In the Ratatouille scene where Remy and Emile enter an old woman’s house, questions of animal invasion into human spaces are raised. The woman’s reaction is to kill the trespassing rats; a reaction which, in reality, we would be unlikely to query.

Fig. 1

As uncaged rats they represent pests, undesirable to find in one’s home. The human that discovers them in her house reacts hyperbolically – using a large gun to repeatedly shoot at them, the power of the weapon visibly jolting her whole body. This slapstick style action provides comedy; in her attempts to kill the rats she destroys her house, amplifying the exaggeration of her reaction as a desperate, mindless act.

Fig. 2

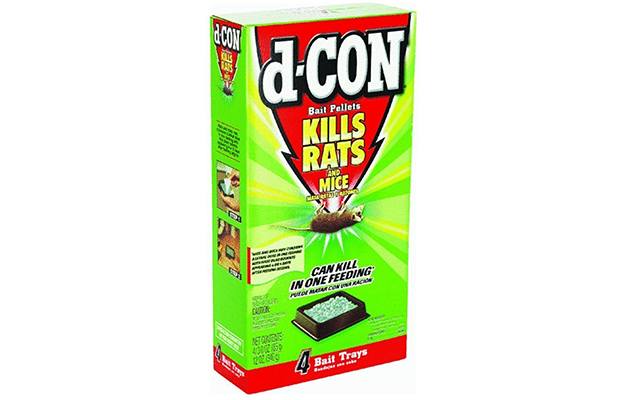

This leads us to reflect on how we would react in a similar situation. When finding pests, such as rats, in our home it is common for humans to suggest to one another the placement of poisons and traps to kill them, without real consideration for the act of ending its life. The scene addresses this issue by making us associate more with the animals on screen than with the human. However, the animals in this scene are anthropomorphised, and Remy is the protagonist of the film. So, although we sympathise with the rats in the scene and hope that they escape, it is questionable whether it makes us reconsider our treatment of rats in real life.

One of the ways the direction of the scene leads us to sympathise with the rats is through the shot-reverse-shot between Remy talking to Emile, and the woman looking at them. We have previously always seen the rats of the film speaking English, but when the camera is behind the woman and we see her perspective, it shows that she can only hear expressive squeaks. We see the woman’s confusion as she sees the rats’ attempt to communicate through noise and gesture.

Fig. 3: We hear squeaks Fig. 4: We hear English

During this, the director chooses to have Remy in focus and the woman in soft focus, whether the camera angles have Remy in the background or the foreground. Despite the change in diction, this secures Remy as the main focus of the shot, helping solidify our sympathy with him rather than with the woman whose house he has entered. This change in perspective, to that of the woman, also shows the ability for humans to unknowingly anthropomorphise animals without meaning to; the woman’s perspective only shows the rat squeaking, but she (and we) see him as ‘talking’ to Emile. It causes the previously manically gun-wielding woman to hesitate before attempting to kill the rats. By considering them as conscious, communicating animals rather than pests, and pausing for a moment to reflect, she encourages the audience to do the same. We assume that it would make a difference if she saw them anthropomorphised as we have seen in the rest of the film, in that she too would want them to live. By only imagining she has seen human qualities in the character rats, her motive to kill them remains the same. Thus, we must ask how simple Disney-style anthropomorphism makes us sympathise with animals we have culturally been encouraged to detest.

Fig. 5 Fig. 6

By not having the woman use any speech in this scene, only gasps and grunts, she is further alienated from the audience. It presents her as more animalistic than the rats who we have previously seen talking and communicating in a human way. Her frantic actions also add to this human-as-animal representation by showing a lack of thought process – a quality we would normally assign to animals. The woman’s reaction – single-handedly destroying her home as a means of policing the boundaries of her human world – confronts the audience with a representation of humans’ culturally intrinsic desire to hate and want to exterminate rats. It questions who is really the pest – the more frightening and dangerous; a position not often presented to contemporary audiences regarding non-traditional, domestic or exotic animals.