising the shift from human to beastie, as we finally see her and Turboraptor (her opponent) in all their glory. It is evident through visual design and framing, that these beasties are animalised reflections of their pilots. One tracking shot follows Khanivore’s tail, as – though deadly – it captures her feminine elegance, gracefully sliding across the audience. A close up shot whilst she analyses Sonnie, establishes the white and dark contrast of her body, mirroring Sonnie’s grey toned skin and white top. In comparison, Turboraptor and his pilot’s (Simon) large, masculine physiques are reflected in a wide shot of the tunnel. As Turboraptor emerges, his body consumes the entire frame, dominating the scene. The shot cuts to a close up as he curls his fist in a stereotypically masculine, display of strength.

Fig 10: Khanivore’s tail sweeps past the crowd

Fig 11: An up close of the beastie’s face

Fig 12: Turboraptor dominates the frame

Fig 13: The beastie’s clear display of masculine power

As the fight precedes, the animalisation of gendered identity remains persistent through diegetic sound. Khanivore’s attacks are audibly quieter than Turboraptor’s, resembling a swift flurry of light yet sharp cuts. In comparison, Turboraptor’s attacks and movement are audibly different, instead resonating with deep, loud thuds and the rough grinding of rocks. Alongside the visual design, this use of sound embodies the differences between Sonnie and Simon via animalisation. The brutal nature of the fight is made disturbing through its clear resemblance to the human counterpart, inflicting images of female violence especially when Khanivore’s attack fumbles. In this scene, a slow motion shot of Khanivore builds up suspense as she is about to land a lethal blow, spinning gracefully into the air. The diegetic roars and non-diegetic music becomes muffled into a blur of insignificance, placing all the focus onto the power and beauty of Khanivore. However, the camera cuts to a wide shot as the scene resumes its normal speed, and Turboraptor dominates the right side of the frame. His occupation of a much larger volume than Khanivore, mirrors the displacement of power back to him as he manages to grab onto her tail.

SURPRISE MOTHERFUCKERS!

– Simon

Fig 14: Turboraptor manages to grab Khanivore’s tail

Fig 15: Simon roars in excitement

Simon’s diegetic, masculinely deep voice booms through the arena as a tracking shot follows Khanivore, flung by Turboraptor into the wall. Whilst he grabs her by the neck, another tracking shot is magnetised to his fist – symbolic of his brutal, physical strength – as he pulls his arm back and punches Khanivore into the wall. This impact is captured through the use of a camera shake, as Khanivore collides and breaks off part of the wall. The disturbing echoes of female violence inflicted by men through animalisation, reaches its peak of uncomfortable portrayal when Turboraptor reveals his secret weapon – a hidden blade.

Fig 16: Khanivore is flung against the wall

Fig 17: Turboraptor prepares a lethal punch

Fig 18: He reveals a hidden blade

Though Sonnie’s rape is never shown on screen, the following scene seemingly serves as a stand-in reenactment. Having used his blade to dismember Khanivore’s tails, this mirrors the estate men who had also used blades to cut Sonnie up. A wide shot from behind Turboraptor’s feet, lines him up with a vulnerable Khanivore, trying to crawl backwards. Through mise-en-scene, the dark lighting captures Turboraptor almost as a silhouette, evoking an ominous depiction with unknown intentions. As Khanivore attempts to run, Turboraptor grabs her by the throat and pins her against the wall, whilst a close up shot filmed in slow motion depicts his hand gripping the wall in a suggestive manner. This cuts to another, close up slow motion of the blade’s phallic resemblance as it penetrates Khanivore, whilst Turboraptor thrusts forwards in an above shot. The tantalisingly slow motion of this scene, forces viewers to endure this uncomfortable reenactment of Sonnie’s rape, emphasising the horror that she must endure this again.

Fig 19: The suggestive, close up shot

Fig 20: Khanivore is penetrated with the blade

Fig 21: An above angle shot of the two

Except she does not.

In a classical moment of the rape-revenge fantasy genre, Khanivore snaps back, mirrored in the cut off of non-diegetic, atmospheric sound. She plunges her head through Turboraptor’s neck, and rips his head off. By definition of its genre, the violence in this revenge elevates its satisfactory conclusion. However, the animality of the rape scene, as well as in the beastie counterparts of the pilots, evokes a double – edged sword effect. Where some may find the scene rewarding, this before vs after style depiction, in light of her animalisation through Khanivore, leaves a substantial stain in the concept of her identity renegotiation and revenge. The mini twist as Khanivore fights back suggests that she can now defend herself, unlike previously, due to access to her animalisation. Though it seems satisfactory, it is only brief, as it implies that the injuries Sonnie had sustained prior, were at such brutal levels because she was unable to fight back. However, now by replacing her identity through animalisation and embracing this brutal nature, she can fight the men who harmed her. Rather then reclaiming agency over her identity, Sonnie seems to have been forced to adapt to survive. The self she was previously was apparently weak, but with all that animalisation she has undergone she can now fight back.

But for what cost? Her humanity is forcefully gone, and her life is at stake just to make a living. What does it suggest for the other women in this cyberpunk Britain, that are unable to access the animalisation and beastie which Sonnie has? These questions which arise remain unanswered after the episode, fulfilling one of the main criticisms of the genre. These are that little is ever explained about the heroine’s life after the revenge is exacted, whilst graphic exposure prevents little opportunities for new perspectives on the heroine outside of her trauma[1].

Fig 22: Victory, as Khanivore rips the head off of Turboraptor

To conclude, Sonnie’s Edge uses animality and its symbolism to signify the importance of reclaiming agency and renegotiating identity within the aftermath of sexual abuse. However, the representation of rape-revenge in the pivotal beastie fight, fails to follow this initial portrayal, as the animalisation of Sonnie’s trauma suggests that she did not reclaim her agency of identity – instead, having to undergo drastic transformation just to survive in such a bleak world. Though unintentional, the shoehorned, animalised recreation seemed to exploit Sonnie’s rape for a brief moment of revenge satisfaction and entertainment, failing to account for her life and struggles outside of winning as Khanivore. This issue echoes throughout Love Death & Robots, persistently depicting female abuse, sexualisation and revenge, with little satisfaction or focus on the heroine’s identity outside of entertainment.

Footnotes:

[1]Sophie Talbert, ‘Promising Young Women: Contemporary Case Studies in the Rape Revenge Fantasy Subgenre of Feature Films’ (2021) p. 21, in Honors Thesis Spring 2021 https://repository.flsouthern.edu/items/6e897be2-a4e4-4668-9b40-7a59bc49f985

[1] Sophie Talbert, ‘Promising Young Women: Contemporary Case Studies in the Rape Revenge Fantasy Subgenre of Feature Films’ (2021) p. 3, in Honors Thesis Spring 2021 https://repository.flsouthern.edu/items/6e897be2-a4e4-4668-9b40-7a59bc49f985

[1] Kristen M. Stanton, ‘Snake Symbolism & Meaning & the Snake Spirit Animal’, UniGuide, 2022https://www.uniguide.com/snake-symbolism-meaning-spirit-animal

[2] Jo Aine Clarke, ‘A Constant Struggle: Renegotiating Identity in the Aftermath of Rape’ (2008) p. 55, in Graduate Theses and Dissertations https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/181

[1] Jo Aine Clarke, ‘A Constant Struggle: Renegotiating Identity in the Aftermath of Rape’ (2008) p. iv, in Graduate Theses and Dissertations https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/181

[1] Dina Gerdeman, ‘How Gender Stereotypes Kill a Woman’s Self-Confidence’, Harvard Business School, 2019 https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/how-gender-stereotypes-less-than-br-greater-than-kill-a-woman-s-less-than-br-greater-than-self-confidence

[1] Beasties refer to biologically engineered beasts, controlled through linking neurologically to its brain. Those who control them are known as ‘pilots’

[1] James Temperton, ‘Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots is sexist sci-fi at its most tedious’, Wired, 2019 https://www.wired.co.uk/article/love-death-and-robots-review-netflix

Further reading:

Berridge, Susan, ‘Teen Heroine TV: Narrative Complexity and Sexual Violence in Female-Fronted Teen Drama Series’, New Review of Film and Television Studies, 11.4 (2013), 477–96

Bradshaw, Callum, ‘The sexualisation in Love, Death & Robots overshadows the high class animation’, Epigram, 2019 https://epigram.org.uk/2019/03/27/love-death-robots/

James, Deveryle, “A Zoo of Lusts … a Harem of Fondled Hatreds”: an Historical Interrogation of Sexual Violence Against Women in Film (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2011)

McWilliam, Kelly, and Sharon Bickle, ‘Re-Imagining the Rape-Revenge Genre: Ana Kokkinos’ The Book of Revelation’, Continuum (Mount Lawley, W.A.), 31.5 (2017), 706–13

Robinson, Abby, ‘Netflix’s Love Death + Robots has one very big problem and it’s not okay’, Digital Spy, 2019 https://www.digitalspy.com/tv/ustv/a26856709/love-death-and-robots-netflix-sexist-misogynistic/

Bibliography:

Clarke, Jo Aine, ‘A Constant Struggle: Renegotiating Identity in the Aftermath of Rape’ (2008) in Graduate Theses and Dissertations https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/181

Gerdeman, Dina, ‘How Gender Stereotypes Kill a Woman’s Self-Confidence’, Harvard Business School, 2019 https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/how-gender-stereotypes-less-than-br-greater-than-kill-a-woman-s-less-than-br-greater-than-self-confidence

Stanton, Kristen M., ‘Snake Symbolism & Meaning & the Snake Spirit Animal’, UniGuide, 2022https://www.uniguide.com/snake-symbolism-meaning-spirit-animal

Talbert, Sophie, ‘Promising Young Women: Contemporary Case Studies in the Rape Revenge Fantasy Subgenre of Feature Films’ (2021) in Honors Thesis Spring 2021 https://repository.flsouthern.edu/items/6e897be2-a4e4-4668-9b40-7a59bc49f985

Temperton, James, ‘Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots is sexist sci-fi at its most tedious’, Wired, 2019 https://www.wired.co.uk/article/love-death-and-robots-review-netflix