In a world where humans are relentlessly attempting to control and train animals, it is intriguing to see this portrayed in reverse in Brad Bird’s, Ratatouille.[1] Remy the rat is depicted as significantly smarter than the human (Linguini), as he teaches him how to cook and navigate his way around a kitchen; whilst Linguini remains predominantly confused and ignorant about the tasks he’s performing.

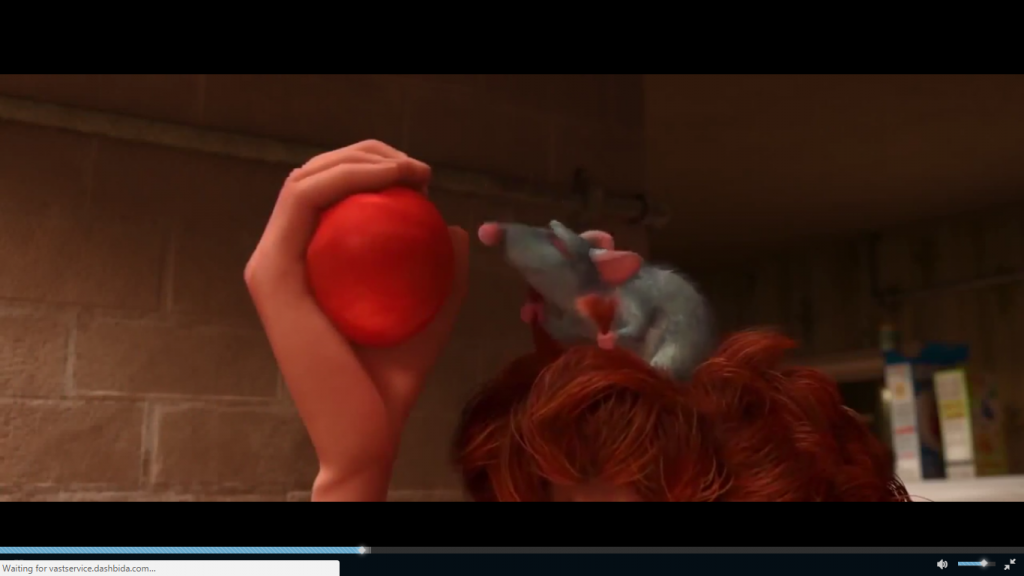

| Remy demonstrating his ability to control Linguini by tugging sections of his hair. |

The foremost presentation of this authority shift from human to animal is during the scene in which Remy realises he can control Linguini by tugging sections of his hair, causing him to mirror his actions. By placing the animal in the position of power instead of the human, this presents the film’s attempt at reworking expectations about superiority and control between them. Linguini is presented as the foolish submissive character, whilst Remy is the intelligent and domineering puppeteer, the polar opposite to the pre-existing representations of humans and animals. Furthermore, Remy’s ability to control is amplified as he is able to not only manipulate Linguini, but he tactfully deceives and outsmarts the other kitchen staff by remaining hidden throughout the film.

This reversal of control also challenges notions of intelligence between humans and animals, as Remy’s capacity to manipulate indicates towards an elevated intellect , whilst Linguini maintains his confused state, ‘how did you DO that?’, consequently revealing his slow mind-set. Remy’s preeminent intellect is further accentuated as he can understand the human language, whilst the humans cannot understand him. This presents Remy’s ability to surpass his own species and instincts in order to appear more human. His anthropomorphism is demonstrated as he stands on his hind legs, using his front legs as arms and smiles. These express clear stereotypical human characteristics that Remy’s bright mind allows him to replicate.

Remy’s superiority is physically demonstrated as Linguini conceals his eyes with a blindfold. The human is therefore entirely submits to the control of the animal, as the scene switches to a montage of Remy guiding him around the kitchen. His role as master is highlighted as Linguini lifts the tomatoes to Remy’s nose to test rather than his own, exaggerating the shift in command. The point of view camera angles also serve to emphasise Remy’s superiority, as the film is either shot from his perspective, or he largely dominates the frame, thus maintaining the primary focus of the audience. This again reverses this concept of control in human and animal relations. Linguini lifting a tomato to Remy’s nose to test, explicitly demonstrating the power switch.

Interestingly, their names also present another inversion of power as the rat has a characteristically human name ‘Remy’. This also alludes to Remy Martin, a leading name in fine wines, emphasising his elevated status and taste; whilst the human has a relatively senseless name, ‘Linguini’ after the pasta ‘linguine’. This brings with it associations of blandness in comparison to the high status of Remy Martin, confusing his sense of identity and de-humanizing him.

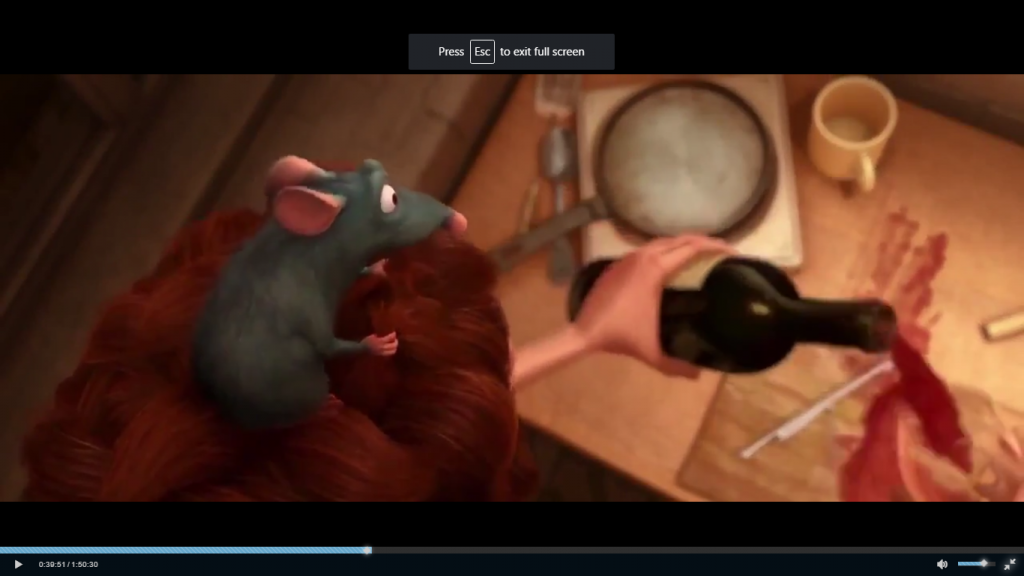

A comic element is also generated through Linguini’s clumsiness as the dominated subject, as he becomes animalized. He squeezes the tomato covering Remy in its residue; he throws a frying pan out of the window and spills copious amounts of red wine. This slapstick humour not only blends with the animated children’s genre, but has connotations with the carnivalesque as hilarity stems from the delight in the grotesque. Exaggeration and hyperbole are integral elements of the grotesque style, therefore, as well as the overdramatic food spillage playing a part in this; the grotesque is also associated with the human body. Linguini becomes animalized through his clumsiness as the audience becomes increasingly aware of his limbs. Appearing as a grotesque puppet with a rat as a master, what should ordinarily be a sickening image of a blindfolded human with no control over their own limbs becomes comical and humorous under the children’s genre. Anthropomorphism combines with animalization as linguini becomes the animal, trying and failing to be trained by his anthropomorphic master, destabilizing expectations about species as Remy is in control.

| Linguini spilling the wine, demonstrating the grotesque carnivalesque. |

The reversal of power is also presented as comic through the playful music paired with the sound effects of Linguini’s ‘involuntary’ exclamations of shock and confusion. The stark juxtaposition between them is highlighted here as Remy silently works, foregrounding his supremacy and intelligence. Further comedy and light heartedness is implied by the warm colour palettesof browns and rouges as they capture the heart-warming nature of a children’s genre, maintaining its stance as a ‘feel-good’ film.

Overall, the comic representation of Remy as the brains and Linguini the brawn retains the moral lesson of not judging others based on appearance, as the assumption of the ‘superior human’ is countered here. Remy subverts all pre-existing expectations about animals as he becomes the anthropomorphic ‘brains’ and Linguini the animalized subservient subject.

Word count: 846.

[1] Ratatouille. Dir. Brad Bird. Buena Vista Pictures. 2007.