DreamWorks Animation’s Shark Tale plays with the binary of shark/fish through the characterization of Lenny the vegetarian shark and his performativity of conventionally human gender stereotypes. The family animation draws attention to the common opinion of meat eating as conventionally masculine, relating to an acceptance of violence, and vegetarianism as typically associated with femininity, empathy and compassion (Carol J. Adams, The Sexual Politics of Meat).[1] It is through this categorization that Lenny’s character is formed, and is why his behaviours as a male vegetarian are accepted as effeminate or “camp”.

With the shark species being stereotypically classed as a violent, unscrupulous, meat-eating creature, Lenny’s choice to have an ethical viewpoint on the consumption of other animals, as well as being friendly with species lower down the food chain than himself, marks him as decidedly different from other shark characters.

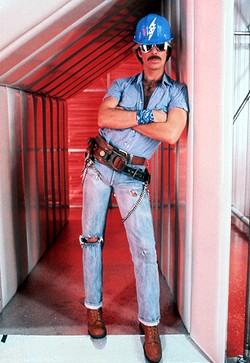

The scene in which we are introduced to Lenny’s stereotypically “camp” alter ego, Sebastian, sees a large development in the stereotypical idea of vegetarianism as a typically feminine value. Lenny flamboyantly emerges from behind a curtain wearing a utility belt, a ‘scarf’ made from police tape, and is painted blue and white from top to bottom. Upon entering the shot, the shark announces himself in a sing-song voice as, ‘Sebastian the whale washing dolphin’.

The theatrical nature of Lenny’s unveiling directly links to the performative nature of gender roles and their expectations. The representation of these stereotypically “camp” behaviours embodied in a conventionally ‘violent’ species makes Lenny’s character the perfect example of a comical satirization of established masculine gender roles.

Dolphins, although still carnivorous like sharks, are somewhat less threatening than the shark species, and thus, Lenny’s choice to appear as one can be understood by audiences of all ages to be a more acceptable friend to a fish. However, Lenny’s resemblance to a member of the 1970s disco group, the Village People, is a reference seemingly used to provoke a comedic response amongst the adult audience specifically.

Despite this adult reference, Lenny’s transformation brings an overall comedic value to the scene that can be recognized by audiences both

young and old. Lenny’s “camp” performance ins of breaking a tension created by the heterosexual, romantic-comedy style argument between Oscar and Angie. Throughout the film, Lenny is used as a comedic foil character to Oscar the cleaner wrasse fish, a common role for homosexual characters throughout film and television. His effeminate reveal heightens the heterosexuality of the discussion, as his behaviour is a stark contrast from those of Oscar and Angie.

The comedic homosexual foil is often used as a vehicle in assisting the heterosexual protagonist in validating his or her own sexual identity, seen in other films such as, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World and The Perks of Being a Wallflower. It is ultimately Lenny’s presence that leads the two characters to the storage unit where this discussion takes place, and it is Lenny’s identity and familial issues that bring the two characters together at the film’s conclusion.

Although Lenny’s sexuality is never explicitly mentioned in the film, DreamWorks’ application of this stereotypical trope within an animated aquatic world illustrates that this sad cliché of queer representation is so widely accepted that it can now even be used to characterize animals within an animated family picture.

[1] Adams, Carol J., The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc., 2015)